As the county marched through the end of the 1800s it was in the midst of a most violent era that began around 1776. In fact, much of the South was struggling with inner violence. These teen years of the nation would eventually gave way to a more civil life as a social structure developed through a better standard of living.

In South Carolina, violence continued because of a weak judicial system, as well as the state’s hesitance in passing stringent laws on concealed weapons. As early as 1880, Circuit Judge Thomas J. Mackey blamed the rise in violent crimes on the lethal

Image ca. 1912 – Courtesy of the YC Historical Society

combination of guns and whiskey. York County court records confirm the judge’s premise, but public outcries for prohibition and gun control went unheard, and violent crimes prevailed. That same year, the state enacted a ban on concealed weapons of any kind, but this law was simply ignored, and during June of 1885, Judge I. Dommon Witherspoon addressed the York County Grand Jury lamenting that the laws dealing with concealed weapons were being violated with impunity.

Physical confrontations were not the only kind of attacks taking place in York County at the time, as Dr. Joseph G. Black of Blacksburg learned in the elections of 1884. In preparation for the Democratic primary to be held August 25, Democrats met in convention at Allison’s Hall in Yorkville on June 19 to elect delegates to the state convention to be held the following week in the House of Representatives. By the following month, southern Democrats were looking for a grand victory in September with the election of Grover Cleveland as president and Thomas A. Hendricks as his vice president.

On the home front, county Democrats were expecting to sweep the county and state as they had since Wade Hampton broke the back of the Republican Party in 1876. Dr. Black was a member of the executive committee as well as a primary candidate for the South Carolina Senate, opposed by Major James F. Hart, General Evader M. Law, and A. C. Spencer.

Toward the end of June, it was reported that the Yorkville town council had decided to investigate the indiscriminate sale of liquor by way of physician prescriptions. The wardens, or councilmen, of the town divided into teams and visited the town’s drugstores to examine the prescription sales of liquor. They found one case that was in violation of the law — three prescriptions of one quart each by a visiting physician attending to a delegate to the Democratic convention. The council decided to prosecute the physician, but for reasons unknown, they chose not to make their decision public and to defer the warrant.

When the county Democratic convention convened in July, W. R. Lipscomb shocked Black when he presented a petition asking for Black’s resignation, charging he had been “careless and indifferent to his duties” as an executive committeeman and had “worked and voted against Democrat nominees.” The petition — signed by D. D. Gaston, W. R. Lipscomb, and W. J. McGill — requested J. Augustus Deal to replace Black.

Black rose and addressed the convention, denying the allegations, saying it was the work of his enemies who had circulated it without his knowledge. The executive committee, chaired by Sheriff R. H. Glenn, formed a committee of three — Dr. W. G. Campbell, Iredell Jones, and John L. Rainey — to investigate the charges. They retired to collect statements from both sides, but time didn’t permit them to report their findings, and it was recommitted to a committee of five — J. C. Chambers, J. D. Hamilton, W. D. Camp, J. H. Barron, and J. C. McGill.

At least 17 Western York County men came forward saying that they had signed the petition to replace Black with Dill because they understood that Black had chosen not to serve, but they had no question about the physician’s character or his loyalty. Jonathan Moore and three others charged that their names were forged on the petition without their knowledge. And 116 voters submitted a letter to R. H. Glenn, chairman of the county Democratic executive committee, saying the petition was “conceived in personal ill feeling” and that the doctor should be retained on the committee and no investigating committee was necessary. Black retained his seat.

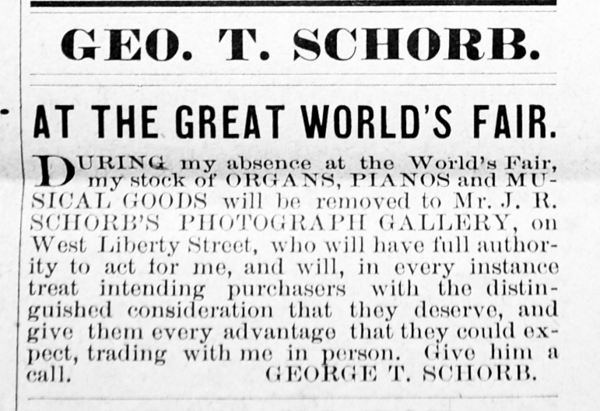

Succeeding in keeping his character intact and retaining his seat on the executive committee, it seemed it would be smooth sailing for Black through the election, but the unexpected happened on August 7. The mayor of Yorkville, George W. S. Hart, and his councilmen — E. B. McClain, John R. Schorb, W. H. Herndon, and John R. Ashe — announced that they would be prosecuting Dr. Black for unlawfully giving prescriptions of liquor. The town alleged that on June 21 Black came into town and found five people wanting prescriptions of whiskey to relieve ailments. What made the situation strange was that they needed whiskey and no other medication — two needed one quart each, one needed three quarts, and two needed two pints each.

The mayor and councilmen met soon after they had knowledge of the crime, and while the council wanted to issue a warrant for Black’s arrest, they agreed to wait until the day of the upcoming election. None of the men had any inkling that the doctor was considering becoming a senatorial candidate. The council met again on July 21, and just before they began, Mayor Hart stopped in at the Yorkville Enquirer office to see if the announcement about Dr. Black would be in that week’s issue. He was informed that the manuscript had not been received. When he met with the council, he withdrew his request to make a public announcement and applied for a warrant.

Hearing that the council was going to prosecute, some believed the council’s decision was politically motivated to injure the doctor’s chance of being elected. When the rumor reached the mayor’s ear he responded by saying that neither he nor the council were going out of their way to correct the lies being told by the doctor’s friends but that they were unwilling to remain silent. He said that a sense of duty was the only thing that motivated the council, and it stemmed from the fact that for the privilege of not having liquor sold within the town limits, it cost the people $800 in taxes.

Apparently pressured by the public, the mayor and council began backing off. In their statement to the press, they acknowledged that, “the council may have erred in regarding Dr. Black in common with other physicians, as amenable to that law which says, ‘It shall be unlawful for any physician to give a prescription for any such liquors except when actually in bona fide attendance upon a patient.”

The election primary went off as scheduled on August 25, and the count showed Black had won, but the executive committee was notified that a second count of the Blacksburg ballots would be necessary since a protest would be lodged, alleging corrupt voting. A committee to recount the votes consisted of Iredell Jones, Dr. J. E. Massey, Dr. W. G. Campbell, W. B. McCaw, and John L. Rainey. The recount results were Black — 271, Spencer — 31, Hart — 12, and Law — 15.

Although all but two ballots were deemed legal by the committee and the number of votes agreed with the poll list, letters of protest were submitted to the executive committee by all three of Black’s opponents. General Law contended that the Blacksburg precinct had never had more than 189 voters, and he charged that at least 34 Republicans had voted at the Blacksburg precinct. Lipscomb said that he had knowledge that well-known Republican supporters were not questioned at the Bethany Precinct and that two non-residents had voted at the Bullock’s Creek precinct. Hart went a step further than his fellow complainers, wanting the executive committee to pronounce the election to be null and void because of irregularities and fraud. Perhaps in retaliation or to show that his opponents were not lily-white in their dealings, he declared that he was ready to prove an un-paroled convict voted for Spencer at the Yorkville precinct. The committee adopted a resolution to investigate any irregularities, and Chairman Glenn ordered all to come before the committee on the 27th with evidence in hand.

As soon as the count came in and he heard the election would be contested, Spencer considered withdrawing from the Senatorial race, believing he would be inconsistent in his thinking if he contested the election and remained a candidate. Both Major Hart and General Law strongly urged him to reconsider, since they believed the committee would pronounce the election null and void, but when the committee convened on August 27, Spencer petitioned them to strike his name as a candidate and relieve him from taking any part in the investigation.

Iredell Jones moved that the committee proceed to canvas the vote for senator and hear any protests and evidence that might be presented. The motion was seconded and adopted. Blacksburg, the first precinct on the list, was called, and the results were announced. The precincts of Bullock’s Creek and Bethany were next on the list. Testimony from a large number of witnesses concluded about 2:00pm on Thursday, August 28.

Irregularities were found to exist at only the three precincts in question — Blacksburg, Bullock’s Creek, and Bethany. Committeeman Chambers moved that the committee declare the election on the face of the returns. It was seconded by Jones but was rejected by a vote of 8 to 7.

Dr. Campbell then moved “that upon the evidence heard from the Black’s Station [Blacksburg] precinct by the Executive Committee of York County, that we now declare the election for Senator null and void, and that a new election be ordered.” The motion was seconded by Rainey and passed unanimously.

Committeeman Black, candidate for state senator, asked permission to speak to the committee. “Gentlemen, at the primary election held on the 25th instant, for Senator and other officers, I, as a candidate for the State Senate, received a plurality of the votes given.

“There is no possible doubt, in my opinion, that the result as announced by the returns, was as fair as is possible to be obtained in a contest of this exciting character. Neither myself nor my friends can admit for a moment any other proposition.

“But from the closeness of the contest, some dissatisfaction may arise and some men’s minds may be divided upon the question of the result. The question is not so much, who shall be the nominee of the party for this high office, as that other high question, the preservation of the unity and harmony of the Democratic Party of York County, especially upon the eve of the approaching national election.

“Sincerely impressed with the conviction that the latter proposition is paramount to all mere personal or selfish considerations, I have, after due reflection, decided to submit to your honorable body the propriety of ordering another election, at some early day, for State Senator; and I here announce myself, if you accept my proposition, as a candidate for the nomination to that office.

“I might have submitted this proposition at an earlier moment, but for that reluctance I felt that such a course might place my friends, who so cordially supported me, in a false position as regarded their fairness and integrity of conduct, and but for the desire to the fullest investigation of the management of the election.”

Secretary W. B. McCaw moved that another election for senator be held on Thursday, September 11, 1884. The motion was seconded and unanimously adopted. A resolution was adopted, directing the precinct managers to make their returns to the executive committee at 12:00 midnight, on Friday, September 12th, 1884.

The following week, Black, Gaston, and Lipscomb communicated with each other and the public through “cards” printed in the Yorkville Enquirer. Black denied all allegations, while Gaston and Lipscomb contended that they had no ill feeling when filing their petitions, insisting they did so in the best interest of the party. To add weight to their charges against Black, the two declared that they had 22 signers who were ready to stand behind the charges and with little effort could get many more who would testify under oath.

On September 4 a card from Dr. Black appeared in the newspaper with the purpose of correcting “some misapprehensions in regard to the strength of the Democratic vote at Black’s Station.” “I refer the public to the returns from that precinct in the election of 1876 when I. D. Witherspoon received 321 Democratic votes and Hannibal White 78 votes for the Senate. This shows a total vote of 390 votes cast there in 1876, since which the village has grown up with a population of 420 souls and a voting strength of 83 votes. There are about 90 Negro voters within the bounds of Black’s Station precinct and 35 to 40 can always be depended upon to vote the Democratic ticket in any emergency. The managers of election at the recent primary election at Black’s Station precinct are honorable and high toned men, and incapable of fraud or of permitting fraud to be committed in the election. The contest of Black’s Station vote was conceived in personal spite toward me on the part of W. Anderson and W. R. Lipscomb.” A week later, Anderson and Lipscomb responded, protesting Black’s “unjust attack” upon them.

Regarding their support for Spencer, they said the protest was not done with spite but that they had simply come to the support of their friend, whom they had supported before the investigation by the executive committee. By the end of the month, the two factions were exchanging angry words through the Yorkville Enquirer.

Three days before the election, a “bombshell” fell on the county in the form of a handbill authored by “Fair Play.” These were distributed among the voters and published in the Enquirer, addressed to “The Democracy of York.” It read, “On Monday last, the County Executive Committee for York County met at Yorkville. A petition was presented from a Spencer Club, asking the committee to change the rules under which the previous primary election was held, so as to exclude all persons from voting at the election on the 11th instant, who had not registered. The committee, by a vote of 8 to 6 so amended the rules.

“The avowed object of this petition was to exclude from the support of Dr. Black, the largest vote he had previously obtained in localities remote from the Court House, where voters had not the same facilities for registering as near the center.

“When Dr. Black surrendered his former plurality and proposed a new election in the interest of harmony, neither himself nor his friends supposed that new conditions would be imposed three days before the election, calculated to secure his defeat. The voters of York County will no doubt resent this action in the proper manner. It is now too late for any unrequited friends who previously voted for him to register. Let them go to the polls and have their places supplied by registered voters.”

The Executive Committee was concerned that the handbill, distributed at some of the precincts, might mislead voters. They were incensed that it grossly misrepresented the committee. Secretary W. B. McCaw issued the following statement. “On Monday last, the Executive Committee met at Yorkville and a petition was presented to them by the Spencer Club of Rock Hill asking that the committee construe rule 5 of the rules for conducting the primary elections of York County. The petition did not ask, as is alleged by “Fair Play” that the committee change the rules under which the previous primary election had been held, but simply asked a construction of an existing rule, to wit: ‘All persons known to be in full sympathy with the Democratic Party, who will be entitled to vote at the ensuing general election shall be entitled to vote at the primary election.’

“The committee, by resolutions, construed the said rule to mean that only those persons who bear the general reputation of Democrats in the neighborhoods in which they live are entitled to vote in the primary elections, and that all non-residents, all persons convicted of any of the disqualifying crimes against the peace and dignity of the State, and all persons who have failed or refused to take out registration certificates, except those persons known to be Democrats, who are to become of age before the day of the general election, and provide themselves with registration certificates are disqualified to vote in the primary elections.

“The above resolution was passed, not as is alleged by “Fair Play” by a vote of 8 to 6, but by 8 to 3, and one of these three voting with the minority, promptly moved that the resolution be made unanimous. In thus construing rule 5, the committee did not change the rule, but simply made clearer what was already clear upon the face of the rule itself. Neither did they manufacture any new law imposing new conditions, but simply gave utterance to the State law governing general elections as it is set forth in Sections 89, 90 and 97 of the Revised Statutes of South Carolina.

“Rule 9, for conducting the primaries, provides that the State law governing general elections shall apply in all cases not covered by the prescribed rules for conducting the primary elections. Respectfully, W. B. McCaw.”

After the election result was declared, the executive committee began its investigation of who authored the inflammatory circular by asking each member to furnish any information he might have. Though some had seen the handbill, none had an idea who was responsible. But when Dr. Black was questioned, he gave evasive answers and seemed unwilling to cooperate. He admitted that he had seen the circular and had even distributed a number of copies but declared that he knew nothing else. It was decided to seek information from Lewis Grist, the editor of the Yorkville Enquirer.

Grist agreed to give the committee whatever information he knew but would do so only if the committee voted on the request. After the motion was made, seconded, and adopted, the editor said that Black came to his office on the 10th, asking him to print 1,000 copies of “Fair Play.” Grist said that it was Black who had furnished the manuscript. Later in the day, he turned the copies over to a man who came to the office, saying that Black had authorized him. In the afternoon a second lot was handed over to the man, and the remainder was delivered to Mr. Holler.

A member of the committee reported that he had knowledge of a rumor that “Fair Play” was authored by Major Hart. When a three-member team — Campbell, Chambers, and Leander Adams — went to interview Hart, they were told that he was, indeed, the author and that the views expressed in the circular were his own. Summoned to meet with the executive committee, he mentioned that the rules for conducting primary elections were adopted in 1880, that three primaries and one special election had been conducted under those rules, and not once had they been construed to exclude unregistered voters if they were Democrats.

If the rule was correct, he contended, the election was illegal because both registered and unregistered Democrats made those nominations. He informed the committee that when they met three days before the election and accepted a petition by the friends of one of the candidates, in effect they made a new rule. While this might have been legal, he argued that it should have been published before the registration books were closed. Though he believed the committee had erred, he did not mean it to reflect on the motives of the committee, but as far as the circular was concerned, he offered no apology or retraction.

How was it that Black was involved? It was written by a friend of Dr. Black and given to him to use as he chose. It was resolved by the committee that since Secretary McCaw had already replied in defense of the committee and that they were in full agreement with “every statement,” no further action would be taken.

John Gillard Black, M.D., was born July 17, 1842 and was the son of William C. and Jane Logan Black. He attended the South Carolina College until he enlisted into the Confederate Army, serving as Quartermaster Sergeant. He graduated from the Medical College of South Carolina on March 13, 1868. Dr. Black served in the state House of Representatives from 1880 to 1882. Elected to the Senate in 1884, he took the seat of James F. Hart, who had served from 1882 to his defeat in 1884. Black served in the state Senate until 1888. Hart’s son, John Ratchford Hart, served in the South Carolina House of Representative from 1918 to 1920 and was elected to the state Senate to fill the term of 1920-1924.

Politics has always been a contact sport.

J.L. West – Author

This article and many others found on the pages of Roots and Recall, were written by author J.L. West, for the YC Magazine and have been reprinted on R&R, with full permission – not for distribution or reprint!

Stay Connected

Explore history, houses, and stories across S.C. Your membership provides you with updates on regional topics, information on historic research, preservation, and monthly feature articles. But remember R&R wants to hear from you and assist in preserving your own family genealogy and memorabilia.

Visit the Southern Queries – Forum to receive assistance in answering questions, discuss genealogy, and enjoy exploring preservation topics with other members. Also listed are several history and genealogical researchers for hire.

User comments welcome — post at the bottom of this page.

Please enjoy this structure and all those listed in Roots and Recall. But remember each is private property. So view them from a distance or from a public area such as the sidewalk or public road.

Do you have information to share and preserve? Family, school, church, or other older photos and stories are welcome. Send them digitally through the “Share Your Story” link, so they too might be posted on Roots and Recall.

Thanks!

User comments always welcome - please post at the bottom of this page.

Share Your Comments & Feedback: