“WITHOUT TAP of DRUM”

by James Gettys, Jr., Author – Historian

Chapter One: A Man of Certainty and a Half-Breed

He believes “that everybody agrees with him when he expresses an opinion, which offends me. . . .” Varina’s first impression of Jefferson

Even today this sphinxlike, complex man, with so many virtues and so many faults, is not really understood by modern historians. Clement Eaton

Varina Howell Davis was a nineteenth century woman prepared for the twentieth century, while Jefferson Davis was a man of the nineteenth century. She was highly intelligent, and had a superior education, but was challenged as a young girl by insecurities resulting from her father’s bankruptcy and inability to support his family at a level commensurate with its social standing. During her adult life she sought and valued security. She seemed fearless, and her family’s adversities taught her to face obstacles with resilience. Her social skills were polished, and she conversed meaningfully with wealthy and politically powerful men, no mean thing for an antebellum female. Perhaps most importantly, she understood the course of the war, and before its outbreak, anticipated defeat. Her concerns were based on her evaluation of the power differential between the Confederacy and the United States. One side, a developing industrial power with standard railroad gauge, the other with a nascent industrial base and multiple railroad gauges. She loved Jefferson Davis, but their relationship was frequently not harmonious, largely because his narcissism smothered her personality. He was not always faithful and ignored her ideas.[2]

Varina’s ancestor, William Howell, knew George Washington, was a Revolutionary War hero and served four terms Jefferson Davis Journey as governor of New Jersey. Margaret Kempe Howell, her mother, was from a slaveholding family. Varina called herself a half-breed and lived in both sections, spending her last sixteen years in New York. She mentioned in an interview that she “observed that everyone was a ‘half-breed’ of one kind or another and they were smarter than so-called full bloods.” Varina seemed to follow the Aristotelian Golden Mean, not just in her lineage, but in her politics, her finances, her friendships and in her attitudes toward race. She opposed abolition but was not a strong secessionist. She was pro-slavery but also pro-Union. She endorsed the Confederacy but was realistic about an unlikely Confederate victory. She wrote that she was not like Jefferson and his radical friends because she believed in compromise. These ideas were in juxtaposition to the unbending dogmatism of Jefferson Davis who always knew his was the correct way.

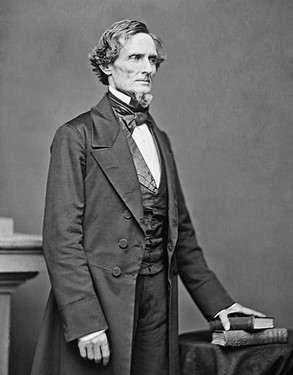

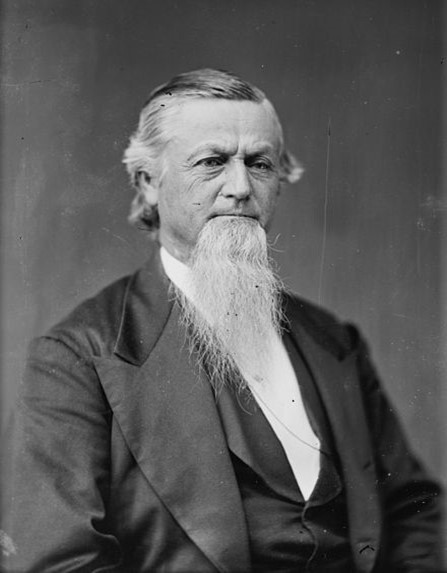

Jefferson Finis Davis – Courtesy of Wikipedia

Joseph Davis, Jefferson’s elder brother, threw himself into creating his huge plantation empire, working alongside his slaves, in the manner of Thomas Supten. Joseph had several plantations covering thousands of acres located in a large bend of the Mississippi known as Davis’ Bend. He saw that Jefferson was well educated and able to live as a privileged aristocrat. Jefferson graduated from West Point, served under Zackary Taylor, and married, contrary to Taylor’s wishes, his daughter Sarah Knox Taylor. She was the love of Jefferson’s life but died three months after their marriage. After Sarah’s death, Jefferson lived in seclusion on Briarfield, a 900-acre plantation, owned by Joseph. In December 1843 Joseph Davis, possibly playing matchmaker, invited seventeen-year-old Varina Howell to Hurricane, his 5,000-acre plantation at Davis’ Bend. Varina’s tutor, George Winchester, took her to Diamond Place, owned by Florida McCaleb, Joseph’s married daughter. Varina attended Joseph’s Christmas party at Hurricane where she met and fell in love with Jefferson. Varina wrote her mother after she first met Jefferson. The thirty-four year old widower made a strong impression on the seventeen-year-old Varina who wrote her mother that he was “a remarkable kind of man, but of uncertain temper, and has a way of taking for granted that everybody agrees with him when he expresses an opinion, which offends me. . . .” In The Long Surrender, Burke Davis contended, “the young, inexperienced Mississippi country girl had accurately plumbed the personality that was to baffle so many of Jefferson Davis’ Confederate cohorts and historians of later years.”[3]

Jefferson seemed concerned about Varina’s health, perhaps from a hypersensitivity because of Sarah Taylor Davis’ short life. Ironically, in Embattled Rebel James M. McPherson asserted that Davis had more chronic maladies than any other chief executive in American history. Burke Davis wrote that Jefferson Davis was “pale, feeble, and distraught. He had become an incurable insomniac . . .” by 1865. Varina and Jefferson were engaged in February 1844 and married on February 26, 1845. Their wedding trip included a visit to Jefferson’s first wife’s grave. Clement Eaton, in Jefferson Davis, wondered “what Varina must have thought of such a pilgrimage on her honeymoon.” They had different ideas about gender. Jefferson anticipated that Varina would always defer to him. She had her own mind. Her mother, a lover of books, bequeathed this passion to Varina. George Winchester, a native of Salem, Massachusetts with a Yale degree, tutored Varina in Latin and classics for twelve years. She attended Madame Deborah Grelaud’s Seminary in Philadelphia. At Grelaud’s Seminary she was exposed to abolition and early women’s rights activities. Jefferson and Varina had had serious conflicts. Briarfield, Jefferson Davis’ plantation, was owned by Joseph Davis. This arrangement bothered Varina because if Jefferson died, she would be homeless and unable to care for her children. She argued with Jefferson, but as with every other issue, Jefferson brooked no disagreements. They were separated when Jefferson was serving in the army and in Washington. In Jefferson Davis, Confederate President, Herman Hattaway and Richard Beringer wrote that when Jefferson was in Washington his relationship with Varina was “marred by acutely strained relations between him and Varina.” Their arguments over Briarfield made them, to some degree, estranged. Divorce was not an alternative given gender relations in the 1840s, and Varina’s inability to support her children outside marriage. Jefferson did bestow expensive gifts on Varina and gave generously to her family members who constantly needed assistance. Davis was pictured as a loving father who played on the floor with his children. Allen Tate, poet essayist and Vanderbilt Agrarian, wrote Jefferson Davis, His Rise and Fall. Tate quoted a letter from Jefferson to Varina addressed to “Winnie” from “Banny,” an unexpected signature from a man who seemed so officious. Virginia Caroline “Jennie” Clay noted that Davis was “cold and haughty,” in public, but in private he was “informal and frank.” Clement Eaton saw the significant contrasts between the personalities of Jefferson and Varina. He concluded that “conflict was dissipated by Jefferson’s agreeable personality with the family,” in a milieu that favored male authority. Varina eventually followed her mother’s advice to accept Jefferson’s will, the only alternative, given Davis’ inflexibility. Eaton suggests Jefferson’s sisters, accepting the southern standard of female subordination, were deferential to him, reinforcing his narcissism.[4]

Generally, historians have not treated Davis well, and he suffers from those who compare him with Abraham Lincoln. James McPherson pointed out that “Lincoln’s side won the war. But that fact does not necessarily mean that Davis was responsible for losing it.” The power relationship between North and South was enormously asymmetrical. The North was an emerging industrial and transportation power while the South consisted of a group of states dependent on chattel slave labor. “They confronted different challenges with different resources and personnel.” McPherson found Davis came “off better than some of his fellow Confederates of large ego and small talents who were among his chief critics.” The negative descriptions of Davis’ personality come from persons “who often had self-serving motives for their hostility.” He did not tell others what they wanted to hear, and he did not suffer fools gladly. One Georgia Congressman changed his mind about Davis after he got to know him. He wrote his wife that Davis was not the

Image of First Lady Varina Davis – Courtesy of Wikipedia

puffed-up man he was supposed to be. “‘He was polite, attentive, and communicative to me as I could wish. He listened patiently to all I said and when he differed with me, he would give his reasons for it.’” Davis’ “‘enemies have done him great injustice.’”[5]

In 1850 Jefferson entered the Senate, and Varina’s social skills, intellect and organizational talents boosted his career. Varina was a highly successful hostess in Washington. “A brilliant conversationalist, she enjoyed talking with prominent political leaders, who paid great deference to her.” Varina had sixty-two Senators and 234 Congressmen to dinner at least once every year. Every Tuesday afternoon she hosted a reception where she conversed with the political elite about the latest literature. She was appreciated by those, like John C. Calhoun, Charles Ingersoll and James Buchanan, who had “advanced views on the parity of the sexes and pioneered this behavior, speaking to women as their equals and listening in return, a quality that Varina Davis especially appreciated.”[6] Her attitude and attention were always bipartisan. Her social skills smoothed out disagreements, an especially important talent for the wife of Jefferson Davis. She expressed strong opinions to Jefferson, but he was “too strong-willed and opinionated to be swayed by petticoat influences.” Secretary of State Judah P. Benjamin became a close friend because of his love of books and enlightened views on gender. His serenity settled Varina in times of stress.[7]

Varina absorbed the Washington etiquette established by Dolly Madison and she quickly assembled a wardrobe in the latest French fashions. Elizabeth Keckley, a free person of color, was Varina’s seamstress. When Varina departed, Keckley was employed by Mary Todd Lincoln. Varina was one of the first women in Washington to wear hoops. As First Lady of the Confederacy in Richmond, she found an absence of Washington’s rules of etiquette and the dominance of a culture enamored with the past. First Families of Virginia still mattered and Martha Pierce Stanard, the doyen at the time, hosted groups whose discussions were less than intellectually stimulating. Stanard informed newcomers that she had not read a book since she became an adult. Varina worked assiduously in support of Jefferson and even chaperoned young people on excursions down the James River.[8]

As the end of the war approached, trusted slaves ran away from Richmond to the Union lines. James Dennison and his wife Betsey, both household slaves for the Davis family for years, ran away. Betsey had been Varina’s maid, and she took eighty dollars in gold and $2,000 in paper money with her. Shortly after Betsey and James left, a fire broke out in the Davis’ basement, leading to confusion. Henry, a butler hired some few months before, was seen no more. Ellen Barnes, a biracial enslaved woman, took over Betsey’s duties. Ellen was in her mid-twenties, had been a servant of a Richmond druggist and was abandoned by her husband when he fled north. Ellen was illiterate but very observant and appeared “faithful.” She was present when Davis was captured. Some witnesses said Ellen was disguised and assisted Jefferson in his foiled escape. After the war she expressed “great affection” for Varina but that she would “‘rather be free, much rather.’” A picture was made of Ellen holding “Winnie,” Varina’s last baby, named Varina Howell Davis, born on June 27, 1864, and known as the “daughter of the Confederacy.” W. C. Davis called Ellen a nurse for the Davis children, a position of trust. Varina hired a white woman, Mary O’Melia, to run her house. William Jackson, Davis’ slave coachman, ran away to the Union lines. He was taken to Washington where Secretary of War Edward Stanton questioned him. This incident received widespread coverage in the northern press, portraying Varina and Jefferson negatively. Varina hired James H. Jones, a free African American, to work for her as a coachman. Jones, like Ellen, faithfully served Jefferson and Varina until they were captured. Jefferson and Varina were pictured as terrible slave owners in the northern press, but southerners believed they were kind and benevolent owners. African American slaves who knew Jefferson and Varina give varied evaluations of them as owners. A few slaves seemed positive about the Davises as owners after the war. James Lucas, a slave, evaluated Jefferson and Varina with the statement, “‘he wuz good but she was better.’”[9]

Neither Jefferson nor Varina agreed with the scientific racism of the 1850s. Some researchers and scientists advocated polygenism, that there were multiple types of humans created but that African Americans were a separate and inferior type of humanoid. Joan E. Cashin never found an instance of Varina’s using the word “nigger.” She always used “Negro.” While one can only speculate how Christians could have owned humans, it is evident the Davises were not harsh owners, but were irrevocably attached to chattel slavery. Davis supported the effort to arm slaves. In the acerbic debate over this issue Robert Mercer Talliaferro Hunter broke with Davis and joined those who argued that the South was fighting a war to keep slavery the cause of the war.[10]

Varina also understood the realities of the Civil War and understood that the cause was doomed. As early as 1862 she began to worry about her future and that of her children. In the spring of 1865, she became bitter and depressed. By the end of March many on both sides thought Davis should surrender and several people blamed his reluctance to surrender on Varina’s influence. But that decision, as all major decisions in their lives, was made by Jefferson. When Jefferson told Varina she should leave Richmond, she hastily gave away household furniture or just left it in place. She packed away “about two thousand in gold, a revolver, and some books.” They managed to sell property they could not move and had a check for $28,550 which Jefferson forgot to cash. Since $60.00 in Confederate money was worth about one dollar in gold, they would receive about $450.00. Jefferson sent the check with an aide to the Bank of Richmond which was closed. The check was non-negotiable. By the time he reached Danville, Davis had about five dollars in gold.[11]

Footnotes – Chapter One:

[1] C. Vann Woodward, ed., Mary Chesnut’s Civil War (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1988), 773

[2] Joan E. Cashin, First Lady of the Confederacy: Varina Davis’ Civil War (Cambridge: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2006), 33–36.

