City Directories and History: JOHN RUTLEDGE HOUSE

Constructed circa 1763; altered circa 1853, 1890; rehabilitated 1988-89

“When constructed, this building had a Georgian facade that lacked the ornate iron-work and Greek Revival details employed in the design today. John Rutledge, “Dictator” and governor of South Carolina during the Revolution, built this house before 1770 for his wife Elizabeth Grimke. Rutledge went on to serve as an associate justice of the U.S. Supreme Court and held a brief,

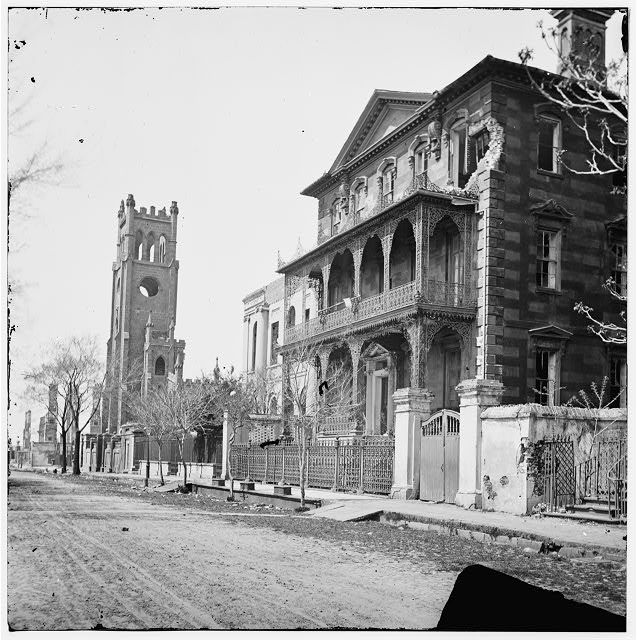

Note the devastation resulting from the Federal bombardment of Charleston in Dec. 1861. Courtesy of the Library of Congress.

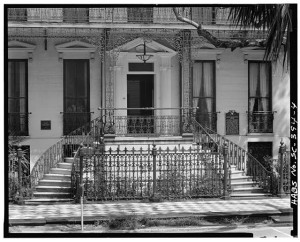

unconfirmed term as chief justice before illness hastened his demise in 1800. The house passed through a number of different owners from 1790 until 1835, when it served briefly as the residence of Charleston’s first Roman Catholic bishop, Rev. John England. Thomas Norman Gadsden, a wealthy slave trader and landowner, was responsible for the renovations of the Rutledge House in 1853 and added terra cotta window lintels to the exterior as well as the intricate cast-ironwork, utilizing R H. Hammarskold as his architect. Hammarskold, a native of Sweden, was then working on the new statehouse in Columbia. The cast-ironwork, executed by German-born blacksmith Christopher Werner, includes palmetto and eagle designs in the end columns as well as acanthus and anthemion motifs popular in the late-Greek Revival period. In the late- nineteenth century, the house served as the residence of Mayor R. Goodwin Rhett. Supposedly Rhett entertained President William Howard Taft here during his visit in 1909, during which William Deas, the butler, introduced his now-famous she-crab soup.”

Information from: The Buildings of Charleston – J.H. Poston for the Historic Charleston Foundation, 1997

“John Rutledge (1739-1800) built this house as a wedding gift for his bride, 19-year-old Elizabeth Grimke, in 1763. Rutledge was a member of the South Carolina Assembly, the Stamp Act Congress, the Continental Congress and the U.S. Constitutional Convention. He was President of

South Carolina between 1776-1778 and Governor of the State between 1779-1782. Rutledge also served as Chief Justice of South Carolina and Associate Justice of the U.S. Supreme Court. In the second floor drawing room, now the Signer’s Ballroom, Rutledge, who chaired the drafting committee, wrote several iterations of the Constitution of the U.S. He later signed the document with the other founding fathers. In 1791, George Washington had breakfast with Mrs. Rutledge during his Presidential visit to Charleston. Rutledge is buried in St. Michael’s Churchyard. Sometime after 1790, the property was acquired by Gen. John McPherson, a Revolutionary Patriot and a prominent figure on the South Carolina turf. He was among several horse breeders credited with improving the state’s stock of horses and maintaining the high standard of racing. This made the South Carolina Jockey Club famous in the annals of racing during a period when it was considered the sport of gentlemen.

The house was sold in 1836 to the Right Rev. John England, Roman Catholic Bishop of Charleston, whose executors later sold it in 1843. Ten years later it was acquired by Thomas Norman Gadsden, a real estate broker and slave trader. In 1853, Gadsden engaged Swedish architect P.H. Hammarskold to remodel the house. Hammerskold added terra cotta window cornices and the iron balcony, posts, curving step rail and fence to the property. He also designed the two-story brick kitchen with Gothic arched windows. The elaborate ironwork, a combination of wrought and cast iron, is attributed to Christopher Werner and depicts the Federal Eagle and S.C. Palmetto tree as a tribute to Rutledge’s service in federal and state governments. During the Civil War, the Rutledge House fortunately survived a great fire that destroyed the building next door where the Articles of the Secession were signed, though it took a direct hit from a Union cannon during the siege of Charleston.

Arthur Barnwell acquired the property from Gadsden’s family in 1885. Barnwell re-modeled the interior, and installed eight Italian marble mantelpieces from England and parquetry floors made from three kinds of wood, in a design copied from European palaces. It is said the carpenter Noisette took eight years to install the floors. Barnwell sold the property in 1902 to Robert Goodwyn Rhett, who was Mayor of Charleston, president of the Peoples Bank and one of the developers of North Charleston. During Rhett’s ownership, William Howard Taft, U.S. President and Chief Justice, was a weekend guest several times.

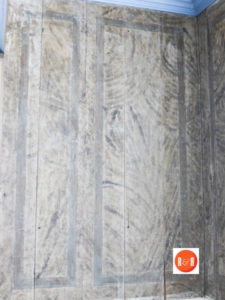

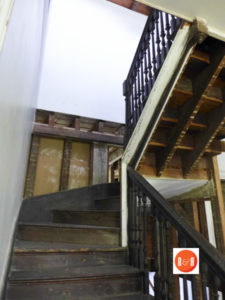

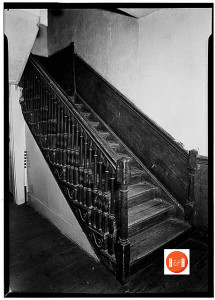

Tradition says that during the Rhetts’ residence, their butler, William Deas, invented she-crab soup.The Rutledge House served as a residence, offices and The Gaud School for more than 100 years, after which it briefly sat vacant. In 1989, a major restoration was undertaken to restore the inlaid floors, plaster work and staircase and return the house to its former glory. Additionally, an array of modern conveniences were added to transform this historic structure into an elegant, beloved bed and breakfast in Charleston.” (John Rutledge House; Ravenel, Architects, 240, 242-243; Smith & Smith, Dwelling Houses, 254-255; Stoney, This is Charleston, 16; Barry, Mr. Rutledge, passim; Wallace, 256-257, 290-293, 339; Rosen, 129, 143; Ravenel, Charleston, The Place and the People, 161, 172, 225-227, 255, 319-320, 400; Stockton, DYKYC, March 24, 1975; Nielsen, DYKYC, Feb. 10, 1936; Rhett, Gay, Woodward & Hamilton, 2-3.) – CCPL

John Rutledge, a signer of the Constitution and wartime Governor of South Carolina, 1779-1782, lived at 116 Broad Street from 1763 to 1800. Rutledge was one of the foremost lawyers in South Carolina. He opposed the Stamp Act and in the Stamp Act Congress of 1765 he was chairman of the committed which wrote the memorial and petition to the House of Lords. He was a member of the First and Second Continental Congresses and helped write the South Carolina Constitution of 1776. Rutledge served as Governor from 1779 until 1782. In 1784 he began his judicial career with election to the chancery court of the state and from 1784-1790 also sat in the state House of Representatives. In 1789 Washington appointed Rutledge Senior Associate Justice of the U.S. Supreme Court and he held this office until February 1791, when he resigned to become Chief Justice of South Carolina. Rutledge died in Charleston on July 23, 1800. The house is a large three-story over elevated basement brick house with a slate covered roof, a pair of large brick chimneys set in either side wall, and an elaborate two-story cast and wrought iron porch on the front elevation. The first two stories were built by Rutledge in 1763 and the third floor was added by Thomas M. Gadsden in 1853. Listed in the National Register November 7, 1971; Designated a National Historic Landmark November 7, 1973.

(Courtesy of the SC Dept. of Archives and History)

*** The S.C. Artisans Database lists on Peter H. Hammarskold, age 35, in 1850, working as an architect in Charleston, S.C. Also see link this page to the S.C. State House Building which he was also working on.

There was a rigid hierarchy in Carolina society: rice planters were considered the cream of the crop, followed by the sea-island cotton planters and inland cotton growers. As in England, land went to the oldest son, and the younger sons went into professions and would, hopefully, marry into ownership of a plantation. Tradesmen were at the very bottom of the social scale. This social convention affected Eliza Lucas Pinckney’s family. Her granddaughter Harriott Horry did not wish to marry any of the eligible local rice planters and eloped with Frederick Rutledge, son of Chief Justice John Rutledge, one of South Carolina’s most accomplished statesmen. Rutledge had a long and distinguished career and enjoyed the friendship of many of the founding fathers. During the Revolution, Rutledge worked for the southern Continental army. As president of South Carolina, he was able to restore order to the state while in office. He held numerous elective offices and served as a delegate to the First and Second Continental Congresses and the Constitutional Convention.

He served as chief justice of the United States Supreme Court and the South Carolina Supreme Court. The chief justice was also known for his fine wine cellar and was proud of his ability to drink two quarts of Madeira a day. Toward the end of his life, Rutledge was deeply in debt and threatened with the loss of his entire fortune. Stricken with gout, overwhelmed with the enormity of his debt and mourning his wife’s sudden death, he spiraled into a deep depression. He attempted suicide.'” It was kept as quiet as possible, and nobody in the Pinckney-Horry family ever dreamed that tragic predisposition would affect them many years later.

The seventh child of Harriott Horry and Frederick Rutledge was John Henry Rutledge, grandson of the chief justice. His sensitive nature and loving ways made him the darling of the family. He hunted the land and charmed his mother and grandmother with his escapades. He was an accommodating child who never caused a bit of trouble—that is, until he fell in love with a pharmacist’s daughter.

It was understood at Hampton that planter families were to marry within their own social class. The matriarchs could not convince John Henry that he must relinquish his affections, nor would the girl’s father permit his daughter to marry into a proud family that would consider the bride even less desirable than one of their own enslaved black servants. Thwarted on every side, John Henry took to a rocking chair in his upstairs room, and a deep depression settled in. He rocked and he rocked and he rocked. One day, a shotgun blast startled the occupants of the house. John Henry’s mother and grandmother dashed upstairs only to see life seep out of his bleeding body. Unable to bury a victim of suicide in the family plot, John Henry’s body was interred by the stairs of the river side of the mansion. It is said that the chair continued to rock until the day it was removed from the house, and family servants claimed that the blood that dripped from his bleeding body bubbled back every time it was scrubbed off the floorboards. (Courtesy of author and historian, Peg M. R. Eastman – Hidden History of Old Charleston, History Press – 2010)

Other sources of interest: Charleston Tax Payers of Charleston, SC in 1860-61 and the Dwelling Houses of Charleston by Alice R.H. Smith – 1917 The HCF may also have additional data at: Past Perfect and further research can be uncovered at: Charleston 1861 Census Schedule or The Charleston City Guide of 1872Charleston Library Society

Stay Connected

Explore history, houses, and stories across S.C. Your membership provides you with updates on regional topics, information on historic research, preservation, and monthly feature articles. But remember R&R wants to hear from you and assist in preserving your own family genealogy and memorabilia.

Visit the Southern Queries – Forum to receive assistance in answering questions, discuss genealogy, and enjoy exploring preservation topics with other members. Also listed are several history and genealogical researchers for hire.

User comments welcome — post at the bottom of this page.

R&R HISTORY LINK: SCHS Mag. article; “A Short History of A.E.O.C. via Thomas P. Rutledge” by J.P. Beckwith, Jr.

Please enjoy this structure and all those listed in Roots and Recall. But remember each is private property. So view them from a distance or from a public area such as the sidewalk or public road.

R&R HIDo you have information to share and preserve? Family, school, church, or other older photos and stories are welcome. Send them digitally through the “Share Your Story” link, so they too might be posted on Roots and Recall.

Thanks!

IMAGE GALLERY courtesy of the Library of Congress – HABS Collection

floor, built by Noe Serre, a Huguenot settler. The one-and-one-half story frame building on raised brick foundations was 40 feet long and 34 feet deep, and had two interior chimneys. In 1757, the plantation came into the possession of Daniel Horry through marriage, and shortly thereafter he more than doubled the size of the original house. A second full story was added and extensions made to both ends, bringing the structure to its present size. The present hipped roof, with two dormers in front and rear, was built over the entire house, and each new wing had an interior chimney. In 1790-91, the south façade assumed its present unified appearance, when a six column wide giant portico and pediment were added across the center portion of the original house. Rosettes, panels, and flutings adorn the frieze of the portico, and the pediment contains a circular window with four keystones. Listed in the National Register April 15, 1970; Designated a National Historic Landmark April 15, 1970. [Courtesy of the SC Dept. of Archives and History]

floor, built by Noe Serre, a Huguenot settler. The one-and-one-half story frame building on raised brick foundations was 40 feet long and 34 feet deep, and had two interior chimneys. In 1757, the plantation came into the possession of Daniel Horry through marriage, and shortly thereafter he more than doubled the size of the original house. A second full story was added and extensions made to both ends, bringing the structure to its present size. The present hipped roof, with two dormers in front and rear, was built over the entire house, and each new wing had an interior chimney. In 1790-91, the south façade assumed its present unified appearance, when a six column wide giant portico and pediment were added across the center portion of the original house. Rosettes, panels, and flutings adorn the frieze of the portico, and the pediment contains a circular window with four keystones. Listed in the National Register April 15, 1970; Designated a National Historic Landmark April 15, 1970. [Courtesy of the SC Dept. of Archives and History]