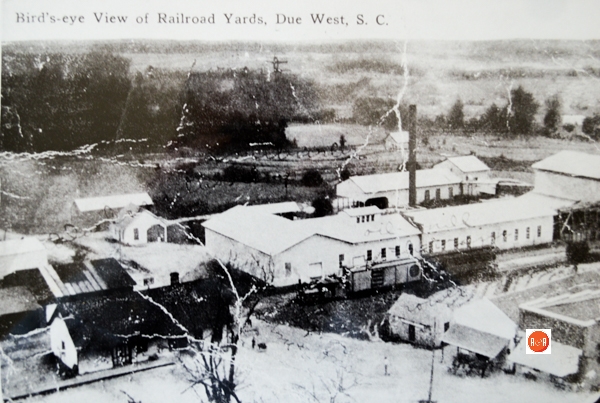

City Directories and History: By far the largest commercial venture in Due West history was the Due West Oil Mill, begun in 1909 by Roddey Stevenson Ellis, Sr. The raw material, cotton, was processed in a gin and the cotton seeds moved through a series of buildings as it was rendered into oil, meal and hulls.

Mules and wagons arrived in Due West from all directions and from miles around. The wagons lined up and moved to the gin building where the cotton was put into a fourteen-shelf dryer operated by a twenty horsepower electric motor. Next lint cleaners operated by another electric motor removed leaves, sticks and other debris. The product then entered a gin powered by a one hundred horsepower electric motor. The gin de-seeded the cotton, cottonseeds dropped below and a conveyer took them to the top of the building. The cotton passed through another lint cleaner and on to the pressroom where it was compressed into bales of cotton and was ready for shipment. Cotton brokers purchased the bales, stored them in warehouses or shipped them out immediately.

At conveyor at the top of the gin building transported cottonseed about thirty yards to a building containing a de-linter room and storage bins. This building sat along the railroad, the first of a range of buildings with loading docks constructed parallel to the rails. A system of conveyors distributed cottonseeds to bins on the second and third floors of the building. The cottonseed was either shipped on the railroad or stored for processing. Processing continued with a conveyor moving cottonseeds to the next building where lint was removed in the linter room. The seeds to be processed were transported via the conveyer system through the power building to the pressing building. After the advent of electricity the press was operated with electric motors and was housed in the last building that sat along the railroad with its outer wall next to Depot Street. The initial electric motor required a 550-volt current but later that motor was replaced with a modern 440-volt motor. After the facility no longer pressed cottonseeds fertilizer was stored in this building until the late twentieth century. Declining demand for fertilizer did not justify needed repairs so the building was torn down in 2006.

Before electricity there was a brick structure between the linter room and the pressing building with firewalls on the three internal sides. On the external side, that opposite the railroad, there was an opening through which coal was inserted for the boiler. The boiler providing the seam power used to press out the cottonseed oil. In first three decades of the century a steam whistle blew at 7:00 a.m. to mark the beginning of the workday. It blew at noon to signify lunch time and again at 6:00 p.m. to end the workday. These long hours were necessary to process the cotton that continuously arrived in mule drawn wagons or later trucks. Such long hours are unimaginable in the twenty-first century but in the first half of the twentieth century there were countless potential workers waiting for a chance to work those hours for two dollars a day.

Whether the power source was coal or electricity, the presses cooked and squeezed heated cottonseeds into cottonseed oil, meal and hulls. The meal and hulls were sold as animal feed. The meal had a 36% protein content and was valuable, usually scattered over the hulls to be consumed by hogs, cattle or other animals. There were many uses for the oil.

The Oil Mill also sold fertilizer and coal since it maintained a large amount of that fuel for power. The fertilizer was delivered by rail until 1939 and sold to farmers in bags or bulk for cotton and other crops. After their development specialized trucks hauled and distributed the fertilizer on pastures across multiple counties in South Carolina or across the Savannah River in Georgia. This enterprise employed a strong workforce and spawned other business. It was a perfect companion enterprise because the workers who processed cotton could be retained during the months before and after the cotton harvest.

The cotton gin was the second one in Due West. An earlier one was smaller and built before the railroad. It was located on property now owned by Renaissance and Mr. Danny Ware, above the crossroads formed by Highway 184 (Main Street) and Highway 185/20 (the highway to Anderson).

In the middle of the complex of buildings stood three tanks. Two were storage tanks for the cottonseed oil and the third held water used by the steam engine in the early years and later by the ice plant.

In 2015 one may stand by the Oil Mill office and look across the empty space where the complex of buildings stood. Beyond where buildings once stood is the electrical supply station for the town of Due West. This station was originated to supply power for the Oil Mill. Before the Oil Mill demanded a major improvement in the electricity available, a much smaller electrical supply station was located in a tin building at the corner of Dode Phillips and Young Streets (near the corner of the Robert Stone Galloway Physical Activities Building of Erskine College).

The Due West Oil Mill office was replaced in the 1990s by a replica used until the Oil Mill closed. An eighteen-wheeled truck filled with nitrogen fertilizer rolled down the hill into the original office. The new office is located, as was the old office, with the weighing scales pad on the side opposite Depot Street. Wagons or trucks would pull up to the window above the scales to be weighed. Vehicles would be weighed empty, and filled to determine the weight of the cargo.

Below the Oil Mill complex on the same side of Depot Street is a large building housing Erskine College’s building and grounds’ facilities. That building was the location of a clothing manufacturing business from the decade before World War II until the decade after that conflict. The company employed females, the only facility within ten or twelve miles where women could find employment. It was known as the “Shirt Plant” because its primary product was shirts for men.

Sources: Lowry Ware, A Place Called Due West: The Home of Erskine College, 1997, pages 170-174. Interview with Roddey Stephenson Ellis, Jr. on January 2, 2008 (Contributed to R&R by James Gettys – 2015)

Stay Connected

Explore history, houses, and stories across S.C. Your membership provides you with updates on regional topics, information on historic research, preservation, and monthly feature articles. But remember R&R wants to hear from you and assist in preserving your own family genealogy and memorabilia.

Visit the Southern Queries – Forum to receive assistance in answering questions, discuss genealogy, and enjoy exploring preservation topics with other members. Also listed are several history and genealogical researchers for hire.

User comments welcome — post at the bottom of this page.

Please enjoy this structure and all those listed in Roots and Recall. But remember each is private property. So view them from a distance or from a public area such as the sidewalk or public road.

Do you have information to share and preserve? Family, school, church, or other older photos and stories are welcome. Send them digitally through the “Share Your Story” link, so they too might be posted on Roots and Recall.

Thanks!

User comments always welcome - please post at the bottom of this page.