The Yorkville Enquirer reported on March 21, 1872 – “The American Colonization Society was organized in Jan. 1817 and incorporated on March 22, 1837. The constitution was drawn up by Rev. Alexander McLeod of the Reformed Pres. Church. The goal is to colonize people of color from the U.S. to Africa. The society publishes a periodical called, The African Repository. So far they have settled 13,598 in Africa of whom 1,230 were from S.C.”

On Nov. 28, 1872 the Yorkville Enquirer reported – “We learned a number of the Negroes who went to Liberia from Clay Hill last November have returned to the U.S. and landed at Boston a few days ago. Among others, the following have returned and are expected back at their old homes in a few days: Francis Johnson and Family, Minor Cathcart and family, John C. Moore and family, Madison Simril and family, the children of Bob Tate, and the children of Samuel McCollum.”

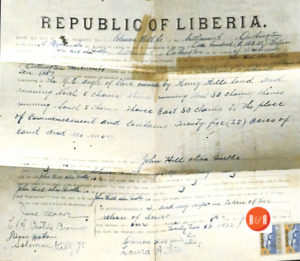

City Directories and History: The Yorkville Enquirer on Nov. 2, 1870 Gone to Liberia – One Tuesday a colony of 136 negroes left the vicinity of Clay Hill the location of Hill’s Ironworks, under the auspices of the American Colonization Society. From Yorkville they traveled to Rock Hill on the train and then were headed to Baltimore. The group plans to sail on the ship Golconda, which belongs to the colonization society. Heads of families include: Rev. E. Hill, June Moore, Andy Cathcart, Minor Cathcart, Solomon Hill, Peter Watson, John Moore, Madison Simril and George Simril. The Alexandria Gazette Nov. 2, 1870 printed, – Yesterday the ship Golconda left Baltimore for Liberia with a large number of cabin passengers.

The Richmond Daily Dispatch reported on Nov. 4, 1870 – Arrived today Fort Monroe: ship Golconda from Baltimore. She will receive about 300 additional emigrants from Norfolk and sail for Liberia. The Daily Dispatch reported on Feb. 24, 1871 – the ship Golonda from Liberia went ashore on Nantucket Shoals and was lost….

The Yorkville Enquirer reported on Feb. 22, 1872 – A letter from Rev. Elias Hill of Liberia dated Jan. 3, 1872 from Monrovia, Liberia. The letter stated, “they have arrived with 244 passengers, most of whom are from S.C. but including 68 from Ga., 5, from Florida, 5 from N.C., and one from Virginia. The ship arrived in Liberia on Dec. 15, 1871. The letter described the voyage as extensive high seas and rough weather. The Captain of the ship was A. Alexander of N.Y. During the voyage two children were lost to death. Rev. E.T. Dillon of the Pres. Church of Liberia held services for one of the children. Also on the voyage two female babies were born and one was born to Elizia Watson of Clay Hill and the other to Rachel Garrison. Immigrants from S.C. are now selecting land and expect to farm for cotton, corn, and livestock.”

The Yorkville Enquirer reported on Jan. 16, 1879 – “The famous ship Azor, which belongs to the Liberian Emm. Association, arrived in Charleston last Friday from London. The prospects for another voyage to Liberia do no look good.”

The Yorkville Enquirer reported on March 20, 1879 – “The ship Azor, which belongs to the Liberian Exodus Association has been liable in federal court in Charleston in the sum of $6,783., most of which is due to the captain and mate. It is claimed that the vessel is worth $25,000., but the association can’t pay the claims against her and she will be sold.”

The Yorkville Enquirer reported on April 26, 1883 – “Last Thursday a group of nine colored people arrived home from Liberia including two women and seven children. The left two years ago for Liberia. They have now come home to Concord, N.C. to the Phifer Plantation. Their white friends paid for their return trip, which took two months. They are afflicted with a disease which has caused their feet to swell and some toes to fall off. They have many friends who remain in Liberia and are sick and impoverished but have no way of returning.”

The Yorkville Enquirer reported on April 17, 1884 – “Mary Rouse is being carried for in Atlanta. She left Alabama in 1878 with a party of 76 people to go to Liberia. Many of these suffered from fever, and only ten of the 76 survived. Two have returned to America. Mary was saving the hold time she was in Liberia in order to return to Alabama and she saved $56., which paid for her passage to NY and she is now on the way home.”

The Yk Enquirer reported on Dec. 22, 1886 – “About thirty colored persons left Rock Hill Sunday afternoon bound for Liberia. They boarded the train and stopped at Fort Mill where three hundred others joined them to board a special train to NY City. That train never arrived. It turned out this was a scam and someone sold tickets that were no good. Many of the people had sold most of their properties to buy the tickets.”

The Rock Hill Herald of July 21, 1887 contained a story from the Lancaster Review – “A colored tenant on Mr. John D. Taylor’s plantation has received a letter from one of his kinsman who went to Liberia on the Azor. In this letter he pleads most eloquently for money to return to S.C. He says he will obligate his labor for the rest of his life to anyone who will play for his passage. He is in destressed condition, boarding or starvation.”

Many of the early nineteenth century opponents of slavery believed the system should be abolished gradually and the freed slaves returned to Africa. In 1817, a number of prominent Americans, including Henry Clay, Bushrod Washington (a nephew of George Washington), Francis Scott Key and United States capitol designer, William Thornton–all slaveholders–formed the American Colonization Society with the idea of repatriating African American slaves and freedmen in their “homeland.” The society was granted possession of Cape Mesurado on the west coast of Africa by local chiefs, and founded the country of Liberia whose capital was named Monrovia for James Monroe.

With great hopes of solving the problems of slavery, the first colonization in Liberia took place in 1820; but repatriation was slow. By 1860, after 40 years in existence, the society managed to relocate fewer than 10,000 African Americans (some say 6,000)–less than 0.3 percent of the black American population increase for that period. In another ten years Liberia’s population had increased to only 19,000 including descendants and new arrivals.

Perhaps it was the lack of support that slowed emigration. Not everyone agreed the ACS had the right approach. Opposition to the society came from three groups: Southern proslavery advocates, free blacks who considered themselves Americans and not Africans, and abolitionists who considered the society to be racist for assuming that the slavery issue could be solved by colonization.

By the 1840s the ACS was facing bankruptcy, and in spite of the society’s ardent requests for the United States to claim sovereignty over the colony, Washington declined. With so much opposition, bankruptcy and the lack of cooperation from the United States government, the society demanded the colony to declare independence. With little choice in the matter, Liberia became an independent republic in 1847–the first democracy on the continent of Africa.

- Mr. Clarence Hill who migrated to the US from Liberia in the 1990s.

- Celebration of the Liberian Movement at Allison Creek Pres. Church – 2017 (Images courtesy of the Spencer Anderson Collection)

The Liberian founders made unexaggerated efforts to secure the liberty and prosperity of its citizens. Although their constitution was modeled after the United States Constitution, white men of the ACS suggested whites be excluded from voting and holding government office. The young government, in hopes of increasing its population made provisions to apprentice any under aged emigrant to responsible people to teach them a trade, skill and provide basic education. At the age of adulthood these were given $12.00 by the government and 5 acres by the Colonization Society.

Following the American Civil War and Emancipation, Southern freedmen became more aware of Liberia and its government made up of freed blacks. The rise of the terrorist organization known as the Ku Klux Klan caused many freedmen to seriously consider emigration. Some York County men, and others, who had experienced Klan brutalities were convinced life had to be better in an unfamiliar land than face terrors in the night.