[3] Cashin, First Lady, 35. Burke Davis, The Long Surrender (New York: Random House, 1985), 10.

[4] Cashin. First Lady, 33-36, 44, 97, 253, 285, 292. Eaton, Jefferson Davis, 23- 25, 28, 31, 32. James M. McPherson, Embattled Rebel: Jefferson Davis as Commander in Chief (New York: The Penguin Press, 2014), 7-8. McPherson noted Davis’ malaria, corneal ulceration of his left eye possibly causing neuralgia with its extreme pain, nausea and headaches, “Dyspepsia” (ulcers or acid reflux), lack of appetite causing the gaunt appearance, bronchial problems, insomnia, and boils. He often had to work from home and once was out of his office for a month. McPherson speculates that Davis suffered from stress and that there could have been psychosomatic problems. He also considered the possibility that Davis’ “perceived irritability and peevishness” was a consequence of his illnesses. Burke Davis, The Long Surrender, 7-8, 10. Allen Tate, Jefferson Davis: His Rise and Fall (Nashville: J. S. Sanders & Co., 1929, 1998 edition), 278. Madame Grelaud, an exile from Saint-Domingue during the Haitian Revolution, operated her Seminary or French School as it was called, in Philadelphia between 1809 and 1849. Herman Hattaway and Richard E. Beringer, Jefferson Davis, Confederate President, (Lawrence Kansas: University of Kansas, 2002), 10.

[5] McPherson, Embattled Rebel, 4-7.

[6] Cashin, First Lady, 43, 65. Eaton, Jefferson Davis, 26.

[7] Cashin, First Lady, 122-123. Clement Eaton, Jefferson Davis, 26, 30. Hattaway and Beringer, Jefferson Davis, 30.

[8] Cashin, First Lady, 66, 102, 111. Tate, Rise and Fall, 214-219. Tate noted Thursday was the day for her legislative receptions in Richmond.

[9] Cashin, First Lady, 38, 40, 126, 143, 145-146, 148-149, 164-165, 246. William C. Davis, An Honorable Defeat: The Last Days of the Confederate Government, (New York: Harcourt, Inc., 2001), 302. The American Civil War Museum https://issuu.com/acwmuseum/docs/acwm_magazine_fall_2019/s/16394285, accessed March 11, 2024, states it is not possible to know if Ellen Barnes McGinnis were slave or free.

[10] George Robins Gliddon, Louis Agassiz and Josiah Clark Knott, Types of Mankind (Scholar’s Choice, 2015 reprint of the 1854 original). Cashin, 62, 63, 97, 98. Tate, Rise and Fall, 262. Hunter, a national politician before the war, served as Secretary of State (1861-62 and senator (1862-65).

[11] Cashin, First Lady, 133, 150, 154, 155, 157. James C. Clark, Last Train South: The Flight of the Confederate Government from Richmond (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, Inc., 1984) 11. Burke Davis, Long Surrender, 27, 29, 52. Davis, Honorable Defeat, 207.

________________

Chapter Two: Varina and the Gold Train

Abbeville: “a more fitting setting for a May Day festival than for the scene of the disruption of a government.” Burton Harrison

In her camp near Washington, “the ground felt very hard that night as I lay looking into the gloom and unable to pierce it even by conjectures.” Varina Davis, May 2, 1865

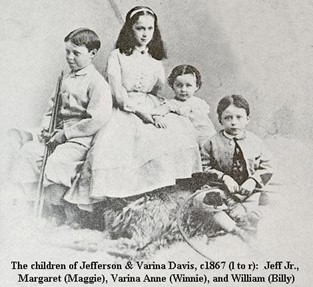

The children of Jefferson and Varina Davis – Courtesy of Find A Grave

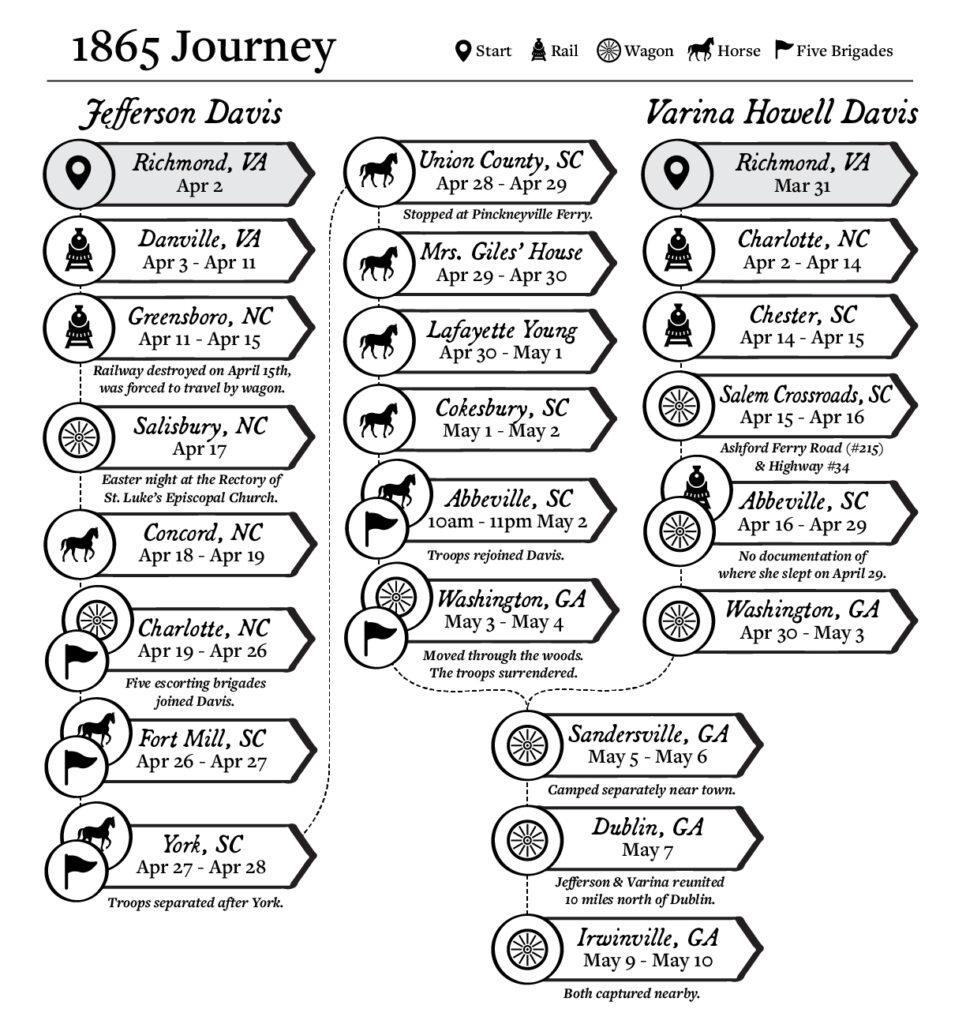

Varina Howell Davis left Richmond at around 10:00 p. m. on March 31, three days before the Confederate capitol was evacuated, bound for Charlotte. With Varina were daughters of Treasury Secretary George Trenholm, Burton N. Harrison, Jefferson Davis’ personal secretary, and James Morris Morgan, a naval officer assigned by Secretary of the Navy Stephen Russell Mallory, as escort for Trenholm’s daughters. Morgan was engaged to Betty Trenholm, and they later married. Three servants were also aboard: Ellen Barnes, her maid, a nurse, and Varina’s coachman, James H. Jones. Davis had purchased carriage horses for Varina in Western Virginia, but Varina sold them in Richmond because forage became too expensive. Some gentlemen purchased them for $13,000 in Confederate money (about $260 in gold) and returned them to the President’s wife. These carriage horses were seized when Davis was captured. Family members who accompanied Varina were Margaret “Maggie” Graham Howell, Varina’s sister, and Varina’s children: Margaret Howell Davis “Maggie” (10, 1855-1909), Jefferson Finis Davis, Jr., “Jeff, Jr,” (8, 1857-1878), Joseph E. Davis, “Joe” (5, 1859-1864), William Howell Davis, “Billy”, (3, 1861-1872) and Varina Anne Davis (“Winnie” “The Daughter of the Confederacy,” 1864-1898), who was less than a year old during the flight. Morgan found the passenger car filthy, worn out and “very suggestive of the vermin with which it afterwards proved to be infested.” The ruined interior had weathered paint, peeling varnish and smoky oil lamps with “soiled brown plush seats which were infested with fleas.” Mary Chesnut declared that soldiers were “packed like sardines in dirty RR cars. Which cars are usually floating inch deep in liquid tobacco juice.”[12]

Mrs. Mary Boykin Chesnut of Camden, S.C. – Image courtesy of Wikipedia

In February 1864 Varina, riding in her carriage on the streets of Richmond, saw an African American man beating a young boy beside a Richmond Street. She rescued the five-year-old-boy and took him to her home. His father had escaped to the North and his mother, a free African American, had died. He said his name was James “Jim” Limber. He was free because of his mother’s status. Jefferson Davis secured his freedom papers but was unable to find a member of his family. On February 16 Mary Boykin Chesnut “saw in Mrs. Howell’s room the little negro Mrs. Davis rescued from his brutal negro guardian. The child is an orphan. He was dressed up in little Joe’s clothes and happy as a lord. He was very anxious to show me his wounds and bruises, but I fled. There are some things in life too sickening, and cruelty is one of them.” James remained in the Davis household, seemingly a playmate of the Davis children. The boys, Joe and Jeff, Jr. belonged to a neighborhood group known as the Hill Cats, and Jim joined the gang. When Varina fled Richmond, Jim went along with the family until they were captured. In Savannah a captor ordered that James leave the family. Varina sent him to a Radical Republican she had known before the war, Brigadier General Rufus Saxon, stationed in Beaufort, South Carolina. [13]

Thomas Conolly, an eccentric Irish Member of Parliament, and Confederate sympathizer, rode a train to Greensboro on March 6, 1865, and experienced conditions similar to those of Varina. It was “a rough journey in filthy carriages. . . .” He found the “whole place full of soldiers in all manner of garb, prisoners returning on parole & all the strays and waifs of war.” When he left Greensboro, the cars were filled “with motley troops armed & covered with picturesque crowds camping on top and rolling themselves in their large blankets with nothing but beards & sloughhat and rifle protruding, etc.” Everyone and everything was “covered & splattered with red mud.” The slouch hat was first worn by soldiers in the English Civil War during the 1640s and had gained popularity all over the British Empire. It had a wide brim and the front and back sloped downward to shed water.[14]

