In 1929 the novel Scarlet Sister Mary by Julia Peterkin was awarded the Pulitzer Prize as the best American novel of the year. Mrs. Peterkin wrote several other novels and short stories with Low-Country settings. A native South Carolinian, she lived at Lang Synge Plantation near Fort Motte…..

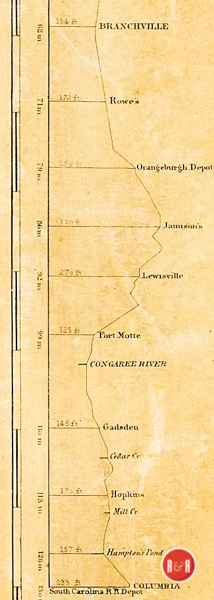

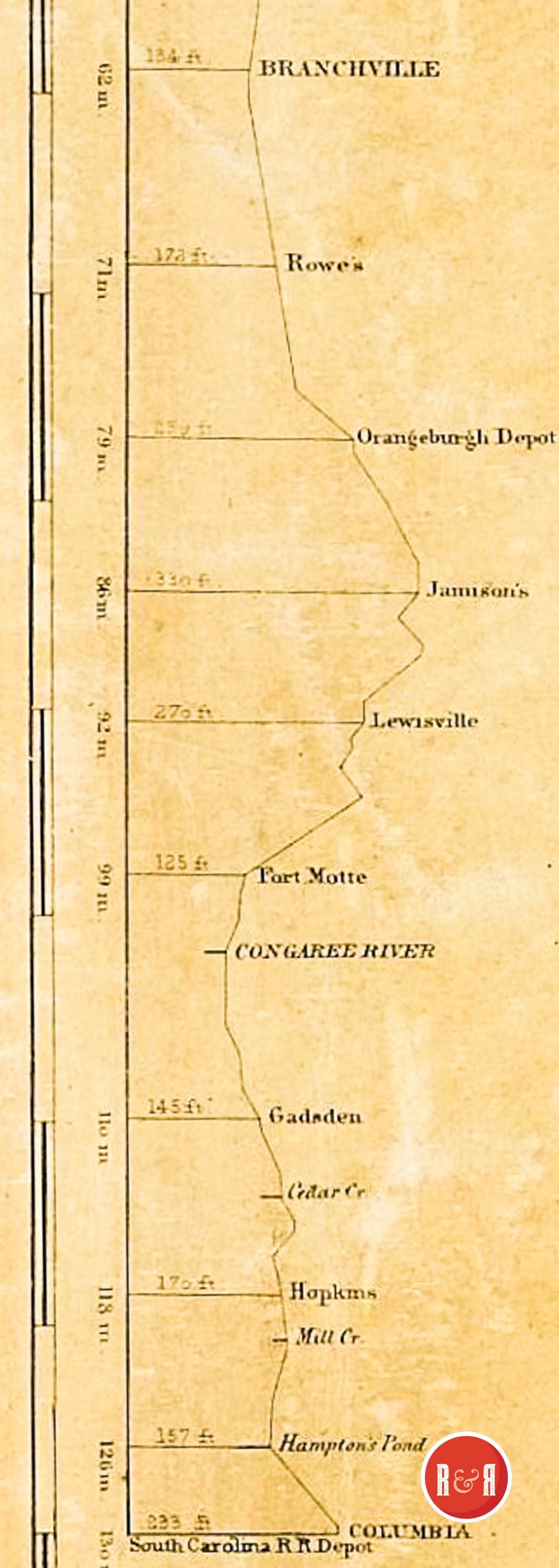

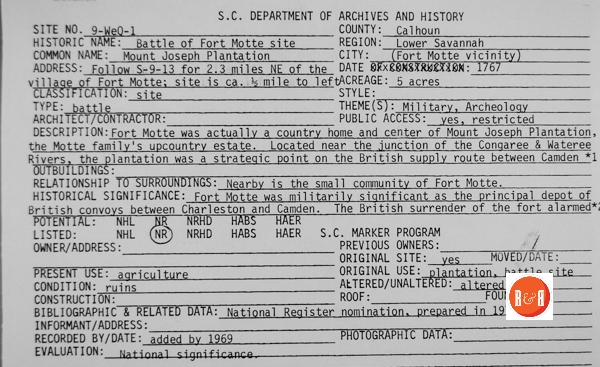

City Directories and History: (Mt. Joseph Plantation) Fort Motte was militarily significant as the principal depot of British convoys between Charleston and Camden during the American Revolution. Built in 1767, Fort Motte was actually a country farm and the center of Mount Joseph Plantation, the Motte family’s up-country estate. Located near the junction of the Congaree and Wateree Rivers, the plantation was a strategic point on the British supply route between Camden and Charleston. The fort was described as a “new mansion house…situated on a high

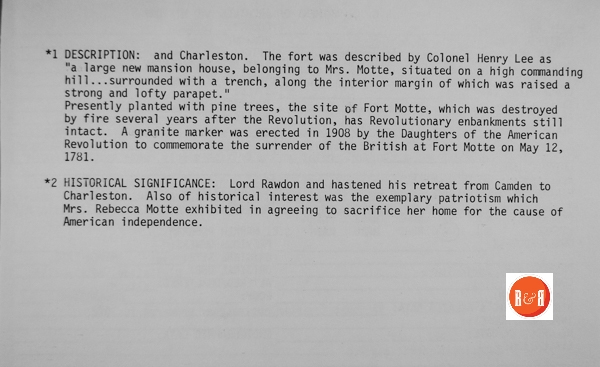

commanding hill…surrounded with a trench.” General Francis Marion and Colonel Henry Lee ordered the fort be burned and fired upon the British, and consequently, Captain McPherson surrendered. The British surrender of the fort alarmed Lord Rawdon and hastened his retreat from Camden to Charleston. Also of historical interest was the exemplary patriotism that Mrs. Rebecca Motte exhibited in agreeing to sacrifice her home for the cause of American independence. Rebecca Motte’s brother, Miles Brewton, gave her the East Indian arrows designed to ignite upon impact that she provided to Marion and Lee in order to force the British troops to surrender the fort and battlefield. In turning over these arrows, Rebecca Motte sacrificed her own home, and thus the fort burned causing the British to surrender. Listed in the National Register November 9, 1972.

commanding hill…surrounded with a trench.” General Francis Marion and Colonel Henry Lee ordered the fort be burned and fired upon the British, and consequently, Captain McPherson surrendered. The British surrender of the fort alarmed Lord Rawdon and hastened his retreat from Camden to Charleston. Also of historical interest was the exemplary patriotism that Mrs. Rebecca Motte exhibited in agreeing to sacrifice her home for the cause of American independence. Rebecca Motte’s brother, Miles Brewton, gave her the East Indian arrows designed to ignite upon impact that she provided to Marion and Lee in order to force the British troops to surrender the fort and battlefield. In turning over these arrows, Rebecca Motte sacrificed her own home, and thus the fort burned causing the British to surrender. Listed in the National Register November 9, 1972.

Click here for the National Register site.

Carolina planters were a small and close-knit society. In 1779, Eliza’s son, then Major Thomas Pinckney, married Elizabeth Motte, the daughter of long-standing family friends. Chief Justice Pinckney had been taken to Jacob Motte’s house in Mount Pleasant when he was stricken with malaria; he died in Motte’s home. The Mottes had a plantation in Santee near Harriott Pinckney Horry’s. Like the Pinckneys,the Mottes supported the colonial side. Mrs. Motte was the daughter of Robert Brewton, a prominent member of Charles Town society. She married Jacob Motte in 1758; the couple had three daughters and lived a privileged life until the outbreak of the Revolution.

- Photo Gallery of additional images contributed to R&R by Gazie Nagle @ www.fineartbygazie.com

Mrs. Motte’s brother was Miles Brewton, a well to do Charleston, S.C. merchant who fervently supported the colonial cause. He entertained lavishly before the hostilities began. In 1775, he was elected to the second Provincial Congress and set sail for Philadelphia. Brewton was accompanied by his wife and three children, whom lie planned to send to England. When their ship was lost at sea, Rebecca inherited his handsome brick home on lower King Street and Mount Joseph, a plantation near Orangeburg, where she built a mansion similar to her brother’s home in Charles Town.

Old store at Fort Motte. Image courtesy of photographer Ann L. Helms – 2018

Jacob Motte spent much of his fortune providing for the colonial army. He died in 1780, a few months before Sir Henry Clinton took Charles Town. Clinton made Miles Brewton’s mansion his headquarters, as did Lord Rawdon after him. Rebecca Motte was obliged to play “hostess” to her unwanted “guests,” who took over her home and forced her to move into cramped quarters. She prudently locked her three young daughters away from the British of officers. Hiding in the garret, they were guarded by a “mama” who smuggled food to them. Downstairs, Mrs. Motte entertained thirty British officers at her table daily. Lord Rawdon, whose reputation with the ladies was none tiie best, apparently knew of the duplicity, for when he left her home, he was said to have looked up at the ceiling and remarked that he regretted he had not had the opportunity to meet the rest of her family.”

When Rawdon permitted the Motte women to leave the city, they went to Mount Joseph plantation, located

Fort Motte Crossing: Courtesy of S.C. photographer Ann L. Helms – 2018

where the Congaree and Wateree Rivers merge to form the Santee. Due to its strategic location, the British decided to establish a post there and make it the major convoy depot between Charles Town and the interior of the state. They evicted the Motte ladies and fortified the house.The new garrison was named Fort Motte; it was manned by British infantry under the command of Lieutenant Colonel Donald McPherson. Once again, the ladies were forced into smaller quarters and removed themselves to a small farmhouse on the hill opposite the new fort.

General Nathanael Greene had been sent to command the southern army, and he brought “Lighthorse” Harry Lee and his cavalry with him. After Greene’s defeat at Hobkirk’s Hill near Camden in April 1781, Colonel Lee and General Francis Marion laid siege to Fort Motte. They arrived on May 8, and Lee set up headquarters at the farmhouse occupied by the Motte women. Marion commanded the ridge of the hill about four hundred yards from where the mansion stood. The 150 British troops were outnumbered. Marion had 150 men, and Lee had 300 Regulars and 150 North Carolina Continentals. On May 10, the Americans demanded that the British surrender the fort. McPherson refused. That evening, Marion and Lee learned that Lord Rawdon had decided to withdraw his forces from Camden and was heading toward Fort Motte. Emboldened by beacon fires announcing Rawdon’s approach, on May 11 the British again refused to leave the house. Lee realized that the only way to secure the fort quickly was to burn the British out. He reluctantly informed Rebecca Motte of this necessity. She immediately agreed to the destruction, and tradition states that she produced from the top of an old wardrobe a quiver of incendiary East Indian arrows that had been given to her brother Miles Brewton years before.

By noon of May 12, the trenches dug by Marion’s men were near enough to the house to enable Nathan Savage, a sharpshooter from Marion’s brigade, to fire flaming arrows onto the shingle roof. (According to another account, the roof was set alight by a ball of rosin and brimstone thrown by a sling.)

The British soldiers tried to extinguish the flames, but a six-pounder fired at them whenever they appeared. In a few moments, the white flag was hung out. Marion accepted the surrender; then both sides joined in putting out the fire. Restored to her handsome home, Mrs. Motte invited the officers of both sides to dine at her table, where she is said to have received all with equal courtesy.

After the war, Rebecca Motte returned to Charleston and sold her King Street house to her son-in-law, Captain William Alston of the Waccamaw Company of Marion’s brigade.'” Against the advice of her friends, she purchased valuable swamp land on credit and moved to the country. Her determination built up a successful rice plantation that enabled her to pay off her husband’s debts in full. She died in 1815, leaving her children not only a valuable unencumbered estate but also a rich heritage of patriotism and honorable deportment.” (The above information on Rebecca Motte was taken from Hidden Charleston History, courtesy and with full permission for use by author and historian, Peg R. Eastman.)

Stay Connected

Explore history, houses, and stories across S.C. Your membership provides you with updates on regional topics, information on historic research, preservation, and monthly feature articles. But remember R&R wants to hear from you and assist in preserving your own family genealogy and memorabilia.

Visit the Southern Queries – Forum to receive assistance in answering questions, discuss genealogy, and enjoy exploring preservation topics with other members. Also listed are several history and genealogical researchers for hire.

User comments welcome — post at the bottom of this page.

Please enjoy this structure and all those listed in Roots and Recall. But remember each is private property. So view them from a distance or from a public area such as the sidewalk or public road.

Do you have information to share and preserve? Family, school, church, or other older photos and stories are welcome. Send them digitally through the “Share Your Story” link, so they too might be posted on Roots and Recall.

Thanks!

User comments always welcome - please post at the bottom of this page.

[…] Fort Motte […]