When Solicitor J. K. Henry took the floor he was at a definite disadvantage, but his clear and impressive voice captured the attention of everyone in the courtroom. He opened by recounting the events of a train wreck that occurred some years earlier in which new graduates of Erskine College were involved. “As the train was rushing along with the speed of the wind, it suddenly crashed through a bridge and down it went with its precious freight into the swollen water below. This was not ruin. It was only a wreck. Hope was left. The angels of heaven were there awaiting the arrival of those bright pure souls, and at once conducted them to the footstool of God to which they would soon be followed by the loved ones who had been left behind.

“Now I look upon another scene. Here is the house in which a woman, fair and fascinating lives, but with the wiles of the serpent. Here is the man Charles T. Williams. He tries to see her. After writing again and again, at last, he goes to her house. The lascivious Reese and his willing tool, Daniel Luckie, the partner of his sister’s shame, have been lying in wait for him. They come upon him suddenly. He flees up the street. They follow. A bullet goes crashing through his spine. This is not only a wreck; it is ruin. Ruin painted with a brush dipped in the blackest pigments to be dredged from the lowest depths of hell. Ruin without hope!

“Gentlemen of the jury, I stand on the bank of a turbid stream. I have known all along that the water was muddy. It is unpleasant to cross. As I have come close to it, I find it filled with driftwood, trash and filth. There is also floating down beautiful flowers, pearls and diamonds that have been placed there by the learned council to confuse my path. But gentlemen, I see on the opposite bank, a shining light. That light is duty. You and I have sworn to go to it. It devolves upon me to lead and you to follow. I am responsible only for myself, and not for you. Gentlemen, I am going to yonder light!”

Following Henry’s closing remarks, Judge Watts charged the jury and they were dismissed to began their deliberations. Nearly four hours later, just as the clock in the courthouse tower gonged nine, the jury returned with their verdict. Within ten minutes the judge, councils, sheriff and about one hundred spectators filed into the courtroom. The all-man jury found Reese and Luckie guilty with a recommendation of mercy and Ellen Anderson, not guilty.

As soon as the verdict was announced several men hurriedly left the courtroom and went to the rear of the courthouse where the prisoners would exit for jail. These sensation seekers wanted to be on hand in case of an attempted escape–and they were not

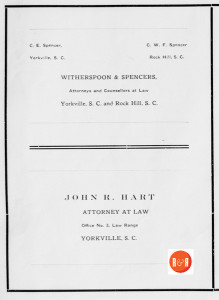

Image ca. 1912 – Courtesy of the YC Historical Society

Image ca. 1912 – Courtesy of the YC Historical Society

disappointed. Deputy Sheriff R. L. Scoggins led Reese out first, followed by his brother Frank with Luckie in tow. Seeing Attorney McDow, Luckie asked the deputy for a few minutes with his lawyer. The deputy and Reese went on ahead. Suddenly Reese broke from Scoggins the deputy and made a dash for freedom. Scoggins drew his pistol and shouted, “Don’t treat me that way. Hold up! Stop! Halt!” Not getting a response, the deputy coolly aimed and fired. Reese staggered like a drunk and fell into a gutter. The thrill-seekers rushed forward, but Scoggins turned on them and shouted, “Stand back or I will fill you full of lead!” Convinced Scoggins meant business there was a general scattering, some fleeing the scene entirely.

The Yorkville Enquirer reported on Jan. 6, 1892 – “Mr. R.L. Scoggins has been acting as deputy for Sheriff Crawford, but gave up the position last Friday and will return to his home near Hickory Grove to assist in managing his father’s plantation.”

Supported by Senator W. G. Finley and W. M. Stowe, Reese was led off to Kuykendal’s drugstore and then to Dr. Miles Walker’s office. A quick examination by Walker revealed the bullet had struck Reese just above the spinal column, in the thick portion of the skull. Realizing that removal of the slug would be difficult Walker sent for Drs. Andral Bratton and W. G. White. The physicians found that when the bullet hit Reese’s skull it broke apart and scattered. After two hours or more of probing they extracted half the bullet in three pieces. They concluded it would be best to leave the other pieces lodged in the neck muscles. After the physicians bandaged their patient he was led to the jail. On the way Reese said to Scoggins, “I wanted to die, and not desiring to take my own life, I ran in hope you would kill me. I wish you had killed me. I know I did wrong and I do not blame you, for you only did your duty.” Every town and community in York County was abuzz with the latest developments. When neighbor met neighbor on the streets, the trial, verdict and recent shooting was the main topic. Some pondered the possibility of mystical action and divine justice, noting that both Williams and Reese were shot on a Thursday night at about the same time, by the same caliber pistol near a Presbyterian Church and struck within three inches of the same spot while making escape.

Although Ellen Anderson was found not guilty, her troubles were not over. Robert Anderson, her estranged husband sued for custody of their six year old daughter, Foster, who was in his care. While waiting for her divorce papers to arrive from Georgia, before the proceedings began, depositions were taken so those from Georgia might return to their homes. On of those deposed was Mrs. S. G. Field, Anderson’s aunt who testified of her financial stability and was willing to raise the little girl. She stated she had six or seven thousand dollars belonging to her nephew for his child’s welfare and that she was worth fifteen thousand in her own right.

In the meantime, another case spawned by the Williams murder had been scheduled for 18 November. J. H. Riddle, administrator of the estate of Williams and on behalf of his widow, sued Marion Reese for $10,000 in damages. The law that provided for such suits was known as the “Lord Campbell Act” which provided support for the dependents of a slain man at the expense of the killer. Since the hearing would nearly be a repetition of the criminal case, Judge Watts was loath to wade into it again so soon. Therefore, it required very little effort for Reese’s lawyers to get a continuance until the April term.

Proceedings brought by Ellen Anderson began Saturday, November 21. A large number of people had crowded into the courthouse to hear the latest in the continuing saga. Robert Anderson charged his ex-wife was an unfit mother, that the case of the State against Reese proved she had been living an immoral life. His charges also included an accusation that the house in which she lived in adultery belonged to Reese. Ellen’s defense attorneys, Major James F. Hart, LeRoy F. Youmans and Thomas McDow, in order to derail the hearing, claimed the court did not have jurisdiction because neither she nor Robert were citizens of South Carolina. Robert Anderson’s attorneys W. B. DeLoach and Colonel Finley argued the court had full rights. Judge Watts’ ruling agreed with DeLoach and Finley ant the hearing continued.

Ellen denied she had ever lived in Reese’s house or ever had an affair with him; but an affidavit from J. D. Smith stated he sold the house to Mrs. Anderson but Reese made the payments. In her defense of her character, Hart submitted affidavits from the mayor of Demorest, Georgia that cited her mother and father, Doctor and Mrs. Patterson, were highly respected in the community. Robert’s council however produced seven affidavits from residents of Blacksburg who spoke of her immoral character. DeLoach read several affidavits from Georgia senators, representatives and other public officials giving Robert Anderson a resplendent reputation, integrity, sobriety and gentleness of character. The divorce papers showed Ellen and Robert Anderson were married in 1890 and separated two years later. They entered into an agreement that made Julian McCaney guardian of their daughter Foster. Robert Anderson waived all rights and placed more than two thousand dollars into the hands of McCaney for Foster, and contributed to her maintenance. Foster was to remain in her mother’s care until she attained the age of twelve, at which time she was to be placed in a boarding school of her parent’s choice. After her education was complete she was to be allowed to choose which parent she wanted to live with. Both parents had visitation rights. Robert testified that he and Ellen had remarried in the spring of 1894 at Blacksburg by Rev. W. S. Hamiter. His attorney argued that the divorce agreement was nullified upon their remarriage, and requested Anderson be given full custody of his daughter. Judge Watts ruled that he had no jurisdiction over Foster Anderson, but rather the chancery court of Georgia, and the child therefore must remain in the custody of Mrs. Anderson. Anderson would have to take his case before a Georgia court. Monday morning at eleven o’clock when Reese and Luckie appeared before Judge Watts for sentencing, Hart and Youmans presented their case for a new trial. Fifty to one hundred people filled the courtroom and gave their full attention to the four-hour proceedings. Hart submitted several affidavits from several members of the jury who stated that bailiff W. M. Stowe slept with the jurors and told them they were being watched by detectives hired by the defendants. Another jury member said Stowe warned them they must be careful, lest in the event they should be found guilty the defendants might be granted a new trial. George W. Moore stated he had been deputized to guard Mrs. Anderson at her arrest and it was then she told him that she “alone fired the shots that killed Charles T. Williams.”

Youmans presented to the court a list of alleged errors the law team believed warranted a new trial: (1) the indictment was defective in that it failed to sate the time and place of the killing, (2) the indictment alleged the assault upon Williams had been committed with a pistol, while the evidence presented showed death was caused by a bullet, (3) the court was in error for allowing Anderson to testify against his wife, (4) the court was in error in admitting into evidence the letter found on Williams’ body to be a letter to Mrs. Anderson when, in fact, she had never received it, (5) that the letters had been used to attack Mrs. Anderson before she was allowed to testify, and (6) that prosecution stated the letters were intended to decoy Williams to Blacksburg, but had failed to prove one sentence could be so construed. Youmans grasped at other flimsy reasons, complaining Solicitor Henry had inflamed public sentiment and prejudice, and caused spectators to applaud the prosecution three times.

Watts ruled that none of the alleged errors submitted warranted a new trial and called for the prisoners to be brought before him for sentencing. Without any outward sign of agitation Watts spoke to Reese and Luckie: “I am always sorry for anyone in your condition. You have been tried for the murder of Charles T. Williams. The jury said that you are guilty, and in my opinion the verdict is sustained by the facts. Your two are the murderers. You, Mr. Reese, have led an irregular and vicious life, and you are now reaping as you have sown. You, Daniel Luckie, I regard as the weaker vessel. The testimony satisfies me that you have only been a servile tool of the stronger mind of Marion Reese. There is no doubt in my mind that Mrs. Anderson is morally responsible for the death of Charles T. Williams, although I do not believe that he came to his death, as she say, at her hands. It was at the hands of you, Marion Reese and you Daniel Luckie, but to my mind the woman is responsible for your present condition–the sacrifice of your liberty for the balance of your day. But I do not wish to be unnecessarily cruel in my remarks. They can be of no benefit to you now. The sentence of the court is that you, Marion R. Reese, and you, Daniel F. Luckie, be confined in the state penitentiary, at hard labor, for the balance of your natural lives.”

We would think that the curtain had fallen on the drama that opened nine months earlier on the night of 6 February, but Reese and Luckie had another scene to play out. Just a few days over a year since Williams had been murdered, both convicted men escaped from the Yorkville jail with twenty others. A month later York County Sheriff Logan received a telegram from Tennessee Chief of Police P. H. Dennison: “My deputy has captured a man answering the description of M. R. Reese and I claim the reward [of $700].” Logan instructed Dennison to examine the man’s back for a scar and his neck for a piece of a bullet lodged under the skin. A few hours later Dennison wired back: ” the man captured was not the man wanted.” Sheriff Logan’s hopes of retrieving his prisoners fell. Then, another telegram was received from Dennison; this one was quite mysterious: “My deputy won’t let me see the man.” One thing seemed certain, someone in Tennessee is eager to get the reward.

Logan sent Dennison a picture of Reese along with a full description. There must have been grave disappointment in both Tennessee and South Carolina when Logan received a letter from Dennison the following Monday saying the man in custody was not Reese. The mystery seemed to have concluded; except that another letter was placed in the sheriff’s hand that gave a new twist to the story. The second letter was from James Alexander, Dennison’s deputy who wrote that he and others had Reese in custody and needed instructions. We are not sure how this situation played out, but we know for sure that Reese and Luckie were not captured. A good drama is always better when it ends with a mystery; and this story leaves us hanging. Recently the writer was in touch with Martin Saxon of Australia who is also puzzled by the whereabouts of these two men. He said the judge believed Marion Reese had gone to South Africa and Daniel Luckie to South America. Mr. Saxon followed up on a lead that put Reese in Australia, but that lead came to a dead end. The Australian researcher now doubts that either man left the United States, but found a place to live out their lives in freedom.

J.L. West – Author

This article and many others found on the pages of Roots and Recall, were written by author J.L. West, for the YC Magazine and have been reprinted on R&R, with full permission – not for distribution or reprint!

Please enjoy this structure and all those listed in Roots and Recall. But remember each is private property. So view them from a distance or from a public area such as the sidewalk or public road.

Do you have information to share and preserve? Family, school, church, or other older photos and stories are welcome. Send them digitally through the “Share Your Story” link, so they too might be posted on Roots and Recall.

Thanks!

User comments always welcome - please post at the bottom of this page.

Share Your Comments & Feedback: