The Abbeville Press and Banner reported on May 27, 1891 – “Mattison and Wardlaw now have a soda fountain and can now serve a cool drink on any kind.”

Also in this issue – “Mr. J.W. Tolbert’s new residence will soon be completed.”

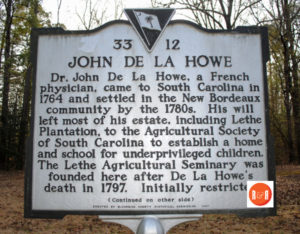

People came to the area that is now McCormick County, South Carolina, around the middle of the eighteenth century to claim land bounties. In 1756, five families of Calhouns pioneered the Scots-Irish Long Canes settlement. French Huguenots established the New Bordeaux colony on Little River in 1764, and German

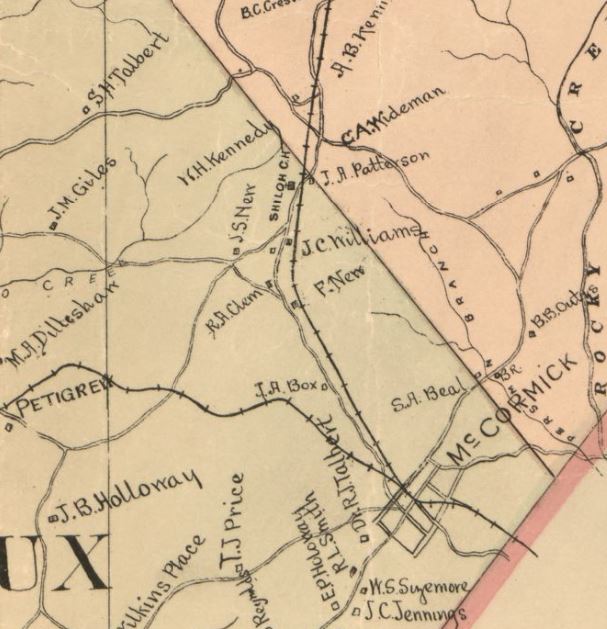

Bullock, W. P, and Paul L Grier. Official topographical map of Abbeville Co., South Carolina. [S.l.: P.L. Grier, 1894, 1895] Map. Retrieved from the Library of Congress

Tobacco was the first real money crop. By the late 1700s area farmers were increasingly growing wheat for flour. Early commercial centers in the county were Vienna on the Savannah River, Calhoun Mills on Little River, Liberty Hill on Barksdale Ferry Road, and Parks’ Store (now Parksville). The invention of the cotton gin by Eli Whitney in 1793, and then Augusta, Georgia inventor Hogden Holmes’ much-improved gin in 1796, clinched the production of short staple cotton to the area. There was an almost instant shift to cotton by farmers for a money crop. Cotton was being harvested for export by 1802, and became the standard measure of an individual’s wealth.

The “Golden Age” of the antebellum era lasted from the late 1810s until 1860.

Production increased and there was great prosperity. Land remained cheap. Farmers virtually abandoned subsistence farming for cotton. The soul of the South became wrapped up in the pursuit of growing cotton. A generation of its young men was lost in the War for Southern Independence. In 1860, South Carolina was the third richest state in the Nation. After the war, in which 35% of its young adult white male population died, (as compared to 1.5% in World War II), it was among the poorest. Of those who returned, hundreds were permanently disabled. Following the war, Southerners suffered for twelve long years during Radical Reconstruction. The Southern economy was in shambles. Widespread debt was rampart. Scalawags were placed in charge of county governments. Countless farmsteads were lost to the tax collector’s gavel. Patrols of Union soldiers were stationed at county seats – Abbeville, Edgefield. Military rule ended with the election of Wade Hampton as governor of South Carolina, this brought about in a back-room deal by which Rutherford B. Hayes was elected president.

The post-antebellum era brought about a new system that totally changed the face of Southern agriculture. Land owners subdivided their land holdings into smaller farms. White yeoman farmers tried to hold to ownership of their small farms. The new system of tenants and sharecroppers worked something like this: A farmer and his family would agree to work a tract of land for a certain period of time and share the profits. When the crop was sold in the fall, the landowner would claim his share, usually 50%, and the sharecropper would be given the

The historic Long Canes ARP Church – Image taken by R&R in 2015

other half, after expenses were deducted by the landowner for a customary credit advance to cover the sharecropper’s living expenses during the crop year. Tenant farming differed in that the tenant simply leased the land at a set amount regardless of the crop yield. Tenancy tended to be less exploitative than sharecropping.

By 1880, approximately 90% of the crops produced were grown on small farms of thirty to fifty acres. Sharecroppers or tenants and their wives and children worked half of those farms. Cotton production was twice what it had been in 1860 with sharecroppers and tenants working nearly half of the farms – a trend that continued to grow until the 1940s. The system of landowner, tenant, and sharecropper had been firmly entrenched. McCormick County was destined to remain an agrarian county yoked to “King Cotton” well into the mid-twentieth century. There were more than 2500 farms in McCormick County in 1920. Generations of cotton production with few efforts to maintain fertility reduced the natural productivity of the soil. The cost to the environment in loss of topsoil through erosion, siltation of streams, and consequent flooding was immeasurable.

Out migration brought about serious population decreases in McCormick County – from an estimated population of 20,000 people when the county was formed to 16,444 in 1920, to 11,471 in 1930, to 10,367 in 1940, and to 9,577 in 1950.

In order to place into proper context the surge of out migration from McCormick County during the decades of the 1920s, 1930s and 1940s, it is necessary to look at the whole picture, taking into consideration the following five situations.

1. Following the end of World War I (in 1918), cotton prices dropped like a rock, which quickly induced out migration primarily in the county’s majority black population. The steady stream of poor black sharecroppers and tenant farmers accelerated into a mass exodus during the 1920s. Blacks wanted money and a better life and they wanted to live in the city. Large numbers migrated to Northern cities.

The John De La Howe school has been an important part of McCormick County’s history.

2. The boll weevil, only ¼ inch in length, that attacked the cotton plant introduced yet another disastrous problem. It reached McCormick County in 1919 in token numbers. By 1921 it was primed for destruction as it attacked that year’s cotton crop with vengeance. Farmers ginned only 4,892 bales of cotton as compared to 16,410 the previous year. 1922 was worse as the weevil wreaked disaster. The county produced 1,723 bales of cotton in 1922. The economy took a huge hit. Businesses failed. Banks closed. Out migration accelerated.

3. The Great Depression that arrived in 1929 devastated the American people in the decade of the 1930s. As the Depression deepened, it produced conditions in McCormick County that were among the worst in the nation. The suffering of the farm families produced reverberations throughout the county’s economy.

Many children went to bed hungry and were reduced to using gunny sacks and flour bags to clothe themselves, and many were also barefooted.

A 1935 survey taken over entire McCormick County indicated that 70% of farmers were non-land owners. When race is taken into account, 43% of white farmers were cash renters, tenants, sharecroppers, or squatters farming on land they did not own. In contrast, 91% of black farmers cultivated land not owned by them. Only 18% of farmers owned

automobiles – luxuries most of them could not afford. Only 3% of farm families owned radios.

The survey indicated housing quality as a visible indicator of standard of living. 59% of houses surveyed were rated as “poor.” Only 1% of houses surveyed had indoor toilets. 75% of the farm houses included an outdoor privy. The remaining families made do without sanitary facilities entirely. Women and children more often cultivated gardens and tended chickens and cows and hogs. Pork meat was a principal food source. Some families opted to sell pork hams to the well-to-do in town to provide cash for the family. Farm families supplemented their food supply with wild game – rabbits, quail, possums, squirrels – and fish from the streams.

The author recalls a widow woman with several infant daughters living in the Cedar Hill community roasting wild song birds that she popped with a BB gun for serving to her hungry family. Another family fried hawks, the father claiming that the meat was as good as chicken. Every farmstead produced corn; many also produced oats, wheat, and barley. These crops provided feed for vital farmstead animals – mules, horses, cows, and hogs – and for poultry.

With no electric service in rural areas the lack of refrigeration in homes was keenly felt. In 1941, less than 5% of the rural population of McCormick County had electric service. Only a few rural families owned Delco power plants that supplied 32-volt DC electricity for individual homes and farm buildings. Without the luxury of cold storage for food, among the poorer families the seasonal scourge of pellagra commonly emerged each year after a prolonged winter diet short of

B vitamins. The high rate of hookworm infestation, often reaching 30% to 40% was linked directly to the lack of indoor bathrooms. Country schools were without modern lighting and sanitation facilities.

McCormick Commission of Public Works provided a water system within the Town of McCormick only. Rural citizens used springs, streams, and dug wells. Economic troubles and weather continually plagued county officials as they struggled to perform adequate maintenance throughout the county on roads (mostly unimproved dirt) and bridges utilizing convict labor

The decades of the 1930s and the 1940s witnessed striking numbers of whites and blacks migrating out from the county. Migrant whites moved south and west but particularly they found jobs in cotton mills in nearby towns. Blacks continued to relocate to Northern cities.

4. Initially, the U. S. Forest Service planners launched a massive conservation-oriented land purchase plan in December 1934, to buy up 431,000 acres of farmland determined sub-marginal by that agency and to shift it from erosion-inducing row crop production to timber land In its original context, the Forest Service contrived to buy up as much as 80% of the total area of McCormick County for inclusion of its National Forest.

At first most politicians and community leaders expressed strong support. But, in a newspaper “letter to the editor” blitz, Hugh C. Middleton of Clarks Hill almost singlehandedly led a movement to oppose the Forest Service plans. Critics rallied around Middleton’s fight claiming that such a massive land purchase plan would lead to erosion of the already weakened tax base since counties had no authority to tax federal property. Opponents reasoned it might force the demise of McCormick County.

In a public meeting held in McCormick on April 28, 1935, an investigative committee was appointed by citizens to gather information about the project. A month later, citizens gathered again to hear the committee’s findings. Citizens appointed a delegation to request that the Forest Service cease to purchase land until the agency had properly addressed local concerns. As a result of the opposition, the Forest Service agreed to limit its acquisitions to key areas within boundaries of units already purchased. Ultimately, the Forest Service would own 21% of McCormick County’s land area.

5. Persistent rumors of the approaching Clarks Hill Dam project produced a troubling affect within the beleaguered farm population in the affected areas. During the early 1940s, even before actual acquisition of the lands took place farm families began to move out, especially renters, tenants, and sharecroppers, who had little to lose, to seek new occupations and homes. Government acquisition of land for Thurmond Lake decreased the land area of McCormick County by 20%. Combined with the 21% already acquired by the U. S. Forest Service, the Government now held a whopping 41% of the land area of McCormick County.

[Written and submitted to R&R by Author and Historian, Mr. Bobby Edmonds of McCormick, S.C.]

Stay Connected

Explore history, houses, and stories across S.C. Your membership provides you with updates on regional topics, information on historic research, preservation, and monthly feature articles. But remember R&R wants to hear from you and assist in preserving your own family genealogy and memorabilia.

Visit the Southern Queries – Forum to receive assistance in answering questions, discuss genealogy, and enjoy exploring preservation topics with other members. Also listed are several history and genealogical researchers for hire.

User comments welcome — post at the bottom of this page.

Thomas Lindsay (born 1728) came with his Lindsay family members to the 96th district, later called Abbeville, now McCormick. My ancestor Thomas came with his wife Elizabeth, daughters, Agnes and Elizabeth and two sons Thomas (my ancestor) and James. They came on the ship Earl of Hillsborough from Belfast, North Ireland Christmas Eve 1766 and arrived in Charleston, South Carolina in February in 1767. Thomas, the elder was granted 400 acres (from the King) at Long Cane being in Troy, South Carolina. There is a creek near his 400 acres, it is called Linkay Creek,. I believe the name is more than likely Lindsay. Thomas Lindsay 400 acres now belongs to the Sumter National Forest.