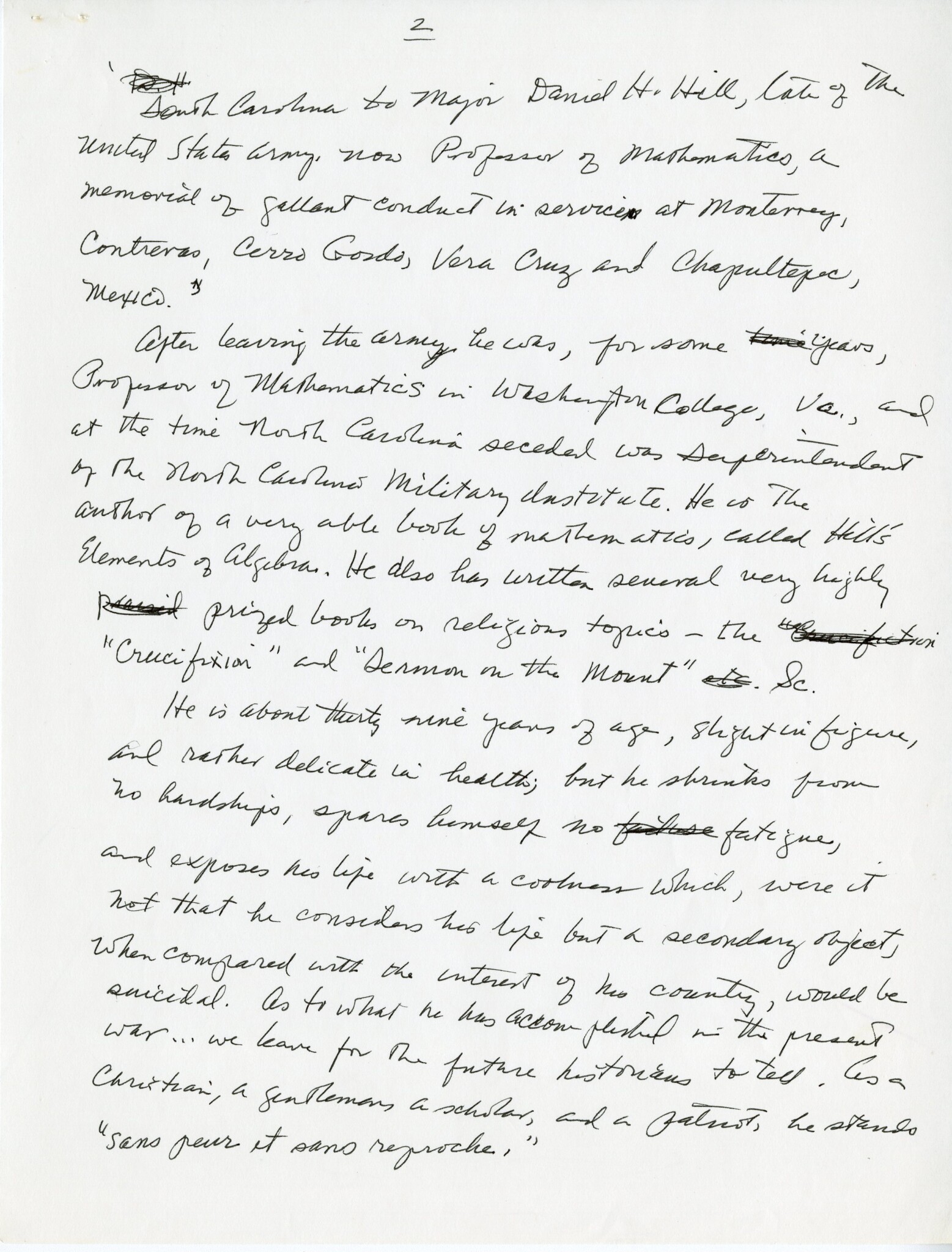

Two, who had experienced such brutalities, Rev. Elias Hill and June Moore, headed the emigration movement in York County. Born into slavery in 1819, Hill became handicapped at the age of 7, losing the use of both legs through a debilitating malady. Through hard word and thriftiness, he purchased his own freedom about 1840 (subsequent data shows that he was given his freedom due to his disabilities), and later the freedom of his wife. Having acquired a meager education from white children, he became a self-taught Baptist preacher and after Emancipation of his fellow men, he found himself in a leadership role and a target of the Klan. In May 1871, wrath fell on the handicapped preacher when he was accused of “political sermons” and having received a reply from Senator A. S. Wallace on his enquiry into relocating in Liberia.

A brutal beating only strengthened Hill’s resolve to seek peace in Liberia and encourage others to leave with him. In October 1871, under the auspices of the American Colonization Society, 136 emigrants left the Clay Hill area by train from Rock Hill to Baltimore. They sailed to Virginia on the Golconda, where other emigrants from South Carolina, Virginia, Georgia, Florida, and North Carolina joined them. After collecting household goods and other supplies to make the voyage and resettlement, they sailed from Hampton Roads to their new homeland on the Edith Rose.

***The Edith Rose link states, “166 passengers from Clay Hill traveling to Arthington Liberia.”

Two months after their arrival in January 1872, Rev. Hill wrote a letter to friends in York County announcing that except for the death of two infants, all 244 emigrants safely survived the 38-day voyage without incident other than seasickness. The ship had encountered numerous storms from November 7 to 25, sometimes so violent that tables, boxes, beds, provisions and other cargo rolled and tumbled across the ship, and passengers had to be tied in bed. Hill related that women and children who were in charge of preparing meals had a particularly hard time doing their tasks while trying to keep themselves balanced, and some times falling prostrate across the deck. So exhausted at the end of the day, they would collapse into their beds at nightfall. In spite of gales and rough seas, some days they put 520 miles behind them, while and on other days, when they reached the trade winds the Edith Rose was nearly stationary, progressing no more than just over 10 miles.

The Yorkville Enquirer reported on Feb. 14, 1878 – “The ship Azor is being refitted in Boston to serve as a transport ship to Liberia. The Azor was built at Boston in 1855 and was originally owned by S.W. Dabney. It was built of oak and is is registered at 397 tons with a carrying capacity of 300. Rev. F.B. Porter has purchased the ship and is soliciting passengers for the first voyage to Liberia.”

The Yorkville Enquirer reported on April 25, 1878 – “The ship Azor has sailed on its first voyage from Charleston to Liberia with 206 immigrants. The Azor is a former slave ship. The passengers included people from: Georgia, Charlotte, N.C., and from the S.C. counties of Lancaster, Abbeville, Clarendon, Charleston, Aiken, Edgefield and Barnwell.”

The Yorkville Enquirer on July 11, 1878 quoted the Charleston News and Courier – “which recently published as letter from Mr. A.B. Williams, a correspondent who accompanied the ship Azor from Charleston to Monrovia Liberia. The letter tells of the hardship, suffering and perils of the voyage. It describes the country of Liberia and we hope to print the entire letter soon.”

The Yorkville Enquirer reported on Aug. 15, 1878 – “The famous ship Azor has been sued by creditors for debts incurred during the trip to Liberia. The managers of the Liberian Emigration association are now loading the vessel with naval stores to take to Antwerp, by which they hope to pay the debts. It will be sometime before it can attempt another trip to Liberia.”

The Yorkville Enquirer reported on Nov. 13, 1879 – “The Liberian ship the Azor was sold at auction last Saturday in Charleston, S.C. for $2,950. It was purchased by the Exodus Association, it’s former owners.”

Throughout the voyage the emigrant’s faith sustained them when storms raged. At these times they lifted their voices in hymns and fervent prayers that God would spare their lives. Hill was exceptionally proud that the voyagers, using printed materials donated by the American Sunday School Union, organized a Sunday school on board. When weather permitted, Rev. Hill and Rev. Dillon of the Liberian Presbyterian Church always conducted Sunday services. Dillon had been a resident of Liberia since 1864 and had written a pamphlet on the people and land, and used to encourage emigration. These Christians maintained the strict observance of the Sabbath by doubling rations on Saturday so that no cooking was done on Sunday “that it might be kept blameless.”

Hill remarked on the kindness of Captain Alexander and the crew had shown the passenger by supplying medicine and offering medical attention to all in need. When the two infants died (two others were born on the voyage) the captain supplied the canvass wrappings appropriate for a sea burial and appointed the first mate to prepare the bodies. The captain personally performed the traditional services.

On December 14, at eight A. M., land was sighted near Grand Cape Mount. The next day they arrived at Monrovia at nine A.M. and docked at three in the afternoon. After reporting to the harbor master the captain prepared them to disembark the next day, Saturday, December 16. He arranged for the South Carolinians to land first which took the better part of the day for the boatmen to transfer the emigrants from the ship to shore. Due to Hill’s handicap, he was carried ashore in a hammock, and the 30 South Carolina families were taken to a reception center.

The next day, many attended services in a local Baptist church where Rev. Hill was invited to preach. A large group followed him back to the center where he was visited for several days by a throng of visitors consisting of Senators, Representatives, attorneys and ministers from all denominations.

Hill was taken with the city of Monrovia with its lush growth and fruit trees laden with oranges, lemons, pineapples, cassava, eddoes, sweet potatoes and coffee. He gave particular attention to the three volunteer “cotton trees” that grew near his door. He was told that these were 16 years old and grew with little tending. The least of these, he said, was 7 feet tall and contained 300 bolls even after much of the cotton had been picked.

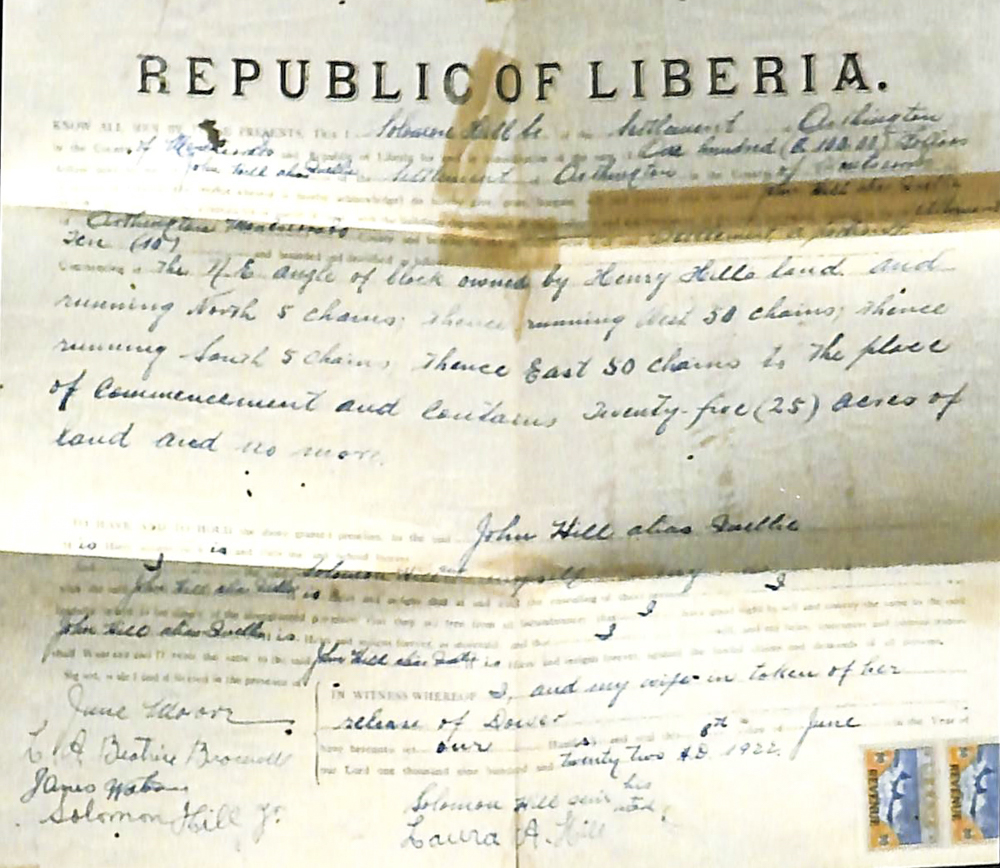

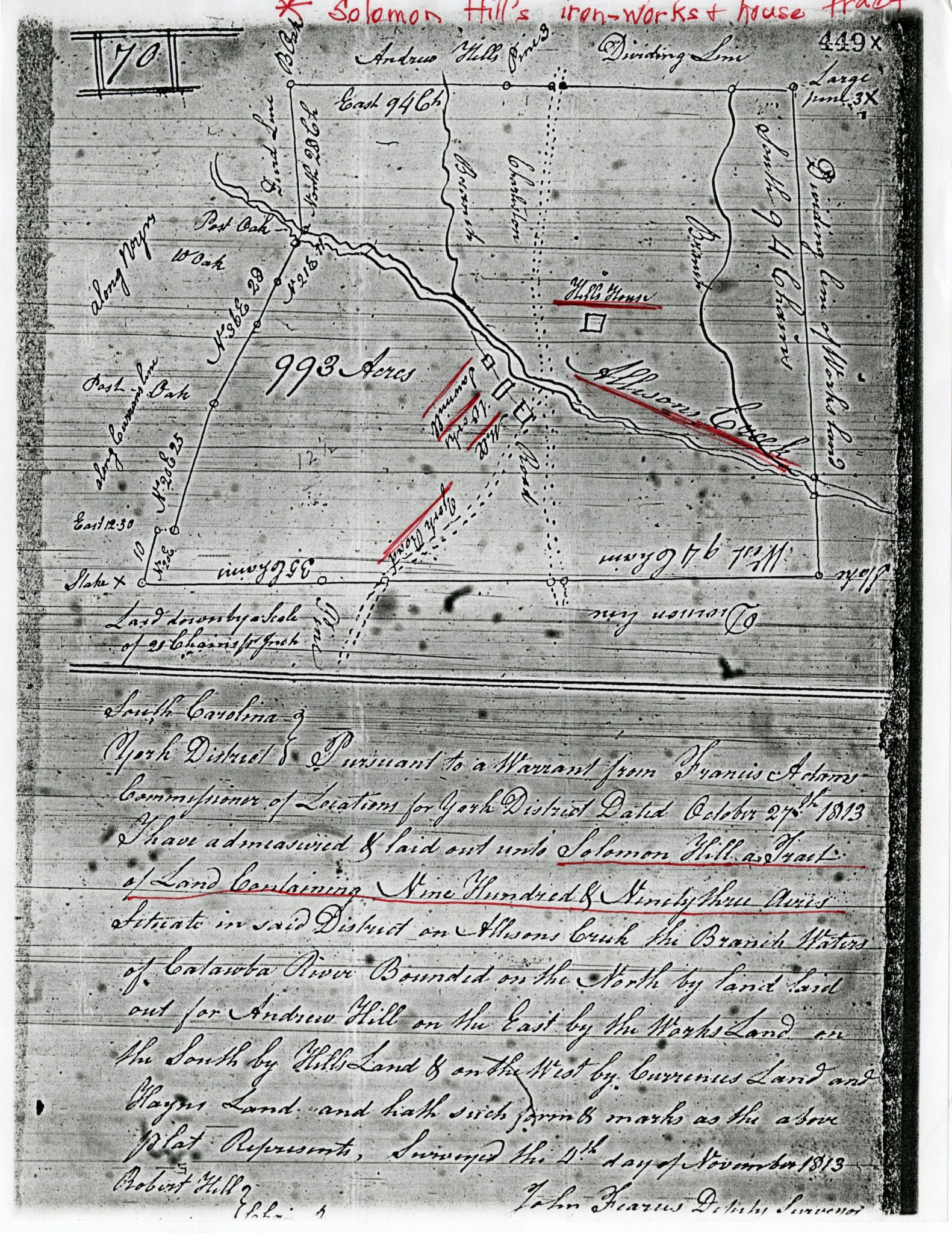

The business center consisted mostly of stone and brick buildings that housed a number of stores, all of which were doing a thriving business. The churches, he noted were “good edifices with steeples and bells.” Nevertheless, he saw that the city exhibited laziness and neglect; especially the back lots and streets were in poor condition and overgrown with weeds. He wrote, “It is only a place of trade and merchandize, and it’s inhabitants eat and dress and walk and talk and show off, legislate, plead cases, judge and cheat, and the rich live and delight in ease and luxury, and consequently hire the natives to wait on and work for them at low wages, while the latter class are also oppressed by heavy burdens.” The governmental affairs were in worse condition than the city. At the time, the President, Attorney General, Secretary of State, Secretary of the Interior, Speaker of the House, Secretary of the Republic, Probate Judge and some county supervisors were in jail. All were charged with robbery or defrauding the Republic of funds borrowed from Great Britain. The South Carolina colony sent six of its most respected men out to choose a site for their settlement. They favored the Arthington area that laid 20 miles into the interior, having good soil and timber forests. The Liberian government allotted a town lot and 25 acres of farmland to families; singles were granted a town lot and 10 acres. To obtain these grants, the settler agreed to have a certain amount of land cleared and a home constructed in six months. The American Colonization Society provided them with tools and river transportation. While the men cleared the land, their families lived in town.

As soon as the families were settled, like the Scots Irish of a century before, they sought to build churches and schools. The settlers from York County had farsightedness in providing an education for future generations, laying off a 200 site for a future college. The settlers had first hand experience in agriculture, which was revealed in the 1879 census of Arthington. At that time the settlement’s population was 292 and they had 463 acres in cultivation. This was remarkable as all the farm work was done by hoe and shovel in the absence of work animals. Since it took several years for coffee trees to mature, the settlers turned to raising ginger and other quick cash crops while the coffee fields matured.

Not only were these settlers good at fieldwork, they soon developed a broad business sense. A short time after Elias Hill and the York County settlers arrived in Liberia he wrote they were “preparing.to trade with the markets of the nations.” They knew too, that better prices could be had in the United States if they cut out the middleman and dealt directly with businessmen. One of the York County men sent word to a white dealer in Rock Hill that he would soon be able to provide him with all the coffee he needed.

The Yorkville Enquirer of Jan. 10, 1878 wrote, “Glenn’s Boarding House (the York Co Jail), begins the year with 28 regular boarders. Many are waiting for an interview with Judge Townsend, and five are there on a misunderstanding of the internal revenue laws.”

The Yorkville Enquirer of July 30, 1885 reported – “Clement Irons, who with her husband and family went to Liberia on the ship Azor, is in Charleston for a visit. She says most of the voyagers on the Azor have drifted to different parts of Liberia and have lost sight of each other. Her husband is doing well but will not return to America.”

Solomon Hill, a natural businessman found contentment in Liberia and wrote William Coppinger in 1872, “I am better satisfied than I ever was. I am only sorry that I did not come to Liberia the first I was freed.” Solomon and June Moore were destined to become true success stories. By 1887 they had formed the company of Hill & Moore, producing nearly 10,000 pounds of coffee that year. By the late 1890s they were doing more than $100,000 business annually.

As word of contentment and successes reached other African Americans living in America, other began to consider the move. In the fall of 1877, June Mobley of Union County came to York encouraging emigration. About 200 local African Americans gathered at the courthouse to hear Mobley who spoke for an hour. While he admitted he had never been to Liberia, he was planning to soon leave on an inspection tour and promised to return with a truthful report. In his argument favoring exodus, Mobley said he did not believe the black and white race could live together because the black man would always have to “take his place in the kitchen.” Speaking of his won experience, Mobley said he believed he had done all he could do to live at peace in the United States and could no longer remain contented and satisfied; therefore he favored immigrating to Liberia. After distributing literature that described Liberia in glowing terms, he asked willing participants to submit their names for a return to the land of their forefathers. The Yorkville Enquirer reported 26 had asked to be included.

Like the propaganda material handed out by Mobley, so was the material that placed into the hands of whites 50 years earlier encouraging migration to the west. Both exaggerated the new land where the settler could have contentment and wealth without hardship and perils of life. In truth, there were successes as well as utter failure. Similar to the experiences by white families who left South Carolina for a new life in the west, many Liberian emigrants fell on hard times and decided to return to their former homes. About a year after the York County settlers arrived in Liberia, several families left their land of promise to return home and more familiar surroundings; among these were the families of Francis Johnson, Minor Cathcart, John C. Moore, Madison Simril and the children of Bob Tate and Samuel McCollum. Some had little choice. Of a group of 370 emigrants in 1878, 29 died before reaching Africa and once settled only 60 survived the climate change, diseases and starvation. Perhaps another propaganda tool, the Weekly News in an 1890 article painted a promising picture of Liberia reporting it offered the settler better opportunities than any other part of Africa. According to the paper, Liberia was “the riches in resources of all West African countries and the only seat of an independent Christian State in Africa recognized by all the nations of the earth, the Negro republic is continually receiving colored emigrants from the United States adapted to the climate and skilled in the mechanical and agricultural industry.” The Weekly News boasted, “Here, then, will be a population prepared by centuries of training under Anglo Saxon influences, imbued with Anglo Saxon ideas.” In 1890 W. J. Massey, an emigrant to Mublenberg Mission on St. Paul’s River, and a prior resident of Lancaster County, wrote to the editor of the Lancaster Ledger, expressing his loathing of Liberia and plans to return. The Massey family had arrived in Cape Palmas in 1886, but finding it such a “poor place thought to try for a better one.” Still, they were no better off and complained, “Though this is a rich country–the soil is very fertile–yet we cannot plough and plant yearly on the same soil as we can in South Carolina. All the work is done here principally with the hoe, and cutlasses and bill hooks. I have not seen a ploughed furrow since I have been here, which will be three years the 25th of next month.”

According to Massey, the family had suffered ever since their arrival and soon began working to save for their passage back to the United States. Seeing their plight, a missionary, Rev. David A. Day, paid the passage for Massey’s mother to New York. The despondent emigrant closes his letter: “I will be more able to tell about this country when I get home, should I ever live to get there. I will also have a few of the curiosities of this country to show, and when I get there I never, I never will come here any more unless I am compelled to come, then they will have to hunt the bush to find me, and hunt it close.” Not only were individuals in turmoil, the country itself found difficulty existing. Conflicts over territorial claims resulted in a lost of land to Britain and France in 1885, 1892 and 1919. Liberia’s economy continued to decline during the late 1890s, finally faced bankruptcy in 1909. That same year a visitor to the Arthington settlement noted that 20 percent of the coffee farms had been abandoned and were overgrown. United States helped preserve the tiny country’s independence during the years of turmoil. A boost to the economy occurred when the Firestone Corporation leased large areas of land in 1926 and developed rubber plantations. Still, troubles continued to plague the republic. In 1930 a scandal erupted when the government, lead by President Tubman was found to be supporting slave trading. Always strongly influenced by the United States, Liberia participated in both world wars as an American ally. The Liberia Company, supported by American capital was organized in 1947 under an 80 year agreement to develop the country’s natural resources. Today, vestiges of the emigration from America can still be seen in Liberia through names, architecture and even food. Still an ally of the United States, the Liberian government, consisting of descendants of those freedmen from the United States, offers itself as a strategic point for American interests in Africa.

J.L. West – Author

LIBERIA’S ATTRACTION IN 1870s & ‘80s (Article by Louis Pettus, printed in York, a supplement of the Charlotte Observer, February 5,1994.)

In 1871 a group of York County blacks managed to gather up enough money to transport themselves and their families to the African country of Liberia. Liberia had been created as a haven for slaves in 1822 by the American Colonization Society, an offshoot of the abolitionist movement. The Liberian constitution was modeled after the U. S. constitution. The capital was named Monrovia for U. S. president James Monroe and U. S. currency became the official Liberian currency (until 1986). It appears that Solomon Hill was the leader of the blacks; certainly he was the most literate of the group. Other former York County blacks who prospered in Liberia were June Moore, Joe Watson, Scott Mason and George Black. In the summer of 1874, Solomon Hill wrote a letter to Sheriff Glenn in Yorkville. He told Glenn, “I have made one crop, and am nearly done planting another, and I know if a person will half work he can make a good living in Liberia.” Hill said that in the previous year he had raised rice, sweet potatoes and cassava. He had plenty for his own use and a surplus for sale. 22

Hill had added new crops and had good crops of corn and ginger. Ginger, he said, was a staple in Liberia and he had planted 50 pounds of ginger from which he expected his harvest to be 500 lbs. of dried ginger. He also had an orchard of 2,000 coffee trees, having planted his first 60 trees in 1872. Hill reported that nearly all of the former York county farmers had coffee trees laden with fruit that was worth 20 cents a pound in American currency. He enumerated the other articles produced by the colony: calico, tobacco, sugar, molasses, bacon, salted beef, flour, mackerel, chickens, eggs, turkeys, ducks and milk cows. Hill then boasted to Sheriff Glenn, “I am better satisfied than I ever was since emancipation, and am worth more than ever before. I have three good framed houses with shingle roofs, and neat board paling around my lot.”

He further reported that wild game was plentiful, including the sea-cow, deer, squirrels and monkeys. “I have seen as many as a thousand monkeys in one drove. The meat of this animal is highly prized as an article of food.” Hill also had a message for Colonel William H. McCorkle of Yorkville: .. within five years, if I live, I will be able to send him 4,000 pounds of Liberia coffee, of my own raising, and it is the desire of myself and friends to sell him our crops and ship direct to him.” There is no record that Hill was able to accomplish his goal of shipping his coffee to Yorkville but he wrote four years later that he had sold his entire coffee crop to Philadelphia merchants. The optimism of such letters as those written by Hill spread among other southeastern blacks who began making plans to emigrate to Liberia. The largest group set out in 1878. A number of the 1878 migrants returned to the U. S., unhappy with the conditions they found (for one thing the excellent soil and good crop-growing conditions described by Hill had been taken up by earlier settlers). Prices had gone up and most of the newcomers to Liberia lacked adequate money to invest. Besides that, the government was unstable and there was much ethnic strife. Word got around about overloaded ships where fever broke out. In one case, 23 passengers died on one ship bound to Liberia after the ship took on 206 passengers when it only had room, water and food for only 159.

Finally, unscrupulous travel agents and men posing as ministers of the gospel sold bogus railroad and steamship tickets. In 1886 a man posing as a Baptist preacher, J. C. Davidson, swindled a large number of Fort Mill blacks by selling them worthless tickets from Fort Mill to New York. This last episode ended what was called the “Liberian fever.” (Information courtesy of and from: YCGHS – The Quarterly Magazine, June 03)

Also access further data in the MORE INFORMATION link. And thanks to researcher, Mr. Spencer Simrill, Jr., additional information has been posted to R&R.

This article and many others found on the pages of Roots and Recall, were written by author J.L. West, for the YC Magazine and have been reprinted on R&R, with full permission – not for distribution or reprint!

Stay Connected

Explore history, houses, and stories across S.C. Your membership provides you with updates on regional topics, information on historic research, preservation, and monthly feature articles. But remember R&R wants to hear from you and assist in preserving your own family genealogy and memorabilia.

Visit the Southern Queries – Forum to receive assistance in answering questions, discuss genealogy, and enjoy exploring preservation topics with other members. Also listed are several history and genealogical researchers for hire.

User comments welcome — post at the bottom of this page.

Please enjoy this structure and all those listed in Roots and Recall. But remember each is private property. So view them from a distance or from a public area such as the sidewalk or public road.

Do you have information to share and preserve? Family, school, church, or other older photos and stories are welcome. Send them digitally through the “Share Your Story” link, so they too might be posted on Roots and Recall.

Thanks!

User comments always welcome - please post at the bottom of this page.

Click on image to pan and zoom.

Click on image to pan and zoom.

There were 161 people who departed with Rev. Elias Hill’s party. I have been trying to find if any of my relatives in the group survived; and if so, if they have any descendants who still live in Liberia. It is very difficult to ascertain this information.

Hi,

I am afraid we have little information on the migration and the subsequesnt return of many of those who departed with Mr. Hill. I would suggest you checking with the YC Archives in York, S.C., listed on R&R’s links menu. They may have printed information that would be helpful.

Wade@R&R