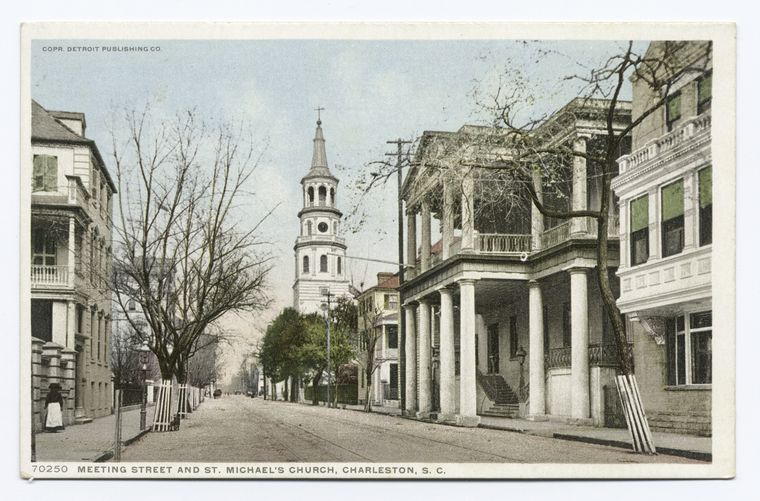

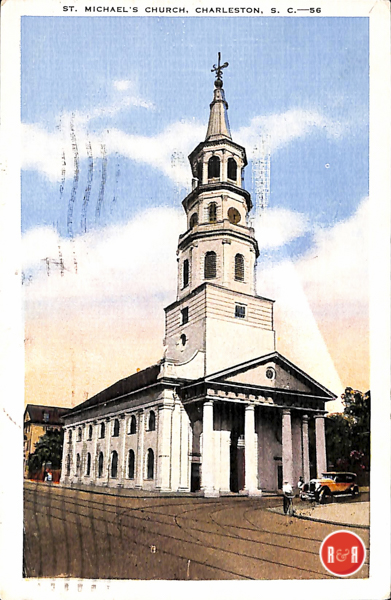

” A fine Geogian Palladian church nearly destroyed by the Union forces during the Civil War.”

80 Meeting Street

City Directories and History: Saint Michael’s Church graphically illustrates the great increase in wealth and power in the Southern American colonies by the middle of the eighteenth century. Although possibly designed by an unknown architect and built by Samuel Cardy between 1752 and 1761, St. Michael’s shows a keen awareness of its architectural prototype by the English architect, James Gibbs’ Saint Martin-in-the-Fields (1726). The two-story structure of Saint Michael’s is of brick, stuccoed over, and radiating its brilliant white paint skin in the subtropical Carolina sun. The classical portico dominates tremendously the Broad Street front, and together with the steeple, dominates the whole exterior. It is a giant two-story portico with Tuscan columns, the first

Image courtesy of: The Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Division of Art, Prints and Photographs: Photography Collection, New York Public Library. Collection of images and prints of Charleston, S.C.

American colonial church to have the giant portico. The columns are of stuccoed pie shaped brick, the roof of slate, with a slight outward bend near the eaves, and the roof of the steeple of cypress sheathed in copper. The balustrade at the arcade level of the steeple was carved by one of Charleston’s foremost colonial woodworkers, Thomas Elfe. The two-story seating arrangement of the interior is articulated at the exterior, by the rows of round arched windows. Each window is surrounded by the Renaissance rustication that came to be known in England as the Gibbs surround, in France as Serlions. Pairs of windows are visually separated from others by a two-story pilaster, supporting the undecorated entablature. Listed in the National Register October 15, 1966; Designated a National Historic Landmark October 9, 1960. [Courtesy of the SC Dept. of Archives and History]

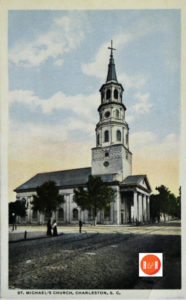

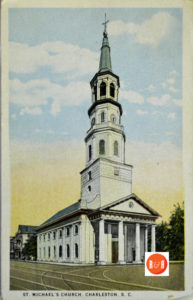

ST. MICHAEL’S CHURCH

Constructed 1752-61; interior completed 1772; renovated 1818, 1887, 1905; restored 1993-94; Samuel Cardy, contractor; Humphrey Sommers, mason; Henry Burnet and Anthony Forehand, carvers, “St. Michael’s Church has long been considered one of America’s most sophisticated colonial church buildings. It was begun in 1752 following an act of the Assembly for building a new parish church on the site of the first St. Philip’s. Whatever the origin of the plan and the stylistic relationship between this building and the London city churches designed by Sir Christopher Wren and James Gibbs, St. Michael’s cannot be tied to one source or definitively attributed to a single architect.