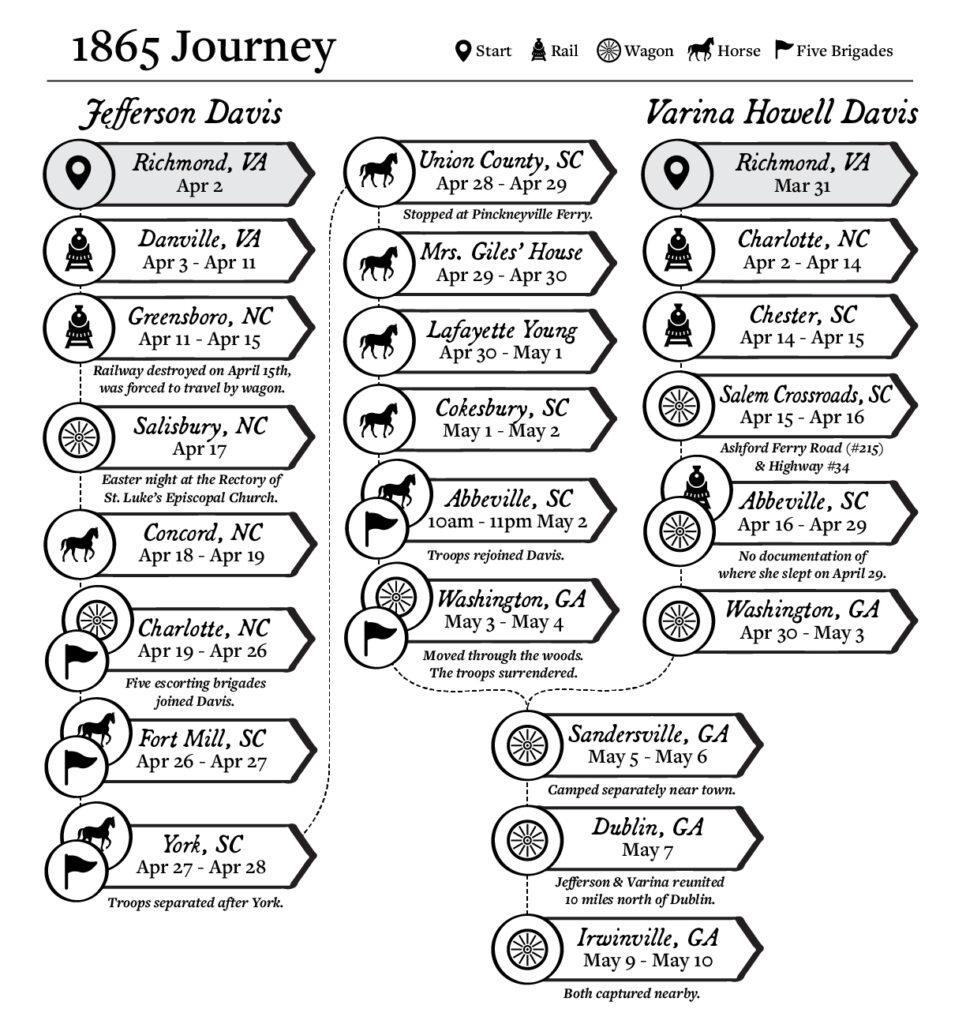

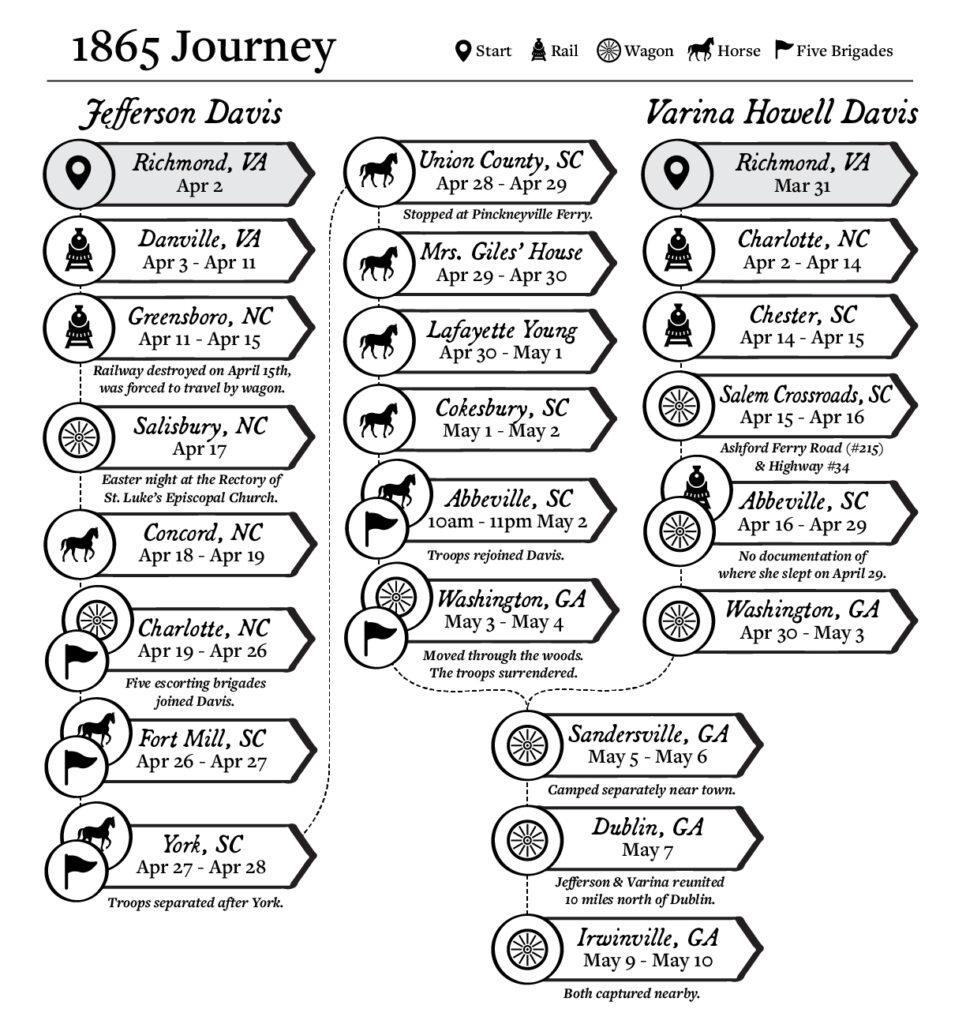

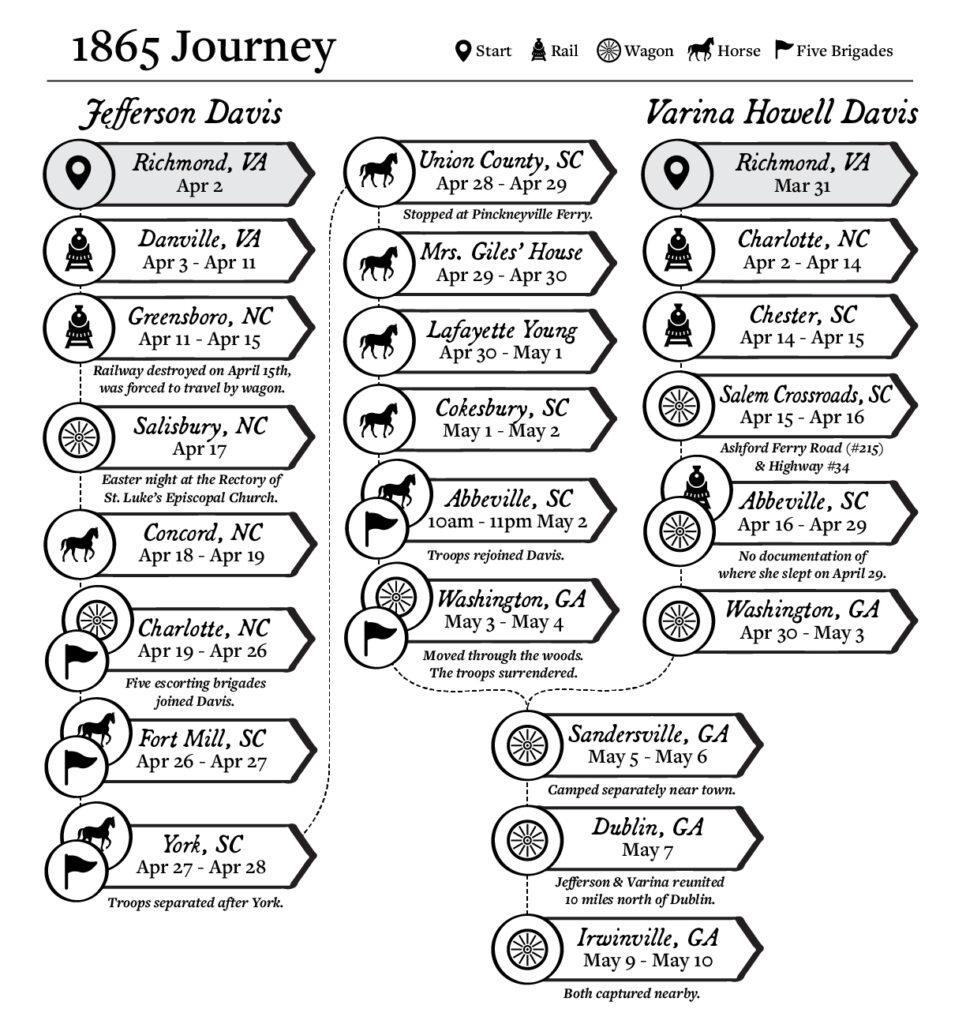

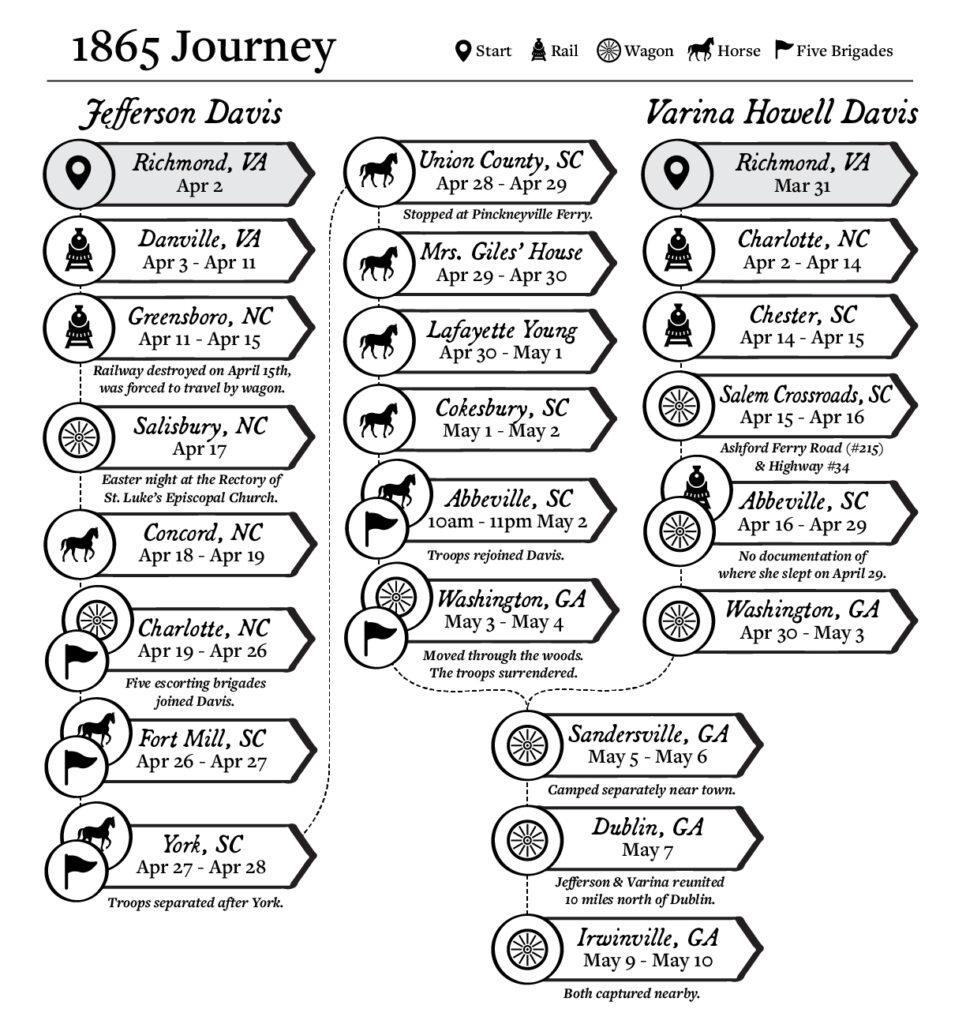

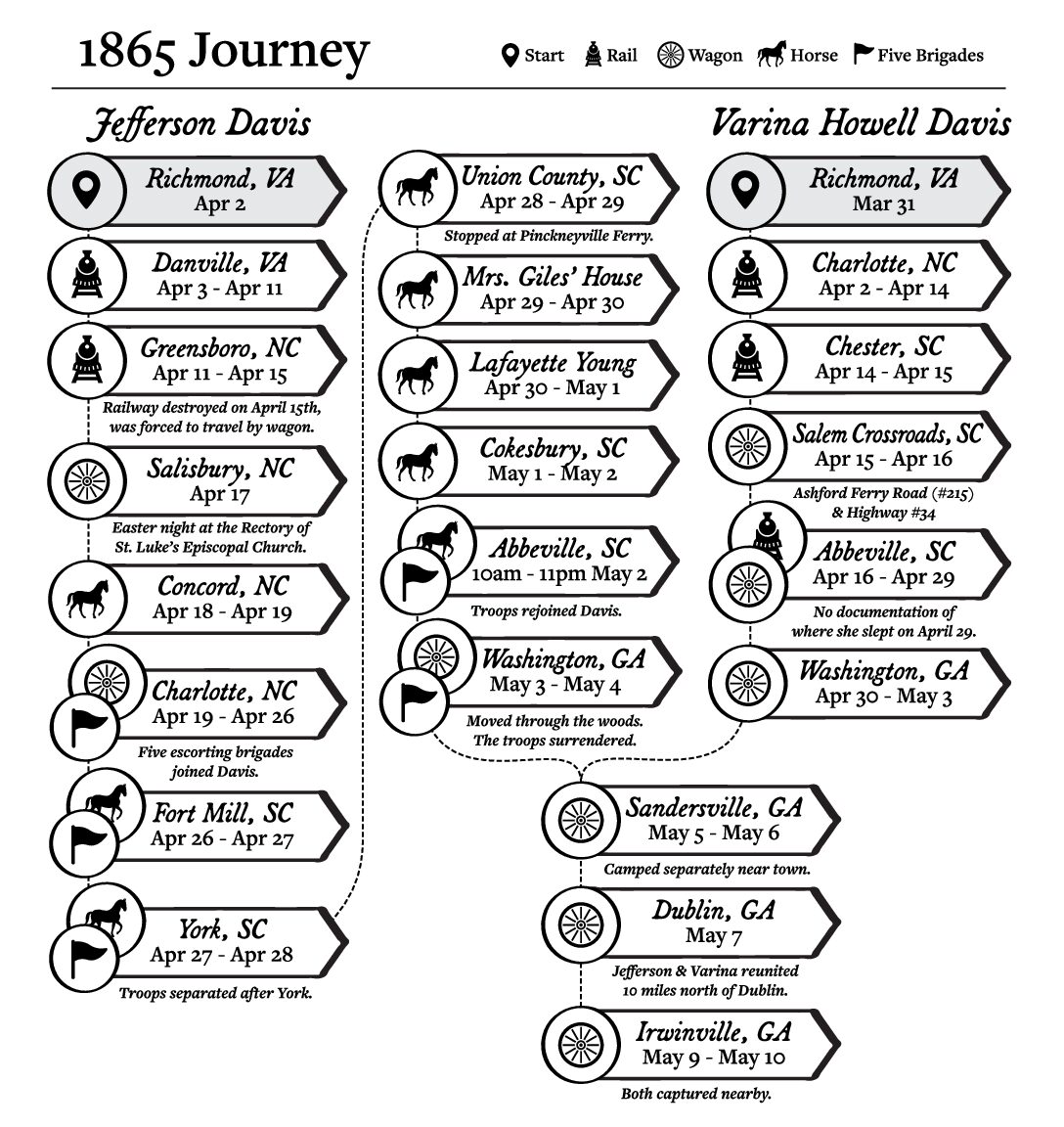

Journey of Jefferson and Varina Davis

Varina’s dilapidated locomotive “balked” after twelve miles. Engineers spent the night resuscitating the engine and, in the morning, it climbed the slight “up-grade” that had stymied it. Burton Harrison spent $100.00 in Confederate money to purchase milk and crackers for the children. Varina endured such conditions until she reached Charlotte, a three-day trip that steam engines after the war made in six or seven hours. Varina remained in the Queen City until April 13th, the day after the Army of Northern Virginia surrendered. Jefferson Davis, along with government personnel who fled Richmond, established offices in Danville. Davis stayed at the Danville home of William T. Sutherlin from April 3 through April 10. Jane Patrick Sutherlin, hostess for Davis and his cabinet in Danville, believed Davis seemed to have rapid mood swings between optimism and resignation and ate little or nothing. According to Danville accounts, the Sutherlin home, “the last capitol of the Confederacy”, was where “Davis assembled his cabinet for the last official conference and signed the last documents of the Confederacy before the surrender of Gen. Lee.” Robert E. Lee signed the armistice on April 9. Davis was informed of the armistice on April 10, was shocked, packed quickly and went fifty miles south to Greensboro. The government papers, so recently unpacked in Danville, were repacked in boxes. John Cabel Breckinridge, Secretary of War, had these papers, essential for government, stored in Charlotte so that the history of the Confederacy could be written. Most Confederate

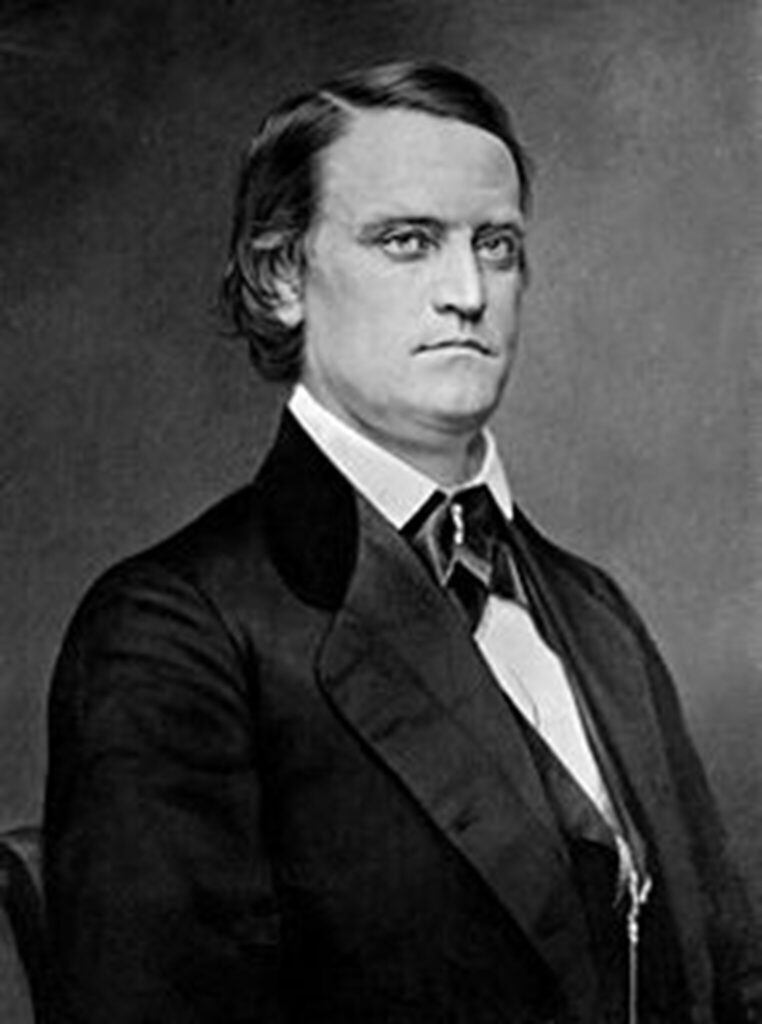

John C. Breckinridge, CSA Sec. of War – Courtesy of Wikipedia

bureaucrats went home from Richmond or Danville. After the boxes left Danville there was no functioning Confederate government. On April 12th Joseph Eggleston Johnston and Breckenridge agreed that the “Southern Confederacy was overthrown.” Varina’s position in Charlotte was tenuous. Morgan remembered, “the inhabitants, however, did not rush forward to offer the lady in distress hospitality as they might have done a year or two before misfortune had overtaken her.” News of Varina’s arrival spread quickly in Charlotte, “which was thronged with stragglers and deserters – conscripts – the very scum of the army, and a mob of these wretches gathered around the car in which she sat. The wretches reviled her in most shocking language.” Morgan and Harrison closed the Pullman’s windows so Varina could not hear the language. “We two men were helpless to protect them from the epithets of a crowd of some seventy-five or a hundred blackguards. . . .” Varina had been thrust “in a forlorn position, as nobody wished to shelter her for fear that the Union troops would destroy their homes if they did. Every road through the country was infested by deserters who would have given her scant consideration if they wanted anything she possessed. . . .”[15]

Harrison found shelter for Varina and her family with Abram and Barbara Weill. Harrison described Weill as an “Israelite” merchant whose house stood at 237 South Tryon Street, where the Fed Ex building was later built. The United Daughters of the Confederacy erected a monument at this location in 1948. It was removed in 2020.[16]

On April 2 William Harwar Parker received a wire from Stephen Mallory requesting that Parker be at the Danville Depot in Richmond at 6:00 p.m. Parker was assigned the duty of transporting Confederate gold and silver from

William H. Parker – Courtesy of Wikipedia

Richmond to the Charlotte Mint. For the last three years of the war Parker ran the naval school for Confederate midshipmen in a Confederate naval steamer originally named the Yorktown. It was rechristened the Patrick Henry and anchored below Drewry’s Bluffs, on the James River at Richmond. Students lived in cottages until the last year of the war, when the Patrick Henry was towed upriver to Rocketts where the students lived on board. The bilge water became fouled, some midshipmen were hospitalized, and others were moved to a tobacco factory in Richmond. Parker commanded from sixty to a hundred midshipmen from the Confederate Naval Academy. Numbers declined as time passed. Charles Iverson Graves, of the Treasury Department, joined Parker along with several clerks and their families.[17]

The midshipmen left their quarters at 4:00 p. m. on May 2. They marched to the Danville Depot, entrained, and saw the wooden containers holding gold and silver. The amount was casually estimated at about a half million dollars, and included Mexican silver dollars, American double eagles, ingots, nuggets, silver bricks, and a chest of jewels donated by women for a warship. The Midshipmen quickly dubbed these containers “The Things.” Parker also had a company of uniformed men from the Naval Yard. Most of these men were from Portsmouth, Virginia, but few had used weapons. In Danville Clerk Micajah H. Clark, after several allocations, placed a value of $327,022.90 on the Confederate treasury fund. This was substantially less than the casual estimate when the train left Richmond. The difference between the casual estimate and the more careful estimates in Danville resulted in “wild and misleading rumors” that Davis took millions in gold and silver. Davis and advisers obtained $35,000 for their expenses and $39,000 to pay Joseph E. Johnston’s army. On April 10 Parker and his men arrived in Charlotte where the gold and silver were deposited in the Charlotte Mint, and the “midshipmen feasted at the leading hotels.” As conditions deteriorated, Parker realized he had to move the specie. Union forces had destroyed telegraph lines, leaving Parker bereft of communication with superiors. Fearful of Major General George Stoneman’s cutting telegraph lines and destroying bridges to the west and William Tecumseh Sherman’s massive army near Greensboro, Parker took it upon himself to move the specie to Macon, Georgia, presumably a safe location. He requisitioned supplies and prepared to board the train to Chester. He had specie, government papers, treasury clerks with their wives and a thirty-man slave work force. Before leaving Charlotte, Parker invited Varina and her family to join the treasure train. She demurred, but “I rather pressed her on the point as I feared she would be captured, and I could not bear the idea of that.” Varina wrote that since “there seemed to be a panic imminent, I decided to go with my children and servants, on the extra train provided for the treasure, which could only run as far as Chester, as the road was broken.” Parker’s cargo included up to $450,000 in specie from private banks in Richmond. The Confederate specie was packed in “The Things:” wooden boxes of gold, and small wooden kegs containing silver. Parker never saw the gold and silver, but kept his eyes focused on “The Things.”[18]

Parker’s entourage left Charlotte bound for Chester on April 14, 1865. The train was slowed because it was “heavily loaded and crowded with passengers – even the roofs and platform steps” were occupied. This was a hint of the impact on transportation lines and local communities when tens of thousands of Confederate veterans and deserters were homeward bound. It was inevitable that these waves of former soldiers without sustenance would resort to pillaging.

Lieutenant General Joseph Wheeler’s Confederate cavalrymen were notorious marauders, although soldiers from any command without food or money had to find subsistence. In 1865 men who “represented themselves as Wheeler’s Cavalry, were now plundering the country, impressing mules and horses” around Chester, South Carolina. Eugenia C. Babcock’s grandfather “had a beautiful saddle horse to which he was much attached.” Her grandmother fed the soldiers, and the same men stole the prized horse. When Wheeler’s men came through Chester, they “helped themselves to the commissary stores packed away in the various warehouses.” To be fair to Wheeler’s men, Babcock reported that commissary stores were opened, and citizens took what they wanted. Girls “went up there and got their aprons full of sugar; everything was in a demoralized condition.” About twenty miles away from Chester at Steele’s Crossing, where the Lower Lands Ford Road crossed the Saluda Road, Mattie Steele was proactive. When word came that Federals were burning the nearby railroad bridge over the Catawba River, she sent wagons of possessions to the mountains. She also wrapped jewelry and three gold watches in her riding skirt and buried it in the barn. “She put on three of her best dresses and sat for three days upon her trunk containing clothing and valuables.” Federal cavalry never came but many suffered from “the depredations of Wheeler’s men.” Mattie’s father had five valuable horses and mules. “Miss Mattie seized a pistol, in the use of which she was an expert, and ran to the barn. The soldiers approached to get the horses but found a brave girl in the stable door with a cocked repeater in her hand, and, as it was horse flesh and not lead they were looking for, they concluded; ‘Discretion was the better part of valor’ and departed.” Matilda Boyd Gettys lived a few miles from Steele’s Crossing near the Chester County boundary line. She lost her husband and a son to the Civil War and by the spring of 1865 found herself a widow with ten children between the ages of fifteen and two. Foraging veterans stripped her of most of her food including chickens, hogs, and cattle. She hid her two youngest children under the barn. Later another marauding group took what was left, then went after her mule. She stood in the barn door with an old musket pointed at them and said, “One of you may get this mule, but the other one will be dead.” She survived on Irish potatoes and gifts from neighbors. With the mule she could produce another crop. The old musket remains in her family. Caroline Jenney contended that, “Confederates recognized that plenty of less-than-desirable characters had filled the ranks of their armies. And now that they had been set loose from an formal military control, their outrages might know no bounds. . . .” Bushwhackers, deserters, and skulkers perpetrated crimes against Confederate citizens.[19]

Union General William Tecumseh Sherman – Courtesy of Wikipedia

After Sherman burned bridges in the midlands of South Carolina, Chester became a major link in the Confederate logistical system. When Stoneman’s forces burned the railroad bridge over the Catawba on April 19, 1865, a cornucopia of food and supplies backed up in Chester. This bonanza attracted former soldiers as well as many locals who were destitute or simply unable to resist the largess.

When the telegraph gave notice of arriving soldiers, “men and women were seen running in the streets,” preparing assistance. Tables were in a shed near the southern depot “on which the ladies were to place the tempting viands.” A committee found rooms for sick and wounded men. The men with Parker and Varina’s party were well fed in Chester, but this town was at the end of the line when the bridge over the Catawba burned. Mary Boykin Chesnut was a refugee in Chester at 126 Main Street. Abraham Henry DaVega, who owned the building, had his dentist office on the first floor and his living space on the second floor. Mary occupied rooms on the third floor. Soon after arriving, Mary Chesnut was told a raid was imminent in Chester. She asked, “Why fly? They are everywhere, these Yankees – like red ants – like the locusts and frogs which were the plagues of Egypt.” Mary pointed out that there was no army to assist the citizens of Chester. “Plenty of officers – no men.” She wrote that the stream westward never ceased. “Lee’s army must be melting like a Scotch mist.”[20]

Old Chester Hill’s Hotel where Mary Boykin Chesnut reportedly lodged while in Chester, S.C. – Courtesy of Winthrop University’s Pettus Archives, 2024

Mary Chesnut had spent years in Richmond with her husband, James C. Chesnut, a Brigadier General, and aide-de-camp to Jefferson Davis. When Varina arrived in Chester early in the morning of April 14th, James Chesnut began collecting transportation and supplies for her. He and Mary were obligated to do whatever possible for Varina because she and Jefferson were so kind during “their days of power” in Richmond. Mary Chesnut went down to the cars to receive Varina and noted that “lovely little Piecake, the baby, came, too.” The family called her “Winnie.” Mary went to the depot and ate dinner prepared by Chester women. Mary wrote, “I went down with her. She left about five o’clock.” Mary found some residents “so base as to be afraid to befriend Mrs. Davis” because of the presence of “Yankees” who “might take vengeance on them for it.” Mary wrote that her heart was like lead but that Mrs. Davis was “as calm and smiling as ever.” One member of her staff did not rise when Varina entered the room and Mary commented, “could ill manners go further!”[21]

During the afternoon of April 15, the specie was transferred to a wagon train. James Chesnut had secured a large ambulance and one or two wagons for luggage. These vehicles transported Varina, her servants, her sister Maggie Howell, and the children. Men walked, but women rode in the wagons. Thirty laborers managed the wagons and cargo, made camps, cooked, and performed other labor. Varina had close ties to two of the midshipmen: her brother Jefferson Howell and Jefferson Davis’ grandnephew. Varina recalled it was after dark before she was able to follow the treasure train. She was a determined woman who must have been terrified but showed a façade indicative of being in complete control. Varina probably thought often during the war about this end game. Mrs. Benjamin Huger recalled that a year before the war, Varina told her, “‘The South will secede if Lincoln is made president. They will make Mr. Davis president of the whole southern side. And the whole thing is bound to be a failure. So, her worst enemies must allow her the gift of prophecy.’”[22]

One advantage Parker enjoyed in South Carolina was its system of road signs. Major roads had milestones to guide travelers. Byroads and crossroads had wooden signs. Kinloch Falconer, a member of Joseph E. Johnston’s staff, rode home to Bridgeville, Mississippi between May 4th, and June 3rd, 1865. In South Carolina “it is almost impossible to lose one’s way.”[23]

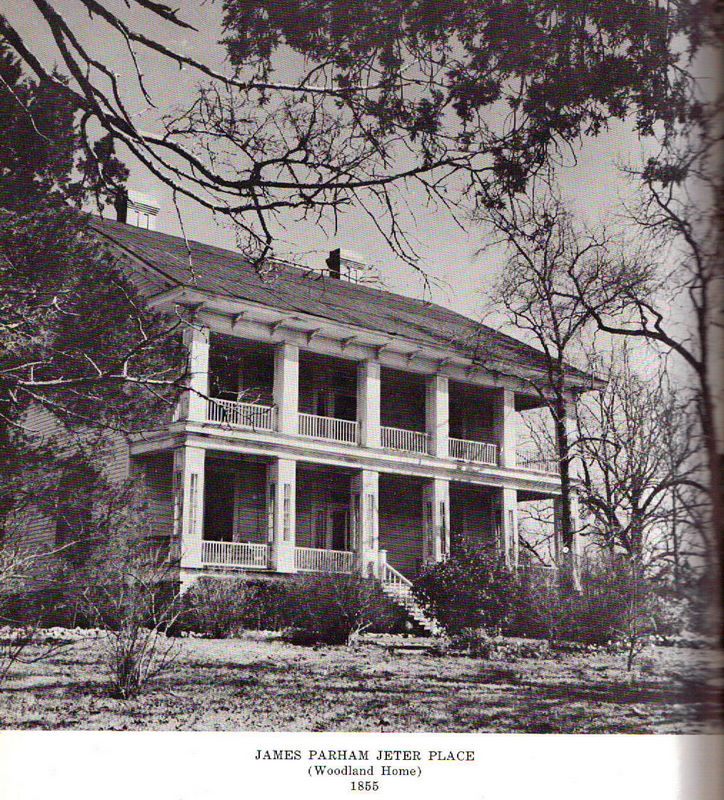

The historic Woodward Baptist Church – Image courtesy of Winthrop University’s Pettus Archives, 2024

Rains converted the dirt road from Chester to the Woodward Baptist Church into a muddy morass, evidently in places a quagmire. “The ambulance was too heavily laden in the deep mud, and as my maid was too weak to walk and my nurse unwilling, I walked five miles in the darkness in mud over my shoe tops, with my cheerful little baby in my arms.” The church sheltered women on the night of April 14th. “A little bride who had accompanied her husband, who was with the bank treasure, told me kindly, ‘We are lying on the floor, but have left the communion table for you out of respect. . . .’” Varina declined that offer because “the additional comfort of the table did not tempt one to commit sacrilege.” Parker was kind and attentive to Varina. He “slept in the pulpit, being the head of the party.” Varina slept in the first pew with her family members. It was a weary night, but the treasure train departed at daylight. W. S. Culpepper was a seventeen or eighteen-year-old young man and a midshipman with the treasure train. On that rainy first night he said Varina came to the door with a glass of wine to help him sleep. On April 15th Mrs. Isaiah Mobley provided breakfast for Varina and her family at Nine Mile Plantation. Mobley, a loving mother, for the rest of her life, told everyone she met, that her daughters “were held by the President’s wife.” The first day the company from the Navy Yard led the treasure train and the midshipmen followed. Some men walked alongside the wagons that contained the specie. On April 16th the two groups switched positions and this pattern continued.[24]

Morgan, the “Rebel Reefer,” recalled the first night out of Chester. “The midshipmen who were not on guard duty lay down under the trees outside in company of the mules.” An escort for Varina, he was attentive to every present

Image of the Historic Jeter House; Union Co., S.C., a “facsimile” of the Isaiah Mobley House known as Nine Mile Plantation. Mrs. Davis’s breakfast was served here in Chester Co., S.C. Courtesy of the Plantation Heritage by Marsh.

danger as the wagon train lumbered along sodden roads. “Not far away, on either flank and in their rear, hovered deserters waiting either for an opportunity or the necessary courage to pounce upon the, to them, untold wealth which those wagons contained. Five years of warfare had exhausted supplies and support for the war in the countryside.”[25]

The years of warfare distressed the isolated countryside. Clara Dargan Maclean, a refugee, returned home and along her route she saw “road-iron twisted like ribbons about the telegraph poles” as the first sign of destruction. “Below Chester began the ‘destruction of desolation.” Not a fence or house or living animal where once I had remembered such happy homesteads . . . embowered in orchards and gardens.” Of course, this was the route taken by so many thousands of veterans whose passage left a countryside as if it had had a visitation from a starving plague of locusts of biblical proportions.[26]

Varina found that food at “hostelries and even the private houses, was fifty cents or one dollar for a biscuit, and the same for a glass of milk.” She had difficulty feeding her children, “except when we reached the house of some devoted Confederate, and then I did not like to avail of their generosity.” Parker feared elements from Stoneman’s command were trailing him. He kept pressing on until he reached Newberry where a courier had a train waiting. The transmission of information within relatively isolated rural populations astonished Parker. “During the march I never allowed any one to pass us on the road, and yet the coming of the treasure was known to every village we passed through. How this could be was beyond my comprehension.” Varina also expressed fear from Union forces. “There were various alarms of ‘Yankees’ at Frog Level and other places on the road. . . .”[27]

Salem Presbyterian Church in Fairfield Co., Salem’s Crossroads where Varina Davis and her group were hosted after walking from Chester, S.C. Mrs. Davis and here ladies stayed nearby at the Means House. Courtesy of the Winthrop Un. Pettus Archives, 2024

The treasure train followed roads that ran parallel to the Broad River, and they spent the night at Salem Crossroads, located today on highway 34 between Newberry and Winnsboro. Parker had served on the USS Yorktown with Midshipman Edward C. Means and slept at his former shipmate’s home. Parker set a pace indicative of his concerns for safety. “One day we marched 30 miles, between our camp at Means’ and Newberry . . . I did more walking than anyone else.” Means “took all the ladies to his house and made them comfortable for the night.” They began very early the next morning and reached a pontoon bridge at noon. “That afternoon we arrived at Newberry, after a march of twelve hours’ duration.” Parker’s courier had a train ready to take his party to Abbeville. “We transferred the treasure to the cars and left the same evening at sunset.” The railroad station at Hope was three or four miles from the pontoon bridge on the south side of the river. The specie and passengers entrained at Hope, two or three miles beyond what is now Peak, on the bank of the Broad River. R. H. Fleming, a Midshipman, remembered they reached Newberry and “took cars for Abbeville. . . .” The Newberry Tri-Weekly Herald of Tuesday, April 18, 1865, reported that Mrs. Davis passed through Newberry on Sunday, April 16. The train reached Abbeville after midnight on April 16, so they arrived in town on the morning of April 17. Varina mentioned passing through Frog Level (today’s Prosperity) located between Hope and Newberry, but she gave no date.[28]

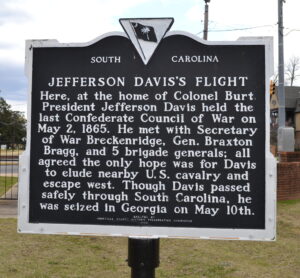

Joseph Henry Latimer of Atlanta was the engineer of the John C. Calhoun, a steam locomotive that transported Varina and her party to Abbeville on the spur track from the Greenville and Columbia railroad. The John C. Calhoun belonged to the Nashville, Chattanooga, and St. Louis Railroad Company, and was sent to Abbeville after Atlanta was captured. George W. Syfan was the engineer on the regular Greenville to Columbia train, and the engines were named the John Belton O’Neall and the Dar. The Dar “was small and had a peculiar smokestack but she was ‘the fastest on the line.’” Parker wrote that the John C. Calhoun’s passengers “arrived at the station in the middle of the night so all remained on board until the morning.” Varina and her “family left and went to the house of the Hon. Mr. Burt. . . .” Parker quickly formed a new wagon train, transferred “The Things,” on the morning of April 17, and “set off across the country for Washington, Georgia.” When James Morris Morgan departed Parker’s entourage in Abbeville, he found every residence surrounded by a garden: “a more fitting setting for a May Day festival than for the scene of the disruption of a government.” Burton Harrison experienced similar sentiments upon his arrival that May. “Abbeville was a beautiful place, on high ground; and people lived in great comfort, their Houses embowered in vines and roses, with many other flowers everywhere.” John Taylor Wood rode into Abbeville with Davis and was impressed with Armistead Burt’s house covered in roses. Wood’s father married Ann, Zachary Taylor’s oldest daughter. Wood was not only the grandson of an American President but was also the nephew of the Confederate President.[29]

CSA General Joseph Eggleston Johnston – Courtesy of Wikipedia

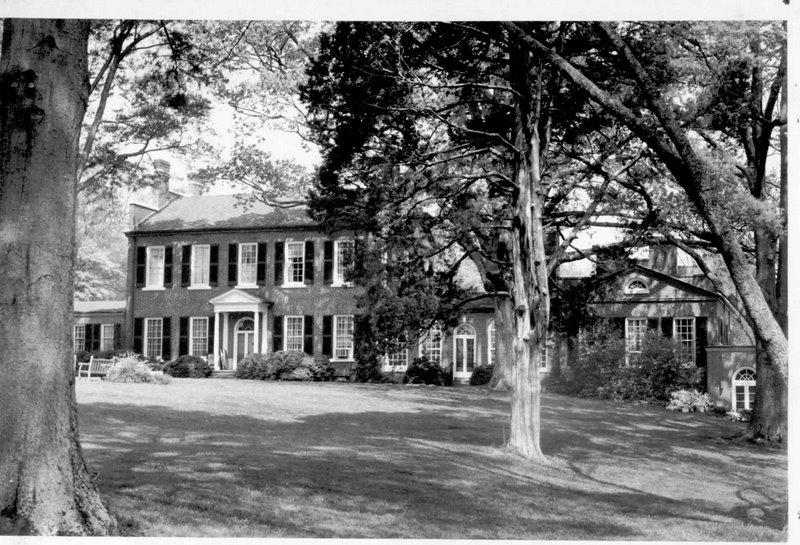

Historic Burt – Stark House in Abbeville, S.C. Courtesy of the Pettus Archives – Winthrop University, 2024

Armistead Burt, from Newberry, served in Congress and was an attorney in Abbeville. When Jefferson Davis entered the Senate in 1850 Burt was a member of Congress. The two families shared a rented house in Washington. Burt resided in a Greek Revival house on the north end of Main Street in Abbeville known today as the Burt-Stark Mansion. George A. Trenholm’s two daughters were refugees with Burt. Trenholm, who was said to have been the wealthiest man in the South in 1860, added about nine million dollars to his fortune with blockade runners. He purchased the Marshall House near Burt’s home to be used by refugees. Varina wrote to her husband that Armistead’s family provided more personal kindness than anyone else she had met on her trip. Maggie Howell became ill on the trip from Newberry and received rest in the Trenholm house “across the street.” Jefferson “Jeffy D.” Howell, Varina’s brother and a midshipman, became ill and was also housed at the Trenholm house. An apocryphal story is that Varina was reluctant to stay at the Burt house fearing Federal retribution for hosting the wife of Jefferson Davis. Burt replied, however, that “there was no better use to which his house could be put than to have it burned for giving shelter to the wife of a family of his friend.” This oft-repeated comment was not noted by Varina in her Memoir, but she understood their hospitality involved risk. She wrote that “Mr. Armistead Burt and his wife received us in their fine house with a generous, tender welcome, though fully expecting that, for having given us shelter, it would be burnt by the enemy.” She spent two weeks with the Burt family until she heard disturbing reports. Negotiations between Sherman and Joseph E. Johnston led her to realize that the surrender of the Army of Tennessee would force her husband to go west of the Mississippi and that the South was “at the mercy of Federals.” She instinctively knew she had to move.[30]

Henry Leovy, a refugee from New Orleans and friend of Jefferson, delivered her letter to Davis at Lafayette Young’s house in Laurens County on the lane known today as Jefferson Davis Road. Varina referred to these refugees from the Mississippi area in a 1905 letter. She wrote that when she was in Abbeville, “the Confederacy went to pieces.” When she received news of Lincoln’s assassination, she shed tears for his family, and for the “inevitable results to the Confederate President. I felt unwilling, if all was lost east of the Mississippi River, to hamper the Confederate President in his effort to reach the trans-Mississippi, and thereby enforce better terms than our conquerors seemed willing to grant.” She thought that her presence in Abbeville encouraged her husband to come to the town. Her message carried by Leovy informed Davis that she “would not wait his coming,” but would get out of the country and “meet him in Texas or elsewhere.” Varina’s presence in Abbeville may have contributed to Davis’ visit, but his destination was determined more by Union military pressure forcing him to abandon his original objective. Initially he planned to go to Anderson, cross the Savannah River west of that town at Hatton’s Ford, and continue by rail to the Trans-Mississippi South. Once Union forces blocked this route, Abbeville became his objective. From Abbeville he anticipated entraining in Washington, Georgia for the Trans-Mississippi region.[31]

Abbeville, as many communities in the rural Confederacy, attracted refugees from areas overrun by Union forces or confronted with military action. Refugees were appreciated for spending money, but there were tensions between permanent residents and refugees. It was natural for Harrison and Varina to rely on refugees who lived along the Mississippi River because the Davis family was part of a large network of families along that river. South Carolinians living elsewhere reflected the same attitudes as those found in Abbeville over the presence of refugees. Mary Elizabeth Anderson from Pleasant Falls near Spartanburg, wrote her brother John Crawford Anderson, a cadet at the Citadel, explaining the relationships that developed between refugees and their hosts. She reported some refugees in Spartanburg County were dissatisfied because they thought “the country people might put up with any and every privation for them.” She believed refugees should “be content with what they can get just now.” David Duncan, one of Wofford College’s first three professors, spoke very severely to a “Charlestonian who was complaining a good deal, and at length silenced him.” Mary Anderson’s parents were talking of hosting a refugee, but she opposed the idea. “We might take them in for the sake of humanity but if they can go elsewhere, I say let them go.” Refugees at her grandfather’s house were “very much dissatisfied” with food but the garden was producing delicious vegetables. In contrast Harriet “Hettie” Thomas from Mount Hope in the Ridgeway section of Fairfield District, corresponded with her cousin, Elizabeth “Lize” Catherine Palmer, a Charleston refugee. Hattie was delighted that Lize was safe and received good treatment. Mary Anderson lived in an Upcountry yeoman farmer culture while Hattie was related to the Charleston elite. Lize was a refugee with her aunt, Mrs. Richard Yeadon, wife of the Charleston Courier editor. Fine gradations of social position meant everything in antebellum South Carolina. A proud, self-sufficient, and industrious Upcountry family could quickly take offense at what was perceived as feelings of superiority among Low Country elites. In Abbeville District there were connections between the town’s first families and refugee elites.[32]

William Pfifer Home in Charlotte, N.C. also spelled William F. Phifer: George and Anna Trenholm (Secretary of Treasury the last year of the war) roomed with William F. Phifer when Davis was in Charlotte, N.C.. Trenholm was elderly and ill so he resigned in Fort Mill. Since he could not get around with ease Davis held meetings in the Phifer House.

Jefferson Davis was in Charlotte by April 23 when he sent a message to Armistead Burt introducing his secretary, Burton Harrison, who was traveling to Abbeville to assist Varina. Harrison entrained in Charlotte with his horse, rode to Newberry and took the train to Abbeville. He had only Confederate money and found that it was no longer accepted. In Newberry an inquisitor asked if he had any news about Mr. Trenholm. Harrison told the man he would have to wait until he boarded his horse and then he would tell everything about Trenholm because he had recently been with him. Harrison had acquired a traveling partner in Chester, also bereft of funds. His companion laughed as they boarded horses with the man because Harrison’s knowledge of Trenholm had secured food and a bed. The inquisitor, a Newberry banker, provided exquisite hospitality. The next morning after breakfast they departed with a haversack of supplies as they entrained for Abbeville.[33]

Armistead Burt and Harrison urged Varina to leave Abbeville. Davis wrote a letter to Varina when she was in Abbeville, asking her to hasten to “seek safety in a foreign country.” He suggested that she try to escape to Texas or a foreign country. He wrote that he intended go to Texas and if he had problems he could cross into Mexico and find some place in the world. Harrison found a refugee, John S. Williams of Kentucky, who was recuperating in the countryside south of Abbeville. Williams was on a farm owned by Nathaniel Jefferson Davis, known to one and all since childhood as “Jeff Davis.” Williams feared if he loaned wagons and horses, he might never get them back because equines were stolen constantly. “But he gallantly devoted them to Mrs. Davis, putting his property at her service as far as Washington, Georgia, and designating the man to bring the wagons and horses back. . . .” Harrison never knew if they were returned. Another nearby refugee, Judge Thomas Monroe of Kentucky, Henry J. Leovy’s father-in-law, and his family were refugees in Abbeville. Jefferson Davis, a friend of Monroe, sympathized with him because he was “driven from the land of his birth” to become a refugee. Monroe hosted three Kentucky cavalrymen, Leeland Hathaway, Jack Messick and Winder Monroe who were on sick leave with Judge Monroe. They were capable of accompanying Varina to Washington.[34]

Varina remained in Abbeville until April 29. Her departure on that Saturday was prior to a burial reported by Fannie Calhoun Marshall. Women in Abbeville, like those in Chester, did their best to care for wounded and ill soldiers. One such soldier with smallpox was isolated and nursed but died on May 2. He was buried at the foot of Secession Hill, just above the railroad tracks. Fanny Marshall speculated that he could have been “the last soldier who gave up his life for the cause. His grave is marked by a cedar, planted by a little girl who never forgot to place flowers on his grave.” Everyone in Varina’s group had been vaccinated except Winnie, Varina’s baby. The entourage stopped at Hohenlinden, John Oliver Lindsay’s plantation, on the ridge above Vienna. Lindsay found an African American boy with smallpox from whom he extracted a fresh scab. Lindsay performed the inoculation. Hohenlinden was twenty miles from both Abbeville and Washington, an ideal location for Varina to spend the night. There is no documentation, however, identifying where she stayed on the night of April 29. The party continued across the pontoon bridge connecting Vienna with Petersburg in Georgia, then traveled to Washington, passing through Chennault and Danburg. Harrison was the guest of John Joseph Robertson, a bank cashier who lived in the bank building. Jefferson Davis stayed with the Robertsons after Harrison left.[35]

Varina remembered that on April 29, “about half an hour’s travel out of Abbeville, our wagons met the treasure” returning. Parker had taken the Confederate specie from Abbeville to Augusta, encountered federal forces around Augusta, and returned to Abbeville. Charles Iverson Graves and some midshipmen, with Parker’s permission, left from Augusta homeward bound. Parker found Washington “in a state of most depressing disorder.” News of Joseph E. Johnston’s surrender resulted in quartermasters and commissaries being looted. This sort of pillaging by local citizens, deserters, soldiers going home, and others of that ilk, occurred in Virginia, Charlotte and Greensboro as well as Griffin and Augusta in Georgia. Robert M. Willingham blamed a Texas regiment for a riot in Washington, Georgia on May 1, 1865. Anger over the scarcity of rations, they broke into commissary goods and were joined by other soldiers and local residents. “By the end of the day, there was little food left, most cloth, thread, paper, and pens destroyed, and many horses and mules stolen.” The next day pillaging became more rampant, ordnance stores at the depot were taken and the commissary cleaned out. On May 3rd proles stole equines, even unhitching two horses on the town square. Willingham succinctly stated the situation, “By May 2nd Washington was a madhouse with the inmates running the asylum.”[36]

Harrison sent a private message by Henry Jefferson Leovy to Jefferson Davis at 7:30 a. m. on April 29. “We had intended starting yesterday afternoon, but we were detained by the rain. Are just getting off now. The ladies and children are very well, in good spirits. They move in a good ambulance and carriage and will reach Washington in two day’s drive from this place.” He explained this plan was “determined by your telegrams, and by the belief that you would move westward, along a line from this place.” Harrison notified Davis that Henry Leovy would verbally “explain our plans, &c. He will tell you everything.” Leovy was born in Augusta in 1826, moved to New Orleans and studied law under Judge Thomas D. Monroe in Frankfort, Kentucky. He published a codification of New Orleans laws, a book on Louisiana laws, and edited the New Orleans Delta. During the Civil War he was appointed as a military Judge in Virginia with the rank of Colonel of Cavalry.[37]

After arriving in Washington on April 30, Harrison went to the quartermaster’s camp near Washington, obtained army wagons with four good mules for each, and the best harnesses available. He secured a driver for each team, “and several supernumeraries, friends of theirs, were recruited there, with the promise, on my part, that the wagons and mules should be divided between them at our journey’s end.” All were from Mississippi, so by volunteering to help Varina they were traveling toward their homes. To be safe the Harrison group went some distance from the quartermaster’s camp, a wise move. During the night the quartermaster’s camp was raided and all the healthy equines, including exceptionally strong mules belonging to Louis T. Wigfall, were stolen. Willingham believes the raid was by the Eighth Texas Cavalry, known as “Terry’s Texas Rangers,” who stole rations out of frustration. The next morning, May 2, Harrison and Varina departed with wagons loaded with supplies sufficient to “take us to Madison,” a Georgia town on the route to Florida. Harrison lacked sleep and was weak because he had been sick with a terrible bout of dysentery. The party consisted of Harrison, Varina, her sister Maggie Howell and four children, her maid Ellen Barnes, and coachman James H. Jones, who drove Varina’s horses from Richmond. The Kentucky cavalrymen, Leeland Hathaway, Jack Messick and Winder Monroe, remained with Varina. Colonel George Vernon Moody, an attorney from Port Gibson, Mississippi, and Major Victor Moran of Louisiana, accompanied her for the duration of her flight. Varina’s brother Jefferson Howell, who had been paroled, joined her. William Wood Crump, an assistant to the Secretary of the Treasury who administered the day-to-day functions of the office in Richmond, carried a small fund with him. He was a refugee in Washington. He gave a few hundred dollars for Harrison’s group and $110 to Varina, loans to be repaid from Harrison’s and Davis’ future salaries. Later Crump contributed to the bond to release Davis from prison. Everyone was sworn to secrecy and the party left in a due south direction. Nugent, Jefferson Davis’ nephew-in-law, delivered a message expressing Davis’ “bitter regret” that he arrived in Washington too late to see Varina. Nugent returned with Varina’s request that Davis not “seek an interview” because it could compromise his safety.[38]

On May 2 at 10:15 a. m. Harrison sent a message to Davis from Washington, Georgia. He had “excellent drivers, teams, and conveyances, a supply of forage and provisions and are prepared for a long and continuous march. The ladies and children are well and have been kindly entertained at Dr. Ficklen’s, where they still are. . .” Fielding Ficklen was born on December 23, 1801, in Wilkes County, Georgia. He had seven children and seven female slaves in 1850. In 1839 he graduated from the University of Pennsylvania Medical School with a major in Gastritis. Varina and the children were at the Ficklen home on the nights of April 30 and May 1, 1865. Harrison reported to Davis that Varina was very anxious to see him but was willing to leave before he arrived if that were preferable. On May 2 at 10:15 a. m. Harrison sent a message to Jefferson that Johnston’s surrender of all territory east of the Chattahoochee River necessitated a change in plans, and he thought it best to “carry her to a place of safety in or beyond Florida.” Davis responded on May 3 at 9:00 p. m. that his family “is safest when farthest from me.” Harrison moved the wagon train with Varina and the children out of Washington on May 2, the day Jefferson and the five brigades left Abbeville at 11:00 p. m., bound for Washington. Varina remembered they pitched tents and made tea “in the awkward manner of townspeople camping out.” She recalled, “the ground felt very hard that night as I lay looking into the gloom and unable to pierce it even by conjectures.” She was a woman of strong constitution, stronger will, and always a rock of support for the man she loved.[39]

Footnotes – Chapter Two:

[12] Burton Norvell Harrison, “The Capture of Jefferson Davis,” Century Magazine, November 1883, reprinted in Jesse Burton Harrison, ed., Saris Sonis Focisque: Being a memoir of American Family, The Harrisons of Skimino, and Particularly of Jesse Burton Harrison and Burton Norvell Harrison (privately printed, 1910, London: Dalton House, Forgotten Books, n.d.), 225-26. James Morris Morgan, Recollections of a Rebel Reefer, (New York: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1917), 229-33. James C. Clark, Last Train South: The Flight of the Confederate Government from Richmond (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, Inc., 1984), 5-7. William Harwar Parker, “The Gold and Silver in the Confederate States Treasury: What Became of it,” SHSP, vol. 21, 1893, 306, 307. Parker, Recollections, 356. Varina Davis, Jefferson Davis, Ex-President of the Confederate States of America, A Memoir by His Wife. (New York: Belford Company Publishers, n.d.), reprint by Kessinger Publishing. vol. 2:608, 611. Hattaway and Beringer, Jefferson Davis, 386. Burke Davis, Long Surrender, 15. Samuel Emory Davis (1852-1854), the first child, called “le man” by Jefferson, died from measles and died at the age of 1 year and 11 months. Margaret Howell Davis Hayes “Maggie” died at the age of 45 on July 18, 1909. “Jeff, Jr.” contracted Yellow Fever and died when he was 21. Billy died of diphtheria on his 11th birthday (October 16, 1872). Winnie died on September 18, 1898, a month after she contracted an illness from riding in an open carriage in an Atlanta parade, substituting for Varina who was ill. C. Vann Woodward, ed. Mary Chesnut’s Civil War, (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1981), 776.

[13] Cashin, First Lady, 145-146, 160,165. James mentioned the name Brooks. The 1870 Census lists a twelve-year-old African American, James Lambert, living in Pleasant Grove, Lunenburg, Virginia. Woodward, Mary Chesnut’s Civil War, 568.

[14] Nelson D. Lankford, ed, An Irishman in Dixie: Thomas Conolly’s Diary of the Fall of the Confederacy (Columbia, The University of South Carolina Press, 1988), 38. Burke Davis, Long Surrender, 15. Wikipedia, accessed November 13, 2023, describes the many variations of a slouch hat, including those worn by Union and Confederate armies, Australians, and Americans in western and southern states.

[15] Morgan, Rebel Reefer, 229-33. Davis, An Honorable Defeat, 67, citing Leeland Hathaway Recollections, Southern Historical Collections, University of North Carolina, 110-111. Lankford, An Irishman in Dixie, 38. Harrison, Memoir, 225- 26 227, 236, 242-43. Burke Davis, Long Surrender, 28. Joseph E. Johnston, Narrative of Military Operations (Columbia, South Carolina: Made in the USA reprint of the 1873 original, no pagination), Chapter 12. Tate, Rise and Fall, 274-75. Hattaway and Beringer, Jefferson Davis, 398-99, 499. Today the Sutherlin mansion houses the Danville Museum of Fine Arts and History at 975 Main Street. The Macon (Mississippi) Beacon, January 20, 1911, 2, copied Jane Patrick Sutherlin’s obituary from a Danville newspaper.

[16] Harrison, Memoir, 227, 243, 243. Davis, Honorable Defeat, 176. Weill was also spelled “Weil” and his home was used by members of Jefferson Davis staff when they stayed in Charlotte for a few days later in April.

[17] William Harwar Parker, Recollections of a Naval Officer, 1841-1865, (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1883), Miami, Florida: HardPress Classic Series reprint, 355-356. William Parker, “Gold and Silver,” 304-313. Davis, Honorable Defeat, 214. John W. Harris, “Confederate Naval Cadets,” CV., vol. 12, April 1904, 171. Harris quoted from the diary of Midshipman R. H. Fleming, a member of the Treasure Train crew. The dates in Parker disagree with those from Fleming’s diary. Fleming’s dates appear more reliable.

[18] Harris, “Naval Cadets,” 171. John C. Stiles, “The Confederate States Naval Academy,” CV,” vol. 23, September 1915, 402. Stiles’ dates seem more correct, but he failed to date every day. Varina Davis, Memoir, vol 2, 608. The railroad to Columbia from Charlotte ran from Chester to Columbia. At Alston there was a junction with the railroad from Columbia to Greenville that crossed the Broad River between Alston and Hope (later Peak). This railroad went to Prosperity, (in 1865, “Frog Level”), Newberry, Greenwood, and Hodges where there was a spur to Abbeville. The bridge over the Broad River had been burned by locals to foil Sherman, but a pontoon bridge was available. Davis, Honorable Defeat, 214-217. Burke Davis, Long Surrender, 25, 53, 60, 65.

[19] Mrs. James Conner, et. al. eds. Eugenia C. Badcock, “Personal Recollections of the War Between the States,” South Carolina Women in the Confederacy, vol. 2. (Columbia: The State Company, 1907), pp. 143-44. South Carolina Division, United Daughters of the Confederacy, eds. Recollections and Reminiscences, 1861-1865 Through World War I, Ann Poag Hickin, “Sketch of the War Life of Mrs. Leroy D. Poag, nee Mattie Steele” vol. 1, published by the UDC (1990), pp. 621-22. Joseph M. Gettys, My Cup Runs Over: “Life is Full, Life is Fun!” (Columbia: The R. L. Bryan Company, 1996), 2-3. Caroline E. Janney, Ends of War: The Unfinished Flight of Lee’s Army after Appomattox (Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press2021), 135.

[20] South Carolina Division, United Daughters of the Confederacy, Recollections and Reminiscences, 1861 Through World War I, vol. 1, 1900, Catherine Bradley Hood, “Behind the Lines – The Achievements and Privations of the Women of the South – A Memorial,” pp. 597-98. Woodward, Mary Chesnut’s Civil War, 764, 766, 777, 785, 790, 800. Mary was in Chester by March 21 and on May 2 she was back in her home near Camden, South Carolina. Chester County Historical Society, A Walking Tour of Chester S. C. (Chester, South Carolina: 107 McAliley Street, n. d.), 14. DaVega, spelled DaVaga in sources but DeVega in the census records, operated a hotel in 1850. His wife, Eliza McClure DaVega and Davega children.

[21] Woodward, Mary Chesnut’s Civil War, 783 – 785. This source provides the key to the chronology of the trip. The train left Charlotte on April 14, arrived in Chester on April 15. Page 784 is a picture of Mary Boykin Chesnut’s handwritten 1880s manuscript clearly dated. Lowry P. Ware, Old Abbeville: Scenes of the Past of a Town Where Old Time Things are not Forgotten (Columbia: SCMAR, 1992), 96. Jefferson Davis, Rise and Fall, 247, 319, 321, 326. As a Colonel, Chesnut was an aide-de-camp to P. G. T. Beauregard in 1861. From 1862 until the end of the war he was with Davis.

[22] Parker, Gold and Silver, 306, 307, Parker dated their arrival in Chester as April 12. Parker, Recollections, 356. Varina Davis, Memoir, vol. 2, 611. Woodward, Mary Chesnut’s Civil War, 800. Burke Davis, Long Surrender, 73. Richard Nugent carried information from Jefferson Davis to Varina outside Washington, Georgia and was identified as Jefferson’s nephew-in-law.

[23] Fredrick W. Moore, ed., “The Diary of Kinloch Falconer,” CV, vol. 9, September 1901, 409.

[24] Varina Davis, Memoir, vol. 2, 611-12. Parker, Gold and Silver, 307. Parker, Recollections, 356. Michael Ballard, A Long Shadow: Jefferson Davis and the Final Days of the Confederacy (Jackson: University of Mississippi Press, 1986), 119. Mrs. James Conner, et. al., eds. Carolina Women in the Confederacy, vol. 2, (Columbia: The State Company, 1907). Eugenia C. Babcock, “Personal Recollections of the War Between the States,” 145-46. Mrs. John Wilkes, “The Confederate Naval Yard in Charlotte, N. C.,” SHSP, vol 40, 187. James C. Clark, Last Train South, 66. Burke Davis, Long Surrender, 73. Hanna, Flight to Oblivion, 34. Hanna identifies Mrs. Mobley’s home where the group had breakfast as being on the Ashley Ferry Road.

[25] Morgan, Rebel Reefer, 234.

[26] Clara Dargan Maclean, “Return of a Refugee,” SHSP, vol. 13, 507. Burke Davis, Long Surrender, 74.

[27] Parker, Recollections, 358. Ware, Old Abbeville, 96 Ware quoted Burton Harrison from the November 1883 issue of Century Magazine. Varina Davis, “Memoir,” vol. 2, 611, 612.

[28] The Newberry Tri-Weekly Herald, Tuesday April 18, 1865. The paper stated that General Hood and Mrs. Davis passed through Newberry on Sunday. Varina Davis, Memoir, vol. 2, 611, 612. Parker Recollections, 357-58. Burke Davis, Long Surrender, 74-75. Davis, Honorable Defeat, 215. Hope was about three miles from the Broad River, replaced later with Peak, on the bank of that stream.

[29] Abbeville Medium, March 10, 1898. Robert R. Hemphill had lunch with J. H. Latimer on March 3, 1898, and reported the substance of their conversation. Parker Recollections, 357. Harris, “Naval Cadets,” 171. Morgan, Rebel Reefer, 235. Harrison, “Memoirs,” 245. Royce Gordon Shingleton, John Taylor Wood: Sea Ghost of the Confederacy (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 1979), 3-4, 155. James C. Clare, The Last Train South, 32. Burke Davis, Long Surrender, 75.

[30] Cashin, First Lady, 54. Ware, Old Abbeville, 96-97. Ware cited the Abbeville Press and Banner, September 18, 1863, on the Trenholm purchases. Varina Davis, Memoir, 612, 615. Morgan, Rebel Reefer, 237. Harrison, “Memoirs,” 245. Burke Davis, Long Surrender, 45-46.

[31] OR., series I, vol., 47, part 3, 832. Varina Davis, Memoir, vol. 2, 615. Varina stated that Henry Leovy was to meet Davis at the Saluda River with her letter. The river was not far from Lafayette Young’s house, standing on Jefferson Davis Road today.

[32] Ware, Old Abbeville, 96-97. Tom Moore Craig, ed., Upcountry South Carolina Goes to War: Letters of the Anderson, Brockman, and Moore Families, 1853-1865. (Columbia: The University of South Carolina Press, 2009), 89-90.

[33] OR., series I, vol. 47, part 3, 832. Davis, Memoir, 615-16. Harrison, “Memoir,” 244.

[34]https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/7489837/leeland-hathaway, accessed October 3, 2023, Hathaway, a Lieutenant in the 14th Kentucky cavalry, was captured and released just as the Confederacy collapsed. He was in Abbeville when Varina arrived and decided to accompany her. Hattaway and Beringer, Jefferson Davis, 413-15. Davis, Honorable Defeat, 292. Leeland Hathaway, “Recollections,” Southern Historical Collections, Wilson Library, The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, accessed on-line. The Times-Democrat (New Orleans), October 4. 1902, 4. Henry Leovy studied law under Judge Monroe.

[35] Fannie Calhoun Marshall, “Reminiscences of Fannie Calhoun Marshall,” UDC, vol. 10. 75. Varina Davis, Memoir, vol. 2, 615. Harrison, “Memoir,” 245-46, 246-47. Harrison spent two nights and a day in Washington. Varina described camping out near Washington. Jefferson Davis, The Rise and Fall of the Confederate Government, vol. 1 (Richmond: Garrett and Massie, 1938, originally published in 1881, Da Capo Press paperback edition, 1990), 342. Bobby F. Edmonds, The Making of McCormick County (McCormick, South Carolina: Cedar Hill, 1999), 254. Burke Davis, Long Surrender, 89-90. E. Merton Coulter, Old Petersburg and the Broad River Valley: Their Rise and Fall (Athens: The University of Georgia Press, 1965), 31, 48, 70. Tate, Rise and Fall, 269. The Census of 1850, Washington, GA, dwelling, 649, family 639. The Census of 1870, Washington, Georgia dwelling 123, family 124 includes Mary E. Robertson, “keeping house.” There is no Find-A-Grave or any other listing for Elizabeth Hay Robertson. Davis, Honorable Defeat, 259-60, 267-68.

[36] OR., series I, vol. 49, chapter 6, part 2, 1274. Varina Davis, Memoir, vol. 2, 615-16. Burk Davis, Long Surrender, 130-1341. Parker, Recollections, 363, 365, 367, 369. Hattaway and Beringer, Jefferson Davis, 418. Davis, Honorable Defeat, 214-18. Janney, Ends of War, 172, 174-75. Robert M. Willingham, Jr., The History of Wilkes County, Georgia (Washington, Georgia: Wilkes Publishing Company, 2002), 180. This work was brought the writer’s attention by Linda Crowe Chesnut whose assistance is greatly appreciated. She has been able to find images that add immeasurably to this work. Robert M. Willingham, “‘It’s All Over:’ Jefferson Davis and the Final Acts of the Confederate Government in Washington, Georgia,” unpublished manuscript, described to the writer by Robert Willingham, March, 2024. Robert M. Willingham, Jr., No Jubilee: The Story of Confederate Wilkes (Washington, Georgia: Wilkes Publishing Company, 1976), 202-203.

[37] OR., series 1, vol. 49, part 2, 1269, 1274, 1275, 1277, 1278. The Times-Democrat (New Orleans), October 4, 1902, 4.

[38] Harrison, “Memoir,” 247-50. Varina Davis, Memoir, 2:615-617, 644-45. Daily Southern Reveille, 9 (Port Gibson, Mississippi) Nov. 27, 1858, 4. This issue included an advertisement by George Vernon Moody, attorney. Vicksburg Evening Post, September 26, 1895, 4.. Burk Davis, Long Surrender, 131. Burke Davis identified Richard Nugent as Jefferson Davis’ nephew. H. C. Binkley, “Shared in the Confederate Treasury,” CV, 38. March 1930, 87-88. The Constitution (Atlanta), April 17, 1934, 9. Henry Clay Binkley enlisted at the age of 25 and served under Nathan Bedford Forrest. Varina Davis, Memoir, 2:617. Harrison, “Memoir,” 247. Harrison did not identify where Varina stayed but wrote she was “comfortably lodged in the town.” Mrs. Jefferson Davis, New York City, to S. A. Cunningham, October 13, CV, November 1905, 486-487. Varina defended Jefferson Davis against an article critical of his “leisurely” ride through South Carolina. Willingham, “‘It is All Over’”. Wikipedia article on William Wood Crump. Find-A-Grave article on William Wood Crump. The Virginia Magazine of History and Biology, vol. 5, January 1889, 349, Crump Necrology. The Savanah Morning News, February 28, 1897, 1. Crump obituary.

[39] OR., series 1, vol. 49, part 2, 1269, 1274, 1275, 1277, 1278. Find-A-Grave, Census of 1850 and 1860, “College Students Lists”, The Philadelphia Inquirer, April 4, 1823, 3. Varina Davis, Memoir, 2:617. Willingham, History of Wilkes County, 180.

________________

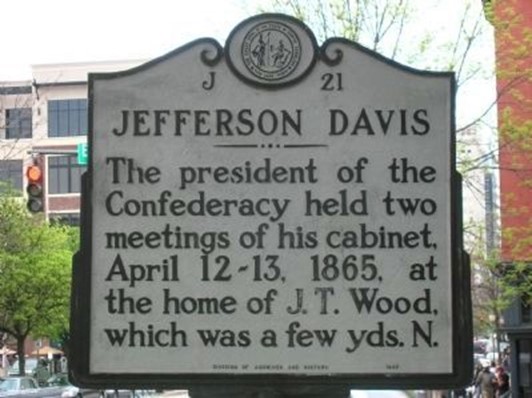

Chapter Three: Danville – End of the Confederate Government

“It would be one of the greatest of human crimes for us to attempt to continue the war; for, having neither money nor credit, nor arms but those in the hands of solders, nor ammunition but that in their cartridge-boxes nor shops for repairing arms, . . .”

Joseph E. Johnston to Jefferson Davis, April 13, 1865

Herman Hattaway and Richard E. Beringer’s seventeenth chapter in Jefferson Davis, Confederate President is titled “The End in Virginia” and the next chapter is entitled “The Pseudo-Confederacy.” From the perspective of more than 150 years their nomenclature appears excellent. Davis wrote to Lee on April 12, 1865, that the Tredegar Iron Works lacked sufficient supplies to keep men working. Varina remembered this period in her Memoirs. “Events now rapidly culminated in the overwhelming disaster he and our brave people had striven so energetically to avert. The gloom

William T. Sutherlin’s mansion in Danville, Virginia. Built for Sutherlin in 1859. William T. Sutherlin’s Danville home where Davis stayed May 3-10. Courtesy of The Danville Museum of Fine Arts and History

was impenetrable.” The war was lost. Davis left Danville in a positive mood, thinking the Confederacy could recover. There were 140 miles of disintegrated railroad tracks between Richmond and Danville, reducing the speed to an average of about ten miles an hour. At one location the floor of a car collapsed “throwing a half dozen screaming soldiers under the moving wheels.” During some delays, citizens approached Davis’ car “to gawk at the Chief Executive or shake his hand.” When Davis disembarked, Danville became the temporary Confederate capital. But before government workers could find their way to Danville, secure space and unpack boxes, Davis was in Greensboro. Workers left Danville for home before they could function, and the government disintegrated.[40]

By April 13 Danville had the first working railroad south of Richmond, and on that morning over 3,000 Confederate veterans arrived. “For several days the men flowed out just as they flowed in.” But the railroad was unable to maintain service and an ammunition explosion exacerbated the situation, plunging the town into chaos.[41]

Henry Wemyss Feilden, Assistant Adjutant General for the Department of South Carolina, Georgia and Florida, understood the situation and thought the cause was hopeless by March 22. On April 6 he wondered “what our leaders are going to do; a prolongation of the war appears nothing but a further useless loss of life.” His analysis was identical to that of his leaders.[42]