R&R HISTORY LINK: SCHS Mag. article; “Letter from Henry Ward Beecher” from the Bennett-Campbell Papers

The exterior, except the Tuscan portico, was essentially complete by 1756. The steeple, which rises 186 feet, is today surmounted by a seven-and-a-half-foot weathervane with a gilt ball, an 1820s re-placement of an earlier ball and dragon vane gilded by the artist Jeremiah Theus. Building commissioners’ records reveal that Henry Burnet, a house and ship carver from London who died in 1761, carved the details for the steeple and interior details such as the capitals of the gallery columns, the narthex stair brackets, and the pulpit. The base and sounding board of the pulpit are late-nineteenth-century replacements. New research shows that Burnet also executed the flowers in the soffit that surrounds the crest of the cove ceiling and the central pendant from which a London brass chandelier of 1803 is suspended. Anthony Forehand carved the large column capital of the chancel; English carver John Lord completed the altar. Most of this work was destroyed by Federal shelling in 1865, but the English wrought- iron altar rail, installed in 1772,

survives and has been restored with Prussian blue paint and gilded components. The present chancel area was restored after the Civil War with plaster details and the insertion of a Tiffany stained glass window after Raphael’s painting of St. Michael slaying the dragon. In 1906 Tiffany and Company was further engaged to enhance the chancel with the eight small plaster columns around the stained glass window and elaborate paintwork, especially the stenciled decoration in the apse. Further work was completed in this area by architect Albert Simons in the 1940s.

The box pews in the church are original and, like the columns, gallery facings, and soffits, are fashioned of red cedar. These have been restored with a vermilion wash, and the early-nineteenth-century pew numbers have been conserved. The noteworthy furnishings of the church include the 1770s font, ordered from London; the original case of the former 1768 Snetzler organ; and many marble memorial plaques, including one carved in London to Mary Blacklock located in the narthex under the steeple. In the surrounding burial ground, approached from Meeting Street through gates with funerary urns in wrought iron, is located one of the only in situ wooden grave boards in America, dated 1772. Also located here are gravestones for Edward Rutledge, signer of the Declaration of Independence; Charles Cotesworth Pinckney, signer of the U.S. Constitution; Gen. Mordecai Gist, Maryland Revolutionary War hero; and the Charleston jurist James Louis Petigru.

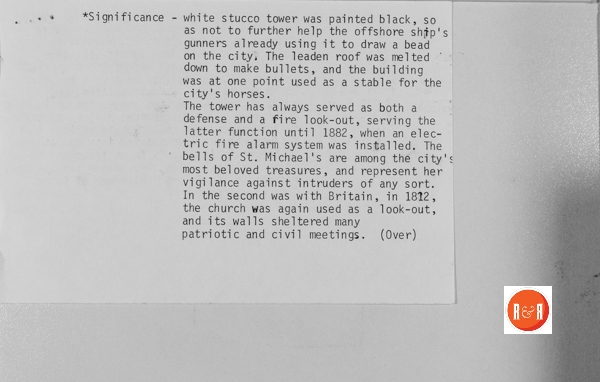

The church received shell damage to the chancel in the Civil War, but its steeple, painted black for the duration of the conflict, escaped damage. The bells, imported from England in 1764, were stolen by the British in 1782 and later returned. They were burned in Columbia in 1865 and returned to the Whitechapel Foundry of their origin to be recast. In 1993 they were again returned to Whitechapel and have been rehung as a full ring of bells. St. Michael’s Church is one of Charleston’s most enduring symbols. Often depicted by artists and described by writers, its bells are featured in the musical score of the opera Porgy and Bess.”

Information from: The Buildings of Charleston – J.H. Poston for the Historic Charleston Foundation, 1997

Click here for added information or for Beesley’s 1908 Guide of the Church.

Other sources: Charleston Tax Payers of Charleston, SC in 1860-61, Dwelling Houses of Charleston by Alice R.H. Smith – 1917, Charleston 1861 Census Schedule, and a 1872 Bird’s Eye View of Charleston, S.C. The Hist. Charleston Foundation may also have additional data at: Past Perfect

Stay Connected

Explore history, houses, and stories across S.C. Your membership provides you with updates on regional topics, information on historic research, preservation, and monthly feature articles. But remember R&R wants to hear from you and assist in preserving your own family genealogy and memorabilia.

Visit the Southern Queries – Forum to receive assistance in answering questions, discuss genealogy, and enjoy exploring preservation topics with other members. Also listed are several history and genealogical researchers for hire.

User comments welcome — post at the bottom of this page.

Please enjoy this structure and all those listed in Roots and Recall. But remember each is private property. So view them from a distance or from a public area such as the sidewalk or public road.

Do you have information to share and preserve? Family, school, church, or other older photos and stories are welcome. Send them digitally through the “Share Your Story” link, so they too might be posted on Roots and Recall.

Thanks!

IMAGE GALLERY via photographer Bill Segars – 2005

User comments always welcome - please post at the bottom of this page.

Share Your Comments & Feedback: